Qualitative studies

← vista completaPublished on May 24, 2021 | http://doi.org/10.5867/medwave.2021.04.8186

A qualitative study on the elderly and mental health during the COVID-19 lockdown in Buenos Aires, Argentina - Part 1

Estudio cualitativo sobre los adultos mayores y la salud mental durante el confinamiento por COVID-19 en Buenos Aires, Argentina - parte 1

Abstract

Introduction On March 19, 2020, preventive and mandatory social isolation was decreed in Argentina in response to the pandemic caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus and the disease it causes (COVID-19). This measure aimed to reduce the transmission of the virus and the resulting severe respira-tory condition that frequently besets older adults. However, this measure can also affect the support networks of these isolated people.

Objectives To explore the emerging needs related to the mental health of isolated older adults in this period and to identify the main support networks they have and the emerging coping strategies in the face of the situation.

Methodology We carried out an exploratory qualitative study, summoning participants over 60 years of age. Using snowball sampling, a group of researchers contacted them by phone to collect data. The analysis of the findings was triangulated among researchers with different academic backgrounds (medicine, psychology, and sociology). The concepts emerging from the interviews were linked in conceptual networks using an inductive methodology and were mapped into conceptual frameworks available to researchers. Atlas.ti 8 software was used for coding.

Results Thirty-nine participants belonging to the Buenos Aires Metropolitan Area were interviewed between April and July 2020. For greater clarity, the main themes were described in five cross-sectional axes: network configurations, resources and coping strategies, affective states and emo-tions, perceptions and reflections on the future, and actions emerging from the participatory approach. Participants reported distress, anxiety, anger, uncertainty, exhaustion, and expressed fear of contagion from themselves and their loved ones. We identify greater vulnerability in people living alone, in small and closed environments, with weak linkages and networks, or limited access to technologies. We also found vari-ous coping strategies and technology was a fundamental factor in maintaining the bonds.

Conclusions The findings of this research have implications for decision-making at the individual level, health systems, professional care, and policy devel-opment. Future research may elucidate the regional, temporal, and socioeconomic variations of the phenomena explored in our research.

Main messages

- Social distancing and the different measures to avoid the contagion of coronavirus hurt older adult psychosocial well-being.

- In the mental health dimension, we identified that anguish and fear of contagion predominated, although fear decreased with successive extensions of the confinement.

- Technology was a key player in maintaining supporting networks and meeting emerging needs.

- These findings are limited to a telephone survey with a qualitative approach in a middle-class population of the Buenos Aires metropolitan area.

Introduction

The population of adults over 60 years of age is progressively increasing, such that by 2050 it is expected to globally escalate more than double (from 962 million in 2017 to 2.1 billion in 2050) [1]. In Argentina, there are currently more than 6.7 million people over 60 years of age, representing 14.27% of the total population [1], concentrated in urban centers, particularly in the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires, where the highest proportion of the entire country is concentrated (15.7%) [2],[3].

We are currently undergoing a pandemic caused by the new SARS-CoV-2 virus, whose spectrum of COVID-19 disease ranges from mild (in approximately 80% of cases) to respiratory failure and death [4]. As of November 3, 2020, it affected 1,027,598 people in our country, including 32,106 deaths. The mortality rate depends on multiple factors. However, the highest mortality is found in older adults, which reaches up to 20% according to some estimates [4],[5].

Lockdown of confirmed cases with other prevention and control measures (such as social distancing and the use of masks) has shown a greater effect in reducing new cases, transmissions, and deaths compared to individual measures [6]. The modalities of social distancing in the countries were diverse: in Spain, strict lockdown measures were maintained, while in the United States, social distancing measures were heterogeneously reinforced [7],[8]. On the other hand, Brazil rejected the social isolation measures adopted by the rest of the countries [9],[10]. In Argentina, on March 19, 2020, Social, Preventive and Mandatory Isolation (lockdown) was decreed [11] to reduce the displacement of individuals, the spread of the SARS-CoV-2 virus and to "flatten the curve" of cases. This period also sought to "buy time" to strengthen the operational capacity of health systems. Isolation measures were gradually relaxed until June when restrictions on movement were again introduced due to the increase in cases.

There are important differences between social distancing, which refers to avoiding groups of people and keeping two meters away from others as a strategy to reduce contagion [12], and social isolation, which refers to loneliness, that is, to an individual having an insufficient social support network, whether at the structural, functional and/or perceived level. In addition to having an independent predictive value on the survival of individuals, social isolation is related to morbidity and mortality through its influence on the other known risk factors. There is evidence that people in social isolation have more cardiovascular disease and depression [13],[14],[15], greater disability, poorer responses to illness, and earlier deaths [16],[17].

Strategies such as compulsory social distancing could have a strong psychosocial impact on older adults [18] by fostering the development of social isolation or deepening a preexisting one, which exposes them to a situation of greater psychosocial vulnerability.

The objective of our research was to explore the emerging needs of isolated older adults and identify the main support networks that older adults rely on during this period. We also set out to identify barriers to the effective implementation of preventive isolation and to design participatory resources that provide a space for support and telephone information for participants. This first part reports the results related to mental health needs, support networks, and participatory aspects of our research. In a second report, we will analyze the needs related to health care during isolation.

Methodology

We decided to carry out a qualitative research approach within the framework of the action research strategy, which allows the approach of a particular situation both in its understanding and its transformation. The epistemic framework is constructivist, where the space for dialogue and reflection among social actors is generated in such a way that it allows the construction of knowledge on the different problems that are revealed from their understanding and analysis of the particular situations in the singular context presented in the enforcement of the DNU 297/2020 for the elderly. Lewin conceived this design as a collective activity, as a social reflexive practice with the intention of bringing about appropriate changes in the situation under study [19],[20]. The decision to choose this action-research strategy is based on the link between the study of the problem and the social context that determines it to produce knowledge and generate social change [21].

Participants

We recruited adults over 60 years of age who live alone, or with a family member over 60 years of age, or with a family member within the risk groups for severe disease by COVID-19 (people with chronic heart or respiratory disease or immunosuppressed), or with a family member with a disability, who had access to a landline or cell phone, and reside in the metropolitan area (the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires and Greater Buenos Aires).

Field access techniques

Participants were selected by snowball sampling, contacting family members or friends who knew people who met the characteristics mentioned above and letting them know in advance that a researcher would call them. In turn, participants were asked to contact other people who could participate in the research with the same safeguards. A database was assembled with the telephone numbers of people eligible for the study, maximizing diversity in age, gender, educational level, cohabitation status, and locality. In addition, this tool was used for fieldwork planning and follow-up.

Intervention and data collection

The research team consisted of medical teachers (two family physicians and a sociologist), medical students, and a psychologist. An interview guide with open-ended questions was used to explore the primary and secondary objectives. Finally, reliable information from official media (national, provincial and the metropolitan area) on COVID-19 was offered. We collected notes and from the interviews and associated them to the telephone number of the database by adding the first name and locality of the interviewees in order to map the individuals and to be able to analyze possible containment strategies. In addition, we used virtual meetings as a space open to reflection, where we analyzed the different sensations and perceptions that we as researchers went through in the contact with the participants and their implication in the receptivity of the information. In this way, we used as a tool a "research diary" of each researcher to account for these reflections.

Analysis strategy

In qualitative analysis, the stages do not follow a sequence as is usually the case in a quantitative study but they are processes where interpersonal relationships and meanings feed the empirical corpus. An analysis that progresses in a spiral fashion is required, in which iterative work will be carried out, moving forward, backward, and revising the previous. The data obtained from the interviews was organized and classified into categories using an open coding system, which is a dynamic process. The steps for the analysis, in the manner of the researcher "bricoleur" in the words of Denzin [22],, were organized in three stages known as: 1) Reduction of data through coding, relationship of themes, classifications. 2) The presentation of data, exercising a reflective look in general, use of concept maps, diagrams and synopses. 3) The moment of conclusions is the most reflective moment. Following Taylor-Bogdan [23] in these three moments, which he calls discovery, codification, and relativization in parallel, the aim is to develop an in-depth understanding [24]. Within the framework of action research; analysis and reflection, while posed as moments in themselves or layers within the research process, are the constant within the modifying process of transformative action, beyond the crystallization of categories and conclusions or proposals.

The sample was intentional, significant, and relevant. The starting point was a system of codes rooted in the interview questions, allowing the entry of free codes and constant comparison. The Atlas.ti 8 software was used for coding. A data matrix was elaborated in a recurrent and circular process so that it could be broken down into a descriptive dimension of the analysis and subsequently interpretative. The analyses were triangulated between researchers with different academic backgrounds (medicine, psychology, and sociology) through virtual team meetings to share findings and review among those involved. The strength of this modality of qualitative analysis lies in the fact that it allows the generation of concepts and the development of theory based on empirical evidence and will allow the design of strategies based on the systematization of the data [25]. The results are reported following the best scientific practice in participatory action research [26] in executive summary format.

Ethical considerations

The objectives of the study were explained to those invited to participate, and they were informed of the characteristics of the study by telephone through a process of oral informed consent. The identity of the participants was protected in a password-protected database. The study was conducted in full compliance with international research ethics regulations. The protocol was evaluated and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Instituto Universitario Hospital Italiano (No. 0001-20).

Results

Characteristics of the participants

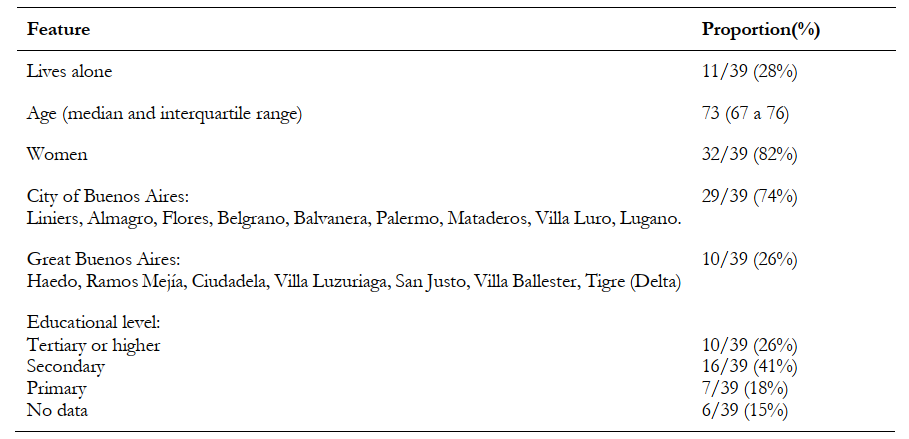

Thirty-nine participants from the metropolitan area of Buenos Aires were interviewed between April and July 2020. Although we did not formally identify the data, the participants were predominantly middle class. They had basic needs covered, were literate, and most had health coverage. The characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Full size

Full size The concepts emerging from the interviews were linked into conceptual networks using an inductive methodology, mapping to conceptual frameworks available to the researchers. For a clearer presentation, the main themes were described in five cross-cutting axes:

- Bonding configurations.

- Resources and coping strategies, including the use of technologies.

- Affective states and emotions.

- Perceptions and reflections on the future.

- Emerging actions of the participatory approach.

1. Bonding configurations

Bond configurations describe how a subject relates to a person, an object, an institution, or an ideal, and the impact that this bond has on his or her representations. The bond is inserted in an intersubjective space, characterized by its intimate bidirectionality, and its meaning comes from the relationship formed between the subject and the other, which, in turn, is formative of both [27]. We take this concept because of the importance of the bonds thought by Iacub as "material supports of identity", being that the changes that occur in the bonds that reconfigure "the representation of self" and its interaction with other people [27]. We organized into three groups based on the participants' statements: a) The family network; b) The network of friends, neighbors, and other peers; c) Perceptions of government policies and decisions.

1a. The family network

The participants identified immediate family members as the primary support and containment network, who would provide solutions to their emerging needs: relatives, children, and grandchildren were in charge of shopping or doing paperwork, allowing older adults to remain in their homes. On the other hand, some of the surveyed people looked for creative and novel ways to solve errands by their own means.

Family members were also a motivating figure since the activities that the older adults carried out for their families made them feel useful and occupied their free time. Some of these activities included: knitting coats for the grandchildren, cooking for the children, making handicrafts for their relatives, among others.

On the other hand, the vast majority of interviewees reported leaning on their cohabiting partner, reinventing their relationship, and enjoying each other's company by doing different activities together. However, in some situations, the problematic relationship of the participants with their partners worsened as a consequence of confinement, producing feelings of discomfort, repetitive arguments, and an environment that makes confinement difficult.

"I argue a lot with my husband, he doesn't help me at all and he knows I feel bad." Woman, 79 years old.

"It distresses me to live cooped up with my husband, all the ailments I have are because of him." Woman, 77 years old.

With the loss of the working routine, many of the interviewees devoted themselves to their families full time. The impossibility of being close quickly turned into a demand for physical contact and affectionate warmth. Thus, many opted to breach the mandatory isolation and even disregarded the distancing measures when seeing them, engaging in risky behaviors such as hugging and kissing without considering the consequences. In addition, participants expressed the fear of becoming a burden to their family and the self-perception of worthlessness that the situation generates for them.

"I feel like a coward for sending my wife to run errands". Male, 72 years old.

1b. The network of friends, neighbors, and other peers.

Regarding their peers, friends, and neighbors, they seem to be an additional support group for the population interviewed, in permanent contact in spaces where they share thematic areas of interest, recreational and informative activities, among others. If with the family at times they tend to feel a burden, with their peers they find a space where they can share and support each other, without perceiving themselves in this way.

"We made a chain with my friends, calling each other when we have important information to share, for example, one of them found out about a greengrocer who delivers to your home, you place your order and they deliver one day in each neighborhood". Woman, 87 years old.

It was mentioned Empathy was displayed among "those of their generation", with whom they felt understood because they share thoughts, interests and ways of life. These encounters would be favored through virtual communications mediated by digital platforms such as WhatsApp, Facebook or Zoom, which allow maintaining contact through calls or video calls. It seems important to us to mention that the vulnerability situation produced a positive effect that brought them closer to their friends in some cases. This generated a bond of mutual support.

"The fact of not being with their peers is going to make society very sick. I have a high school group on whatsapp, we share music, we share memories, and if I get down the other one lifts you up, or the other way around. The whatsapp group helps me a lot" Woman, 61 years old.

1c. Perceptions of government policies and decisions

Some participants reported being treated "like children" by the government and its actions. This aspect would seem to be linked to the concept of "state paternalism," understood as any paternalistic action carried out by a state organ and exercised on citizens [28].. This sentiment arises from recommendations by the government to keep especially older adults confined to their homes because they belong to the group with greater risk of presenting the most severe forms of COVID-19.

"I miss having more will and possibility to act, being locked up is bad, many things were handled in an arbitrary or authoritarian way. Old-ageism as a concept has already changed, although some people don't like it, underestimating the elderly, saying that we have to take more care of ourselves... the city government wanted the elderly to have to get a permit, thank goodness they didn't do it. They infantilize us" Woman, 62 years old.

In addition, some of them made mentions about the decree of social, preventive, and mandatory isolation as "house arrest", "dictatorship," or "loss of freedom". An explicit discomfort was identified in most interviewees regarding the project of requesting permission to leave their homes.

"Stopping errands and not going out makes me feel under house arrest." Male, 76 years old.

"They say you didn't lose anything, I lost my freedom." Woman, 73 years old.

2. Coping resources and coping strategies

We define coping strategies as those cognitive and affective efforts aimed at managing internal and environmental demands that test or exceed personal resources [29]. Thus, a strategy will be effective depending on the subject's ability to adapt. This implies an effort, an ability to manage or reduce the discomfort generated, in this case, by isolation. It then appears the maintenance or initiation of attitudes or activities to overcome the problem of confinement.

Some of the resources that appeared most frequently among the interviewees are those linked to the occupation of outdoor spaces, such as walking in the garden of their homes, or the dedication of long hours to gardening and vegetable growing; working with plants and flowers, or mowing the lawn. It would seem that contact with nature would have a beneficial effect on maintaining isolation in their homes without feeling cooped up.

"I'm very solitary, I entertain myself a lot with plants. I do rose bushes, I am more into flowers; now white roses, red roses, pinks. I'm already making buds and I'm waiting for spring to sprout.... alone." Male, 65.

"Luckily, I have a park in the background, I like to mow and keep it groomed. It's only when the sun goes down that I go into the house." Woman, 74 years old.

On the contrary, those interviewed who live in an apartment and do not have these outdoor spaces have referred to feeling "closed in" and expressed their need to interact with the outdoors, even if this means exposing themselves to a greater risk of contagion.

Other examples of overcoming activities were those related to health care, such as physical activity, yoga or meditation techniques. For others, the need arose to find a sense of meaning to diminish the feeling of "uselessness", and so they started "home-based businesses" such as the selling of wooden handicrafts or hand-knitted coats. Others took advantage of the opportunity to make repairs to their homes or redecorate. They also used the free time to read or resume foreign language classes.

"Then I thought I can put things together for little gifts, until the doors open and sell in my garage, for example." Woman, 61 years old.

It is essential to understand that these coping strategies appear to sustain the person in a given situation, but their maintenance over time makes us reflect on the extent to which these behaviors are adaptive or maladaptive. We observed that several behaviors of the participants seem to respond to a logic of "harm reduction", where, in an attempt to escape from negative thoughts, overcoming practices appear that are far from being considered healthy habits. We understand these new habits as a strategy to go through boredom and loss of routine.

"At 19 o'clock I take a bath, at 20 o'clock the whiskey, 21 dinner with red wine with my wife, later some champagne. I usually drink quite a lot, but now that I have more flexible schedules a bit more." Man, 72 years old.

We also identified other types of coping strategies related to the emotional memory of past traumatic events. As an example, one participant stated as follows:

"But I'm not afraid, I've already spent 4 lives and I have a few more left still haha. I overcame skin cancer, a heart attack, they wanted to mug and shoot me and the bullet didn't come out, even the dictatorship wanted to kidnap me in 79 but at that time I could run fast". Man, 76 years old.

2a. Older adults and technologies

The current context of confinement made it impossible for older adults to continue their routines actively, a situation that gave them the possibility of entering the world of technology for remote contact with their loved ones, an instrument that they had previously perceived as alien to them. By using different devices, they adapted to the circumstances and learned to be close, even if only through a screen, carrying out video calls with their family and friends.

"With my friends we communicate all the time by whatsapp or facebook. We have a close-knit group of friends, and even though we can't get together for tea like we used to, we stay close by cell phone." Woman, 73 years old.

Some interviewees recounted their positive experiences at the first virtual birthday parties. With this overcoming attitude, they went through their forties, leaning on their loved ones, in constant company. On the other hand, they were also able to maintain contact with their doctors remotely, carrying out consultations and health check-ups that gave them the peace of mind of feeling protected, close to the representative figure of the doctor, and far from the insecurity caused by the pandemic. In any case, the focus on access to the health system will be analyzed in the following article by the same methodological team.

"I am a bit worried about my health because I have to have a blood test, I haven't had one for a long time. I have to contact my family doctor who sent me the prescriptions online until the six month. I received well, but now they do not attend to me. That makes me nervous. And I already thought that when the prescription is ready I am going to ask them to send it to me by delivery. I'm afraid to go out." Woman, 76 years old.

They saw their autonomy as independent people strengthened and found solutions to their daily life problems through the Internet, such as, for example, the possibility of ordering their medicines or groceries by delivery, avoiding further exposure to the virus. They also found a means of entertainment where they could access books of their interest, movies, or series. In some cases, they had the opportunity to learn new hobbies through video tutorials and even to do physical activity. In this way, they abandoned the monotony of confinement and took advantage of the opportunities offered by the world of technology.

"In this time I learned a lot about technology and the positive side of it. Before I depended a lot on my children, now I learned a lot on my own; maybe with their help, but I had to learn myself. Now I don't go to the office anymore. Woman, 64 years old.

3. Affective states

The pandemic situation triggered states of anxiety that, accompanied by the present uncertainty, kept people ready and in a constant state of alert in the face of the threat of contracting the virus. Uncertainty was recognized as an invisible enemy, a stressor that can seriously affect people's quality of life, especially in older adults [30].

The primary emotions identified were distress and fear. Although there are validated instruments that allow diagnostic approaches to affective disorders via telephone, our research focuses more broadly on affective states regardless of the presence of a disorder. Thus we observed in several participants that distress and fear deepened from overexposure to news or media, which influenced their negative thoughts and attitudes.

"I only watch a morning newscast and another one in the evening, it makes me sick. Woman, 87 years old.

"One distrusts everyone, the media doesn’t express themselves in the best way. You don't know if they are telling the truth or they are lying to control the situation, to instill fear...". Woman, 68 years old.

During the first months, we noticed that the fear of contagion predominated, showing attitudes of extreme care guided by this factor, such as the constant cleaning of the home, the application of cleaning products on any element that entered from outside, and experiencing the feeling that the invisible enemy could be present anywhere. In this way, they chose not to leave their homes under any circumstances, avoiding any contact with the outside and transforming their homes into an "antiseptic bubble".

"I worry when I watch TV, I am afraid for my children who go to work, for those who are outside. It makes me afraid, anxious, that we don't know what might happen. But I pray and play music." Woman, 74 years old.

We also found a response to fear as an obstacle to care for other conditions or illnesses:

"I called the cardiologist to make a video call. My chest was hurting a little. It took them a long time to answer and when I spoke I told him: 'Next time, take care of me before I die [...] But I don't want to go to the hospital, I can't stand it. I feel locked in, I can't go out." Woman, 76 years old.

With the successive extensions of the lockdown and the prolongation of isolation, we noticed an increase in expressions linked to irritability, anger, boredom, and tiredness, reaching the point of exhaustion. Several of them expressed these emotions linked to the impossibility of seeing their grandchildren.

"Today we are tired, we need to see our loved ones without feeling so persecuted. It was stretched too far and it is truly a problem for everyone, especially from the emotional side." Woman, 68.

"I have little grandchildren, that bothers me, I can't see them, it makes me angry. There are things that are never to be repeated again." Woman, 71 years old.

Another element we observed in the participants was sleep disturbance. Many of them experienced nightmares, insomnia, changes in waking hours, or even staying in bed longer, even when they were already awake. In addition, there was evidence of an increase in the consumption of anxiolytic drugs without prior consultation with a medical professional.

"I get up late so it makes the day shorter". Female, 74 years old.

"I increased the dose of Clonazepam 0.5 mg more since the pandemic started, it helps me sleep. With this I don't wake up every now and then." Female, 68 years old.

Finally, unfortunately, one participant with a history of pre-existing severe psychiatric pathology committed suicide during the research period. We had conducted an initial interview, and when scheduling the follow-up interview, we learned what had happened. The participant had a small family network consisting of her mother and pet. In this context of isolation, her mother was hospitalized for an intercurrent illness, and her pet died. The event in question allows us to reflect on the importance of the bonding networks in a person's life and how the lack of these networks can perhaps leave the person without resources to continue.

4. Perceptions and reflections on the future

The pandemic and the consequent isolation measures put routines on "pause". Isolation brought with it time to think, especially from an introspective point of view. We found in the interviewees a need to reflect on the future, on the world around them, and of which they are a part. Due to the impossibility of thinking about the near future, a sense of uncertainty was repeated in the stories. We even found in several participants reflections about death, and the finiteness of life around the little time remaining, and the feeling of loss of time from the confinement in their homes.

"I feel that at my age and at this point, I will never be able to resume my normal life again. I can't see a future, it's been so long that one is getting used to this normality and I don't see, from my age, my point of view, a normal future like before, I'm not telling you that it distresses me, it humors me" Woman, 69 years old.

"Will the lockdown be over? What is life going to be like after that? Will the virus be completely eradicated? Will what's left of my life be an eternal lockdown? Will we see each other in heaven directly?" Woman, 77 years old.

Several interviewees shared their concerns about a "more robotic" future, worried about what their affective modalities will be like, whether hugs will return, and how encounters with virtuality will change. They also expressed concern about how children and younger people will continue their lives, even thinking that perhaps some of what came in this context is here to stay.

"They are happy inside. They don't have the need that one has. They get used to being inside a room and it seems normal to them. I'm seeing that big change and it scares me, I'm seeing them coming out turned into robots. They are happy to be in Zoom video calls, through the devices. It's like generational [...]" Female, 63 years old.

Others expressed concern that the fear of contagion would indefinitely modify their way of life, especially in relation to the attitude of suspicion about those who might carry the virus, generating in some participants a rethinking regarding their work-life and contact with others.

"I don't know when people are going to let me put my hands on their body, put pins on it, touch it, measure it, nor if I'm going to be able to, or want to. I'm going to be doubting whom I was with, if they have or don't have COVID." Woman, dressmaker, 61 years old.

5. Participatory action

We explored the possibility of a research-action approach, which was crossed by the coordinates of the context and the repeated extensions of the lockdown, at the same time that we learned more about our own experience and that of others in these circumstances. On the other hand, it was essential to share the findings at the group level in the weekly meetings of the research team via Zoom. These allowed us to rethink and re-question different situations that arose during the interviews and share views among the researchers to think of unexplored alternative approaches.

After the first telephone contact with the participants, we realized that the follow-up and repeated contact with some interviewees were part of a participatory action process to which we were invited. When addressing emerging needs and coping measures, the idea of coordinating a participatory activity such as an online workshop or a reading group arose. This proposal arose intending to contact two participants who had the same motivation to learn Italian. Other participants wanted to make a video tutorial of their cooking skills to share through social media. In this context, questions arose such as: what to do with these motivations that they present, how to help to convey them? Thus, we proposed setting up a Facebook group, thinking that they could share content and even get to know each other and talk to each other. However, this last proposal was not well received by the participants and was later rejected.

As the weeks went by, we discovered that the power of the action was in each call. That in this position of active listening, the other person was enabled to share something of his or her experience of the situation. Thus, in one of the calls made by a researcher, it was identified that a participant was disoriented and distressed. From this situation, we contacted this person's daughter to make sure she was okay.

What are the effects of an encounter for these participants? Perhaps in the motivation of a lady who decides to start a business based on her handicrafts because she feels she has something to share, or another participant who commented that her objective was to write a book on the knowledge of old age to share with her grandchildren. It was difficult to establish an evaluation of these results because the state of confinement was proposed as a global suspension of activities, in which every fifteen days, the participants waited for the isolation to be "lifted", which, to date, has not arrived.

Discussion

Main findings

From the interviews, we were able to account for emotional aspects and emerging needs arising from isolation, as well as the support networks they have. We can only think of the heterogeneity and complexity of the findings if we include in our approach the complexity paradigm of the contemporary philosopher E. Morin, who thought of complexity as a fabric of events, actions, interactions, retroactions, determinations, chances, which constitute our phenomenal world [31].

Each participant, as well as we as researchers, are crossed by multiple psychosocial, historical, and economic factors, and in this context of a pandemic, we were able to find among the most frequent emotions the fear of contagion of themselves and their loved ones, anguish, anxiety, anger, uncertainty and weariness or boredom linked to the extensions of the lockdown. On the other hand, as ways of coping with these needs, we found that older adults were incorporating various strategies to cope with the situation in the service of their psycho-emotional balance. They used technology as a bridge and means of communication to stay connected with their loved ones (having their support networks as an indispensable factor), even learning how to shop, take classes, and solve paperwork.

We explored the personal social networks of the older adults, these being "the sum of all the relationships that an individual perceives as meaningful, or defines as differentiated from the anonymous mass of society" [32], and found a relationship between these and the way in which the participants experienced isolation [31]. The people we found suffering the most were those living alone, in small and closed environments, fragile networks, or who did not have a good command of technology. On the other hand, those participants who had strong and stable bonding support networks reported less discomfort at the onset of lockdown.

Relationship with other research

Social isolation is a condition with a high prevalence among older adults [33], and there is extensive literature linking it to increased morbidity and mortality. A meta-analysis conducted in 2010 [34] that included 148 longitudinal studies, with 308,849 participants with a mean age of 64 years, indicated that people with poor social support network have a 50% higher probability of dying than those individuals with a good social network (OR 1.50 CI 95% 1.42 to 1.59). To account for the magnitude of this association, it will suffice to say that social isolation influences morbidity and mortality similar to other well-known variables such as smoking [35], arterial hypertension, obesity, and sedentary lifestyle [36],[37]. Our research did not evaluate the effect of isolation on these outcomes, however, the effects on health care were analyzed. This is described in more detail and at greater length in the second part of the manuscript [38].

In the first days after lockdown went into effect, an extensive report was published by the Social Sciences Commission of the COVID-19 Coronavirus Unit of the National Council for Scientific and Technical Research (CONICET) of Argentina, whose general objective was to provide information on the social impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic throughout the national territory [39]. According to the information provided by 1487 territorial referents, as key informants, emerging difficulties were reported to comply with lockdown and to adhere to care guidelines, where difficulties related to subsistence-work are highlighted, a situation that we persistently detected in our research months later. In contrast to our research, this study reported a worsening of the isolation situation in the elderly population related to more vulnerable socioeconomic contexts with limitations in accessing support networks, a population that was not included in our sampling.

The TIARA Study survey [40] analyzed the psycho-social and daily life impact generated by the appearance or circulation of COVID-19, as well as the implementation of the first stage of lockdown in Argentina (end of March 2020) and coping strategies. Their findings were consistent with our research: worsening in sleep, concern around one's health, the emergence of coping strategies such stopping the consumption of bad news from the media, the use of social networks to get informed and stay connected, or daily communication with family and friends. However, considering that only 12% of the participants were older than 60 years, boredom was not a major concern, and fear of job loss and other economic issues predominated. The survey was self-administered, anonymous, online and was conducted in a time period between March 30 and April 12, 2020. In parallel, another survey was conducted online for 32 hours with 10,053 participants from Argentina over 18 years of age (mean age 45 years) recruited in snowball by social media [41]. More than one-third of the respondents showed depressive symptoms between 5 and 7 days after the onset of the national lockdown, with younger people between 18 and 25 years being more affected, outside the range included in our research.

In relation to coping strategies, it is proposed that lived experiences influence how we perceive adversities of the present. This is why people who have suffered traumatic events could face adverse situations with greater resistance and resilience to process the stressful situations and distress they have experienced [42]. In our research, we found a diverse range of cognitive, emotional, and behavioral coping responses. We were unable to explore the degree of adaptability/disadaptability of these, and future research may investigate this aspect further.

Research from the United Kingdom and the United States identified a considerable increase in the perception of loneliness [43] and concerns about the future [44],[45]. In a rapid literature review published in February 2020 [46], 24 articles from more than ten countries were analyzed to assess the psychological impact of lockdown on the general population and health professionals, finding negative effects of confinement on symptoms of post-traumatic stress, confusion, anxiety, and anger. In addition, stressors such as fear and the perception of authoritarian restriction of freedom, a concept that we have repeatedly perceived in our participants, were identified. Another synthesis of evidence found deleterious effects associated with social isolation and psychological and emotional losses during the pandemic [47]. This information from other pandemics coincides with recent research findings in the Spanish population [48].

Weaknesses and strengths in our research

Our study has some limitations. First, due to restrictions on movement imposed by lockdown and technological limitations of the participants, we were unable to conduct interviews in person or by video call, considering that the telephone interview may not adequately capture the subjectivities that our study was trying to survey. In addition, telephone communication could be limited by cognitive impairments and pre-existing chronic pathologies prevalent in older adults, although we did not detect obvious problems in this area. Secondly, in order to achieve a bond of trust when conducting the interviews, we carried out a snowball sampling, which restricts our study to middle-class people from the Buenos Aires metropolitan area and, in some cases, people with some degree of relationship with the researchers. Thirdly, also linked to the method of access to the field, we were unable to access more isolated people, with fewer support networks and greater social and economic vulnerability. Fourth, although we had a second and even a third contact with some participants, in the vast majority (75%) we had a single encounter that may not have captured the dynamicity of the psychic phenomena that occurred during the isolation, including the prevalent and incident psychopathologies. Fifth, some of the researchers had difficulties in getting the interviewees to provide a new contact that met the inclusion criteria and became part of the project. Finally, in order to respect the limits of the participant's privacy in a telephone interview, a careful balance was maintained in the degree of invasiveness of the questions and the depth of the content addressed, so that some concepts could have been partially explored.

One of the strengths of the study is that we were able to conduct a substantial number of interviews with relevant content in a very difficult context in which the researchers themselves were also in preventive isolation. We met weekly and actively discussed the implications of our isolation on the interpretation of the data. We explored points of view considering geographic and gender diversity, and the interviewees felt comfortable sharing their experiences freely, even on those more sensitive details such as "lockdown violations". We think that the age difference between the interviewees (older adults) and the interviewers (undergraduate students) may have acted as facilitators. We followed a systematic methodology of recording and coding the interview data, and the analysis was triangulated by various researchers (from the fields of medicine, psychology, and sociology). We processed the data expeditiously since we consider it useful for future research and decision-making (see implications). Finally, we report the study following international standards of transparency in qualitative research.

Implications of the findings

We conducted this research in an unprecedented and complex context in which multiple factors that modify the psychosocial health of older adults intervene and are affected. For this reason, based on the results obtained, we consider the implications of our findings in terms of mental health at different levels.

In the general public

It would be important to reflect on the effects of overexposure to pandemic news on coping skills and the possibility of generating excessive worry, anxiety, irritability, or hopelessness. It is also important to recognize that dysphoric emotional reactions are expected, and understand their transience and coping strategies can help, especially in social support, maintenance of routines, and healthy drinking habits; avoiding excessive use of alcohol other substances. Staying active with chores and physical activity, especially outdoors, can be important, as an eventual professional consultation.

For policy makers

Although our study has limitations in transferability, it allows us to reflect on possible implications for public policies such as: effective communication of policies, the importance of accessibility to mental health services, and the guarantee of virtual media, especially in more vulnerable and isolated populations.

For health professionals and systems

Active listening makes it possible to accompany and identify both emerging conditions and the strengths and coping strategies available, accompanying and articulating, if necessary, with specialized care devices, especially in people with pre-existing conditions. Health systems should contemplate the challenges of mental health care for older adults in confinement, taking into account the existing technological barriers.

For future research

Considering the limitations of our study, it is necessary to evaluate the regional and socioeconomic variations of the observed phenomena, especially their variation over time, in the implications in the models of accompaniment and care at the community, health, and social levels. A special focus requires evaluating the most vulnerable subgroups that are likely to require specific preventive and rehabilitation strategies not covered in our current study. In turn, it would be important to quantify the impact of isolation on the incidence of affective disorders.

Conclusions

The study participants reported fear of contagion of themselves and their loved ones, anguish, anxiety, anger, uncertainty, and weariness or boredom, linked to the establishment and extension of lockdown in the context of the pandemic. However, we found varied coping strategies to cope with the situation in the service of their psycho-emotional balance. Technology was a fundamental actor in the maintenance of family ties and other affective needs. We identified people in a situation of greater vulnerability when living alone, in small and closed environments, fragile bonding networks, or limited use of technology. The findings of this research have implications for decision-making at the individual level, health systems, professional care, and policy development. Future research may elucidate regional, temporal, and socioeconomic variations in the phenomena explored in our investigation.