Research papers

← vista completaPublished on May 22, 2023 | http://doi.org/10.5867/medwave.2023.04.2610

Cross-sectional study on the application and perception of acquired bioethical knowledge in health professionals from pediatric emergency departments

Estudio transversal en profesionales de la salud sobre aplicación y percepción de conocimientos bioéticos adquiridos en urgencias pediátricas

Abstract

Background Compared to basic or applied clinical sciences, bioethics is frequently considered as a secondary discipline and underutilized in daily practice. However, ethical reasoning is indispensable for the quality of care. There are few studies on bioethics in pediatric emergency units. Our objective was to evaluate the perception of the acquired bioethical knowledge and the application of bioethical principles in standardized cases.

Methods We conducted a cross-sectional descriptive study in medical and nursing professionals working at pediatric emergency units in Puerto Montt. Through a survey, we assessed the perception of the sufficiency of the acquired bioethics knowledge and the application of bioethical principles on hypothetical, but probable cases in emergency pediatric care.

Results Of a total population of 50 physicians and 53 nurses, 30 physicians (60.0%) and 20 nurses (38.7%) participated in our study. The majority reported ethics training in undergraduate education: 84%. A minority reported training during practice: 20%. However, only 60.0% perceived having sufficient knowledge of bioethics and 72.0% considered it important for daily practice. Further, when applying the principles of Beauchamp and Childress to standardized clinical cases, 82.7% did not recognize the justice principle and only 50.00% the principles of autonomy and nonmaleficence.

Conclusion Although most health professionals undergo bioethics training, learning is often considered insufficient and not incorporated into daily practice at pediatric emergency units.

Main messages

- Clinical medical ethics and bioethics in recent decades are learning objectives during undergraduate and graduate education of healthcare professionals. This knowledge is expected to be applicable during job performance in all healthcare settings.

- Assessing the perceived sufficiency of acquired bioethical knowledge and its application in the workplace allows us to detect the importance assigned to this knowledge by healthcare professionals and future training needs.

- This work is the first study carried out in Chile in emergency units. Its results may contribute to emphasizing the importance of ethical reasoning in emergency units, modifying the curricula of healthcare professions, and conducting continuous training courses for in-service pediatric emergency professionals.

- The low participation of the targeted population is a limitation of this work. In addition, there are subjective responses regarding the perceived sufficiency of knowledge in bioethics.

Introduction

In the modern concept of health, bioethics was incorporated into health professionals' curricula in 1990 in some universities in Canada, the United States, and other universities worldwide [1,2,3,4]. In Latin America, it began less than 30 years ago. Initially, in some universities, it was incorporated as an elective subject. At the beginning of the 21st century, it was taught as a mandatory one-semester course during the first years or before professional practice or internship. It was also taught as a cross-cutting elective [5,6,7,8,9]. Consequently, learning bioethics in different countries and universities, even within the same country, has not been equivalent in terms of duration, content, or learning methodology. The profiles of healthcare careers expressly state that their graduates have solid bioethics knowledge and that they are expected to apply it in their professional practice. However, it has been detected that learning has been insufficient during undergraduate training, which has motivated research on new teaching methodologies [10,11].

This study aimed to evaluate the perceived importance and sufficiency of the acquired theoretical knowledge and the application of bioethical principles in standardized cases without immediate vital urgency, which are frequent in pediatric emergency care units. We chose the emergency context since, in Chile, the knowledge of bioethics in the medical profession has been investigated in pediatric critical patient units [12], but to our knowledge, it has not been carried out in emergency units.

Methods

We conducted an exploratory, descriptive, cross-sectional study. A validated questionnaire on bioethics teaching in undergraduate and postgraduate courses, the perceived sufficiency of acquired knowledge, and the perceived importance and applicability of bioethical knowledge in daily clinical practice was applied. The analysis was based on the Beauchamp and Childress principles: autonomy or respect for patients' opinions and values, beneficence or quality care, non-maleficence or avoidance of harm, and justice or correct use of the patient’s and the institution’s economic resources, applied to frequent non-life-threatening clinical cases. The instrument was provided to all physicians and nurses who agreed to participate and work with the pediatric population in the emergency units of Puerto Montt Hospital and clinics.

The questionnaire was constructed from the validated surveys of Hebert, Fawzi, and Rueda [1,4,6]. These authors used clinical cases to determine whether bioethical concepts have been incorporated and asked whether, with the learning strategies used in undergraduate studies, students considered they had the tools to apply them in their daily work. This questionnaire was presented to doctors in bioethics from the Santiago and Desarrollo universities and members of the healthcare ethics committee of the Puerto Montt Hospital; all of them, considered experts in clinical and research bioethics, gave their opinion on the questions and variables included. Subsequently, a pilot test was conducted on ten physicians and nurses, modified according to the suggestions and approved by the scientific and ethical committee based on the validation of the Villavicencio 2016 questionnaires [13].

Data were requested on age, professional degree, years of professional practice in emergency units, type of emergency unit, undergraduate ethics training including placement in the academic curriculum and teaching methodology (theoretical, practical, or a combination of both), postgraduate ethics teaching as part of a postgraduate curriculum or as continuing education, perception of the adequacy of knowledge acquired for professional performance, and identification of Beauchamp and Childress' four bioethical principles in a list of ten ethical concepts (autonomy, beneficence, quality, efficiency, empathy, justice, mercy, non-maleficence, prudence, and solidarity) containing four principles and six distractors.

Concomitantly, five fictitious but possible clinical cases were presented in emergency consultations, in which at least one of the principles was asked to be selected from five alternatives that included Beauchamp and Childress' principles, together with distractors. Finally, a Likert scale with five items (1 strongly disagree, 2 disagree, 3 indifferent, 4 agree, 5 strongly agree) was included in determining the opinion on the relevance of ethical knowledge in professional practice in the emergency unit, the place within the curriculum where this knowledge should be delivered, and the interest in future bioethical training. This was an exploratory and descriptive study, so the questionnaire was not subjected to statistical validation.

For the targeted population, invitations were emailed (two to three times) to service chiefs and all physicians and nurses employed in emergency units, enclosing informed consent and a questionnaire (Annexes 1 and 2). At the same time, the authors delivered the documents in person to some professionals at their workplaces, collecting them back within 15 to 30 days. The questionnaires were self-administered. The total data collection period lasted 12 months (May 1, 2021, to April 30, 2022) due to the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Physicians and nurses working in emergency units in Puerto Montt, caring for the adult population, and other health professionals were excluded.

This study was authorized by the scientific ethics committee of the Reloncaví health service, which includes the provinces of Llanquihue and Palena, covering an area of 30 178 square kilometers, with an estimated population of 466 521 inhabitants. Likewise, the informed consent process consisted of providing detailed information to the participants, who were required to sign a consent form.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed with IBM® SPSS® Statistics 20.0 SPSS software and Microsoft Office Professional Plus 2013. Descriptive statistics (number of cases and percentages) were applied. Bar graphs were used to represent the level of knowledge delivery and the importance attributed by professionals to the study of bioethics.

Results

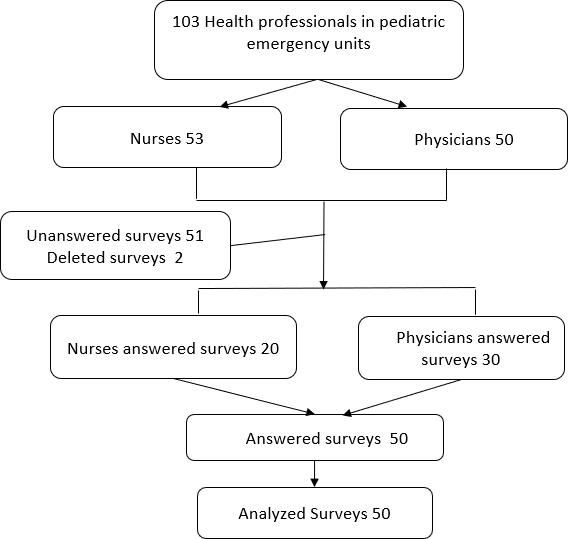

Of a total population of 50 physicians and 53 nursing professionals, 30 physicians and 20 nursing professionals participated, constituting a sample of 50 professionals, equivalent to 48.5% of the targeted population. Regarding the professional category, 40% corresponded to nurses and 60% to physicians (Figure 1).

Flow diagram with the participants' characteristics.

Regarding age, 26% of the professionals were under 30 years of age, half of them had less than 10 years of professional practice, and 66% had less than five years of service caring for children, which characterizes a preferably young population. Twenty percent of the professionals worked in both emergency services (public hospitals and private clinics); the largest percentage worked only in private emergency units (Table 1). When disaggregated by professional category, nurses worked preferentially in private care, while there were no differences in the physician category in relation to the workplace (data not shown in the table).

Regarding knowledge or learning in bioethics, 84% of the professionals received ethics training as undergraduates, 26% in their first years of study, and 20% during their internship or training, while only 16% had some bioethics training as postgraduates. Regarding the perception of knowledge about bioethics, 60% are estimated to have sufficient knowledge (Table 2).

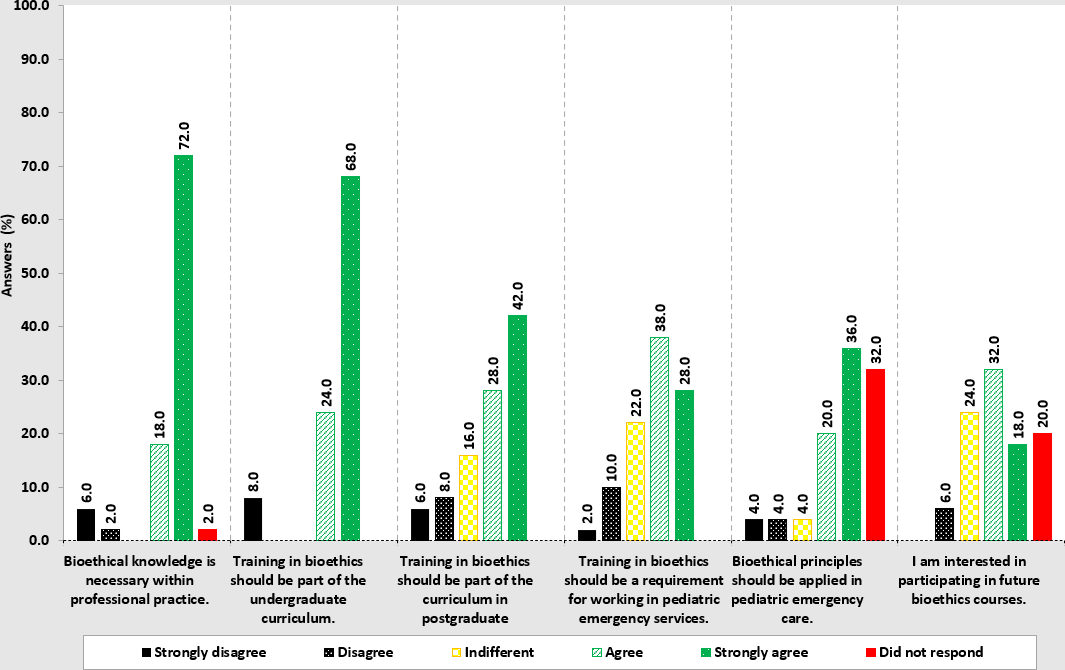

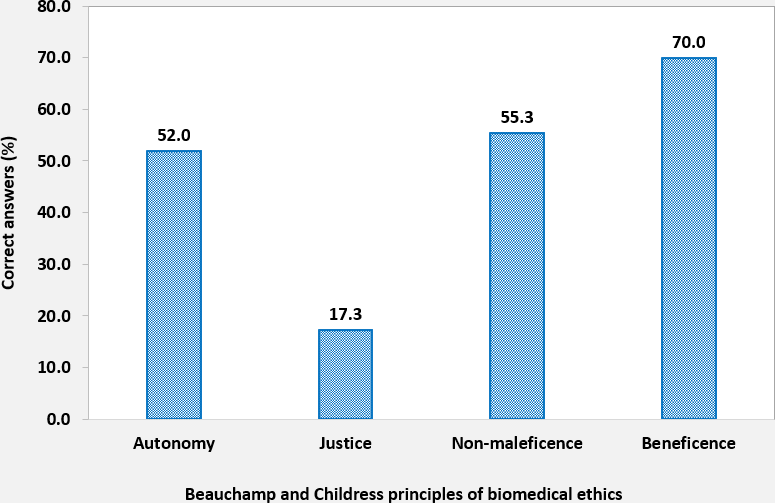

When asked about the importance of bioethics training in undergraduate and continuing education for work performance, 72% stated that knowledge of bioethics is important in professional practice; however, 18% were indifferent. At the same time, only 56% believe that the four principles of Beauchamp and Childress are applicable in pediatric emergency care. Regarding the presence of bioethics in the curriculum, 92% responded that it should be in undergraduate and 70% in postgraduate courses. Even though a high percentage of those surveyed thought that knowledge of bioethics is relevant for postgraduate training, 24% were indifferent, 6% disagreed with deepening their training, and 20% did not answer. When asked whether bioethics training could be required to work in pediatric emergency units, 66% of the professionals agreed or strongly agreed (Figure 2). When analyzing the percentage of success in identifying the Beauchamp and Childress principles in the clinical cases presented, the principle of justice was the least recognized, with only 17.3% of the professionals selecting this principle when it was present in the clinical situation described. Regarding the principle of beneficence exemplified in case four, 70% of the professionals clearly identified it. When asked about the principles of autonomy and non-maleficence, 52% and 55.3% of the professionals surveyed could recognize them (Figure 3).

Graph of professionals' responses on the assessment of bioethics knowledge in professional practice and the need for undergraduate and postgraduate training.

Average percentage of correct answers in the identification of Beauchamp and Childress' principles, created by authors based on the results and Table 3.

Discussion

Our results show that, although most professionals (84%) responded that they had received bioethics training as undergraduates, only 60% considered that the knowledge they had acquired was sufficient for their work. Those who have not received it correspond to older professionals with more than 20 years of professional practice, who were trained when bioethics subjects had not yet been formally incorporated into the curricula of healthcare careers.

International and national studies show that in recent decades healthcare professionals have received education on the bioethical aspects that determine a correct professional performance as part of the university curriculum. These bioethical aspects apply to all clinical healthcare settings [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9]. In recent years, the outcomes of this learning have been investigated in medical schools, medical students, nursing students, psychology, and other health professions, as well as in experienced physicians. These studies have measured ethical sensitivity to identify ethical problems through the Beauchamp and Childress principles, the degree of satisfaction with the teaching provided, what content the course should include, at what stages of the curricula, and with what learning methodologies it should be delivered, the influence of the hidden curricula, and the incorporation of knowledge in the workplace. Studies point out that even in countries with a vast history of bioethics teaching, incorporating Beauchamp and Childress' bioethical principles and ethical deliberation into routine clinical practice has not been achieved [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9].

In Chile, the study by Morales et al., which had a 67% response rate to a self-administered questionnaire, described the physicians' bioethical knowledge and attitudes in critical patient units in relation to the adequacy of therapeutic effort, showing that only 24% of the respondents had formal studies in bioethics. This is despite the fact that bioethical problems are highly prevalent in critical units. Although undergraduate training was not specifically studied, the study concluded that training in healthcare bioethics is deficient and that efforts should be made to improve training [10]. House et al., using medical student trials, highlighted the unique characteristics of the emergency department setting in the face of potential ethical issues related to healthcare and how this clinical setting could be used to practically teach the ethical principles of autonomy, non-maleficence, justice, and beneficence. In addition, they highlighted virtues related to professionalism, such as respect for others, providing appropriate care, and concern for vulnerable patients [11]. Rainer et al. and Barlow et al. reported that in nursing, it is possible to identify and respond to ethical dilemmas in patient care [14,15]. Colaco et al. emphasized that ethical challenges in pediatric emergency care are more prevalent than in adult emergency departments and that nurses and physicians need further ethical education to adequately manage the multiple ethical issues identified [16].

Considering this background and the fact that we have not found any work that specifically evaluates the perception of theoretical knowledge in bioethics and the application of ethical reasoning with the methodology of clinical case analysis based on the principles of Beauchamp and Childress, we decided to investigate these concepts in public and private emergency units in Puerto Montt, a healthcare reference center for the provinces of Llanquihue and Palena.

We used the mixed survey methodology, emailing the questionnaire and multiple reminders, and personal delivery of the informed consent and questionnaire. Given the advantages of this methodology, we used this procedure to improve the response rate in a high-demand critical care unit such as the emergency unit, particularly during the pandemic lockdown [17]. Sixty percent of physicians and 37.7% of nursing professionals agreed to participate in the research, which is close to response rates obtained in online survey research studies [17]. In this sample, both physician and nursing professionals with less than 20 years of service and younger than 50 years have had ethics training during undergraduate, which is explainable by the year of introduction of bioethics in the curricula of health schools. Of particular significance is the fact that, during undergraduate training, the teaching of bioethics took place preferably in the first years of study and only 23% during the period of professional practice, when learning based on experience is more likely to take place. This coincides with the work published in other North American, European, and Latin American countries [2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9].

Regarding the importance of knowledge in bioethics for professional practice, most of our study population (90%) agreed that it is relevant. Although 60% perceived that they did not have sufficient knowledge of bioethics with the training received at the undergraduate level, only 22.5% agreed with taking bioethics courses, 24.0% were indifferent, and a similar percentage did not answer concerning further training, which translates into apparently contradictory results that agree with what has been published in other countries. Defoor et al., in a multidisciplinary student population, reported that 92% considered bioethics teaching useful for the future of their careers, but only 60% expressed interest in more ethics education [8].

When applying the principles of Beauchamp and Childress to typical clinical cases, it became evident that these are not routinely considered in care. Thus, in the first case, on transfusion without informed consent in a Jehovah’s Witness patient with mild to moderate hemorrhage that does not constitute a life-threatening emergency and in which other alternatives are possible considering his values and beliefs, the principles of autonomy and justice have not been recognized when using a therapy of limited availability without consent.

In the second patient, with acute lymphoblastic leukemia, whose prognosis and behavior are previously defined by the treating physicians and informed to the family members, the diagnostic and therapeutic measures indicated are of high cost and restricted availability. In addition, they have an emotional, economic, personal, and institutional impact without benefit to the patient, which also shows that the principle of justice and even non-maleficence has not been considered. In addition, it is necessary to consider that in Chile, advance directives have not yet been implemented in pediatrics. For cases three and four of cold and acute catarrhal otitis media, which are self-limited pathologies of frequent consultation, the use of corticoids for a prolonged period and antipyretics despite a slight fever in the first case and the indication of numerous tests and drugs in the second case stand out, which shows that the principles of non-maleficence and justice have not been taken into account either.

On the contrary, in case five, who was hospitalized, a detailed anamnesis and complete physical examination were performed, evidencing a severe high-risk case requiring immediate hospitalization in the critical care unit, and in which no studies were performed in the emergency unit that would have delayed invasive monitoring and complete laboratory and imaging studies in a safe environment, equipped with advanced monitoring and vital first-hour critical therapy; all principles were observed, particularly the principle of beneficence. In addition, the principle of autonomy was considered when signing the informed consent for hospitalization, which reflects a high-quality physician-patient/family relationship. However, 70% of the respondents gave the correct answer, which may indicate deficiencies in evaluating the specific pathology and signs of severity or lack of experience in assessing ethical principles in daily practice. The principle of justice, present in cases one and four, was only recognized by 17.3% of the professionals. Haan, Varkey, and Moss et al. reported the impact of moral or ethical deliberation of cases in different healthcare settings, pointing out the benefits for the patient and the healthcare personnel. The latter is often overburdened and exhausted, not only by the amount of work but also by the stress of unresolved ethical issues, including interprofessional relationships [18,19,20]. Vergano et al., recognizing the lack of medical bioethics education in critical care units, including emergency units, designed a new tool to teach medical ethics called Ethical Life Support (ELS), assimilating the Neonatal Advanced Life Support (NALS) and Pediatric Advanced Life Support (PALS) courses. These programs are mandatory for those who work in these units and use the A, B, C, and D methodology of these courses, where A stands for acknowledge, B for beware, C for communication, and D for deal [21]. This methodology emphasizes the notion that knowledge and application of bioethics should be among the requirements to work in this healthcare context.

The work of Kavas, Fawzi, DeFoor, Sullivan, Colaco, et al. also recognized the shortcomings of learning and the importance of the subject’s placement within the curricula, duration, content, and learning methodology to improve ethical competencies applied to care. They suggest that this course should be longitudinal, throughout all training years, especially in the final years [3, 4, 9, and 16]. Although there is no consensus on the best teaching-learning methodology, there is agreement that it should be mixed, theoretical-practical, prioritizing the practical so that ethical analysis or reasoning becomes a habit of daily practice [18,19,20].

Our health care system is organized into public health care, which serves approximately 80% of the population, and a private health care system. Therefore, our city has an older, larger, more staffed, and experienced public emergency unit and two private emergency units. Some professionals (20%) work in both. It is striking that the highest percentage of nurses surveyed work in private emergency units. However, the reason for this is that there was less participation in the research among public service nurses for reasons unknown to us, which would be useful to know for a future study. The physicians' response was equivalent in both types of emergency units. The performance in either health system, which represents the entire population of healthcare professionals working in emergency units, accounts for job opportunities and is not a differentiating element concerning the topics investigated. Nevertheless, it allows us to know the responses of a larger sample of professionals.

Meyer-Zehnder and Cederquist et al. have reported that among the factors that negatively affect the implementation of shared medical and ethical decision-making models in care are the lack of individual and institutional ethical knowledge and culture, the scarce recognition of the existence of ethical problems, the lack of acceptance of everyday ethical reasoning, and the lack of interprofessional collaboration. They even assimilate them to barriers and facilitators to comply with clinical guidelines [22,23].

Although many forms of ethical support exist, Siegler encourages the learning and practice of clinical ethics by integrating ethical principles into everyday clinical care. This requires the commitment and involvement of healthcare professionals in improving the care, prognosis of patients, and quality of services provided [2].

Baarle and Wehkamp et al. show how ethical reasoning is also involved in the quality of care provided, including recognizing adverse events associated with healthcare and how integrating these concepts can lead to significant changes at the individual and institutional level [24,25]. Finally, Asadabi makes an ethical guideline proposal for emergency medicine, emphasizing the need to incorporate ethical deliberation in this healthcare setting [26].

This study has limitations since 48.5% of the targeted population participated, and the number of participants is low. We did not obtain a response as to the reasons for not participating. Although there are no significant differences between those who participated in the study and those who did not, it would be interesting to replicate the study at the local level in those who did not participate, as well as in other pediatric emergency departments within the national or international setting, to observe whether the findings are replicable and to obtain more general results. Another limitation is that the perceived sufficiency of bioethics knowledge was a spontaneous and subjective response since we did not use a specific instrument to measure perception. However, we consider that this exploratory data could be valuable for planning improvement strategies both in undergraduate education and workplace education. It would be desirable to evaluate whether modifying the results with an educational intervention in the same targeted population is possible.

Among the aspects to be highlighted in this study, to our knowledge, this is the first study carried out in Chile in emergency units. The results could be useful in demonstrating the importance of ethical reasoning in the emergency unit, modifying the curricula of healthcare professionals, and carrying out continuous training courses for in-service pediatric emergency professionals. The latter could be carried out in interdisciplinary modules, with applied methodology, allowing to improve capabilities and quality of care.

Conclusions

Although more than 80% of the professionals studied bioethics as undergraduates, the learning acquired was insufficient to incorporate ethical analysis based on principles into daily practice in the emergency unit.

Considering that ethical reasoning has transcendental implications in patient care, avoidance of medical error, improvement of the quality of healthcare, and trust in healthcare professionals, along with the individual and institutional economic aspects that follow an objective application of the principle of justice, it is necessary to plan strategies for medical ethics education in emergency units.