Research papers

← vista completaPublished on March 14, 2024 | http://doi.org/10.5867/medwave.2024.02.2726

Desarrollo de una herramienta en español para ayudar en la toma de decisiones del cribado de cáncer de mama para mujeres de riesgo promedio: un estudio de métodos mixtos

Developing a breast cancer screening decision aid in Spanish for average-risk women: a mixed methods study

Abstract

Introduction We aimed to develop a decision aid to support shared-decision making between physicians and women with average breast cancer risk when deciding whether to participate in breast cancer screening.

Methods We included women at average risk of breast cancer and physicians involved in supporting the decision of breast cancer screening from an Academic Hospital in Buenos Aires, Argentina. We followed the International Patient Decision Aid Standards to develop our decision aid. Guided by a steering group and a multidisciplinary consultancy group including a patient advocate, we reviewed the evidence about breast cancer screening and previous decision aids, explored the patients' information needs on this topic from the patients' and physicians' perspective using semi-structured interviews, and we alpha-tested the prototype to determine its usability, comprehensibility and applicability.

Results We developed the first prototype of a web-based decision aid to use during the clinical encounter with women aged 40 to 69 with average breast cancer risk. After a meeting with our consultancy group, we developed a second prototype that underwent alpha-testing. Physicians and patients agreed that the tool was clear, useful and applicable during a clinical encounter. We refined our final prototype according to their feedback.

Conclusion We developed the first decision aid in our region and language on this topic, developed with end-users' input and informed by the best available evidence. We expect this decision aid to help women and physicians make shared decisions during the clinical encounter when talking about breast cancer screening.

Main messages

- This is the first decision aid in Spanish for this topic developed using international patient decision aid guidelines and the first decision aid in Argentina.

- We used a qualitative approach involving the end users of the tool and we pilot tested the comprehensibility, acceptability and usability of the tool.

- We included a small sample of middle-class women and did not test its effect in making shared decisions. Further studies are needed to establish the effectiveness and the transferability of the tool to other populations.

Introduction

Breast cancer is the leading cause of death from cancer in women[1

Shared decision making is an approach to inform and help patients make decisions tailored to their preferences and needs[9

In Argentina, previous studies conducted in a private hospital (Hospital Italiano of Buenos Aires) indicated that mammography screening was being overused in young women without risk factors for breast cancer screening and that patients' motivation to participate was based on incomplete information about its harms[15,19

Methods

Development

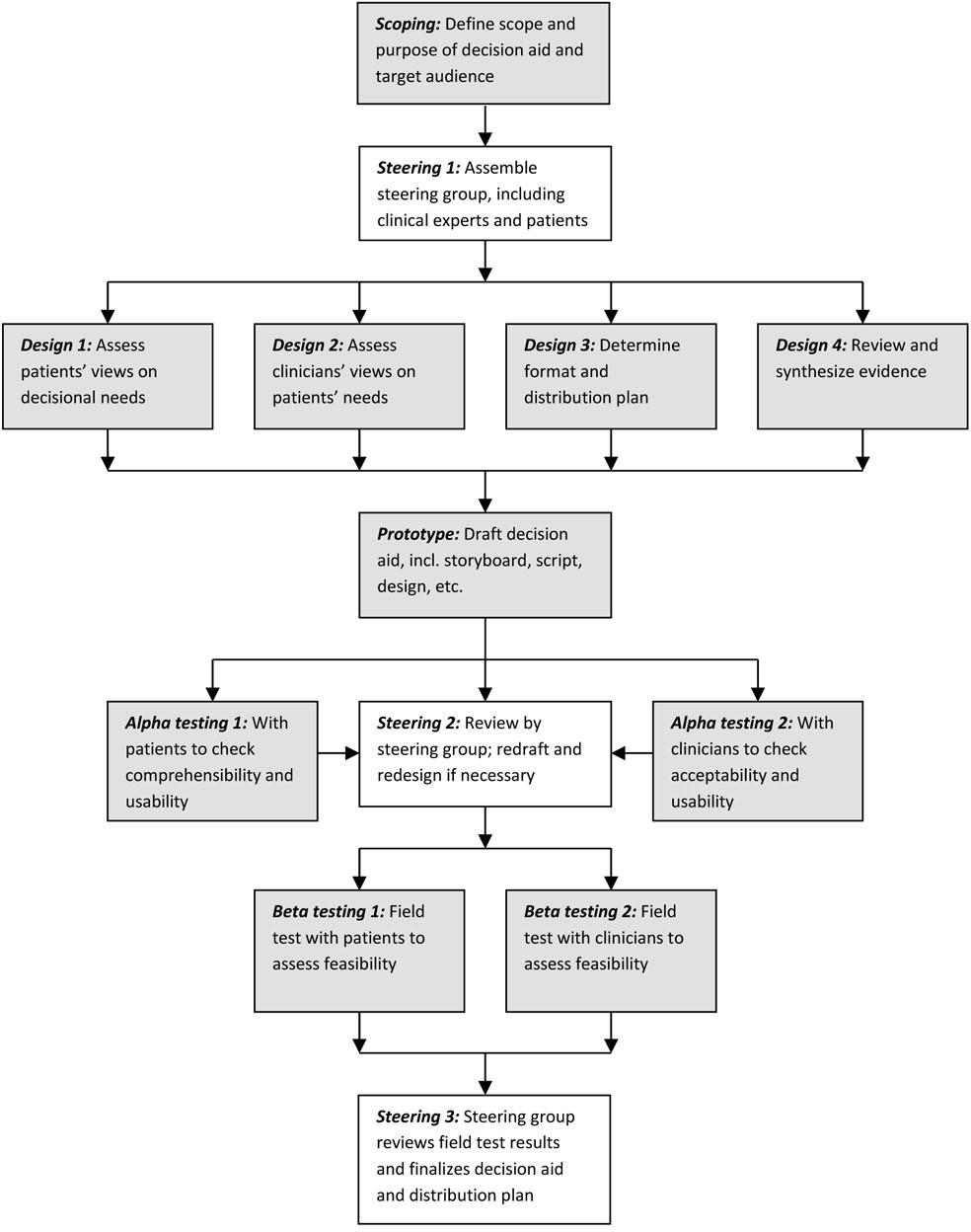

We conducted a mixed-methods study between 2018 and 2020, following the framework suggested by Coulter et al. for developing patient decision aids according to the International Patient Decision Aid Standards (see Figure 1)[21

Model Development Process for Decision Aids by Coulter et al.

Exploring patients' decisional needs

We used an interpretivist approach and selected a convenience sample of patients and physicians to elicit their views on patients' information and decision support needs for participating in breast cancer screening. Patients were women aged 50 to 69 years old, literate, affiliated to our institution’s private health insurance. We selected physicians that usually have preventive health care conversations with women, such as family doctors, gynaecologists and general internists, working at the Hospital Italiano of Buenos Aires. We conducted semi-structured interviews using an interview guide (included in the supplementary materials) based on the work of the University of Ottawa for assessing decisional needs[23

Content and format

Guided by our steering and consultancy groups, we performed a literature review of previous breast cancer decision aids and the evidence about the options, patients values, preferences and information needs regarding this decision to define the preliminary aspects of the tool [2,7,17,18,25–30

Alpha testing

Patients and physicians revised the decision aid to determine its usability, acceptability, and comprehensibility. We selected a convenience sample of 20 patients and physicians, and we collected data through an online anonymous survey (included in the supplementary materials) [31,32

Ethical considerations

Participation in this study was voluntary and confidential. The researchers that recruited participants and conducted the interviews had no relationship with the patients and were not in a position of power (e.g. employer, head of department) with the physicians included in this study. All participants signed an informed consent. The online survey was anonymous and the interview transcripts were anonymized prior analysis to avoid disclosing any personal identifying information. The files were password-protected and saved using unique identifiers.

Patient and public involvement

A patient representative joined our research team in the developing stages of the decision aid, providing input from the analysis phase of the interviews until the alpha testing. MR was also part of the consultancy group that gave feedback on the decision aid prototypes at different stages.

Results

Exploring patients' decisional needs

We interviewed 19 participants in total, seven patients and 12 physicians. Their characteristics are summarised in Table 1.

Based on the transcription of the interviews, we coded the responses and organised them into three main themes: 1) the choice of having a mammogram, 2) information needs, and 3) counselling and communication. Supporting quotations are included in online supplementary table 1 in the supplementary materials.

In general, women had already decided to participate in breast cancer screening as part of their regular check-up. Women saw mammograms as a non-invasive procedure, crucial to women’s health and even mandatory, influenced by the input of their families, friends and the media urging them to participate. Some women saw the screening as predominantly beneficial, minimising possible harms. Doctors acknowledged this and found it rare when women challenged the need to do a mammogram or asked about other options. Some of them expressed that women usually think that more is always better when it comes to screening or preventive interventions. Women and doctors mentioned that the ache and pain experienced while doing mammograms impact the patients' experience but do not prevent them from doing the study. They also concur that patients feel fear and anguish while awaiting results or if they had to repeat tests due to false positives.

Physicians thought some women ignored the currently recommended screening tests (mammogram vs ultrasound), the age when to start and the frequency. Mammography was perceived within a "package" of preventive interventions for women, some of which are not currently recommended (e.g., routine transvaginal ultrasound). Furthermore, some did not understand that a mammography is a form of secondary prevention (not intended to reduce the incidence of the disease). They agreed on informing about false positives and overdiagnosis, which are complex terms to grasp for both doctors and patients. Women wanted to know the benefits and harms of screening. They prefered to hear this information from their physician rather than from media campaigns or a brochure. They perceived a favourable balance between the expected benefits and harms of screening. When eliciting views on harms, most of them mentioned the pressure exerted by the mammogram as something that can hurt the breast tissue and the risk of radiation. A woman that had a personal negative experience with a mammogram’s false-positive result highlighted the need to inform women about what this entails. But others without this experience did not see false positives as harm but as something necessary and beneficial, something that needed to be checked in detail for their own good.

Patients and physicians identified a good doctor-patient relationship as a common facilitator to improve the patient’s understanding of different topics. One woman described the doctor as the most trusted source of information and as the final decision-maker. Physicians highlighted that it is important to have an institutional consensus about recommendations on screening and informative materials supporting what needs to be discussed during the consultation. Both physicians and patients agreed that lack of time during the consultation was a barrier to effective communication. Physicians stated that the changes in recommendations were also a challenge, especially concerning when to start and how often to recommend screening and suggestions regarding breast self-examination. Finally, the physicians identified that some patients have a firm belief about regularly doing mammograms. When they are presented with the option of doing them less frequently or not doing them at all, they are reluctant to engage in a discussion.

Content and format

We conducted targeted literature searches for primary research, other decision aids and systematic reviews based on the input of our expert steering and consultancy groups. We decided that we would gather the evidence on the following categories for the content of the decision aid: a) benefits or advantages of breast cancer screening, b) harms or disadvantages of breast cancer screening, c) information needs and women’s values and preferences regarding breast cancer screening, d) format and presentation of the decision aid (see Table 2) [33-39]. Initially, we evaluated the information needs of women aged 50 to 70 years (the screening target population according to our national guidelines). However, we also decided to include women aged 40 to 49 years in our decision aid to address the needs raised by our interviewees and because our previous research has shown women in both age groups have little knowledge about harms [15

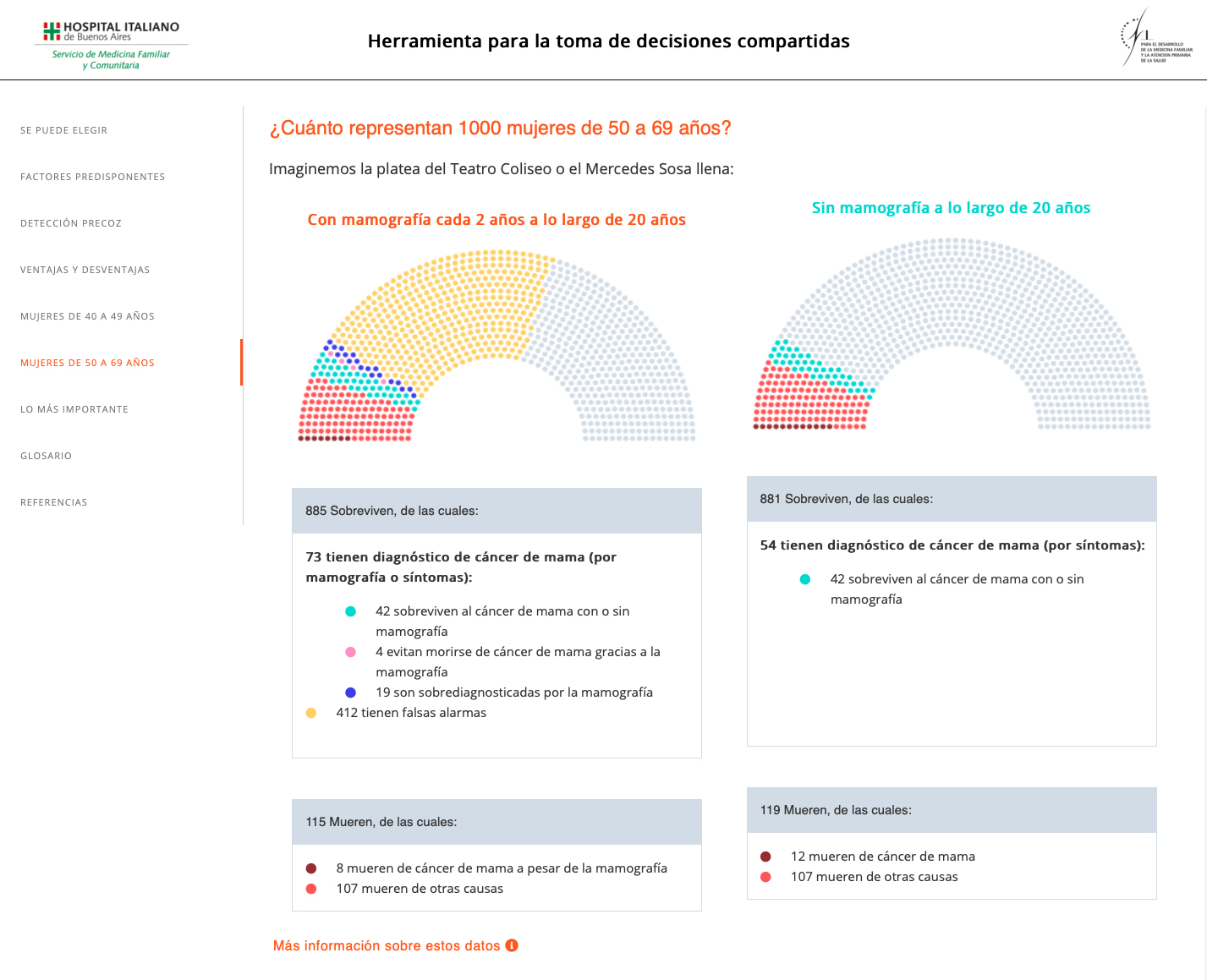

Risk graphic display used in the decision aid

Alpha testing

We collected 22 responses, 11 from doctors and 11 from patients (see Table 1). Overall, patients and doctors agreed that the content and design were appropriate, that it was a useful and applicable tool in their context and that they were motivated to use it. According to patients and physicians, the mean score was 4.1 and 4.2 on a scale from 1 to 5 (5 being "strongly agree"). The majority of patients and doctors agreed that the information in the decision aid reflected important aspects and balanced views about breast cancer screening, that it was clearly presented and that it helped to identify what was most important for patients when making a decision. All physicians agreed the tool was relevant for them and felt confident they could implement it in their practice.

All except one patient agreed that the tool addressed their need to know more about mammography or their health. This person suggested displaying more “aggressive” images about risk factors so people would take them seriously. We decided not to follow this advice because we thought that would confer a biased and judgmental opinion towards an option and modifiable risk factors, and does not embrace a diversity of choice. It does not align with the principles of shared decision making or patient-centred care. Two physicians did not agree that the language was adapted to their patients' knowledge, and we changed the content removing medical jargon. One physician was hesitant (nor agree or disagree), and one did not agree that the decision aid was easy to navigate and that it would be appropriate for use during a consultation. In response to this feedback, we rephrased the navigation instructions and we developed a tutorial showing how to use the decision aid and navigate the website. Also, we summarized the written content and included more interactive features (e.g. flashcards for the risk factors section) to reduce the cognitive load.

Full details about the quantitative results of the survey can be found in the supplementary materials.

International Patient Decision Aid Standards criteria checklist

The quality of the decision aid was tested against the 74-item International Patient Decision Aid Standards checklist [33

Discussion

Summary of the main results

We describe a systematic approach for developing a web-based decision aid to support physicians and women to make decisions during the clinical encounter about whether to participate in breast cancer screening. To our knowledge, this is the first decision aid developed in Argentina [20

Results in the context of published literature

When exploring women’s information needs concerning this decision, we found similar results as previous research in our setting: mammograms are being overused for screening purposes (women and some physicians mention starting screening earlier or at shorter intervals), there is a common belief that this practice is a mandate more than a choice, and the information about its harms is neglected [15,19,34

Our decision aid is aimed at women with an average risk of breast cancer, excluding women with major risk factors. However, we can find different baseline breast cancer risk in women of the same age group, i.e., women with no risk factors and women with minor risk factors such as obesity or nulliparity, who could benefit more from the relative reduction in the risk of dying from breast cancer. An accurate risk assessment is a crucial feature in a decision aid[36

Strengths and weaknesses

As part of the iterative process in designing our decision aid, we initially explored the information needs of patients that were 50 to 70 years old. Still, later on, we also decided to include 40 to 50-year-old women. Hence, the information needs of women in this age group might be underrepresented in this study. However, our findings were similar to previous studies in our setting, including this group of women[15

As for strengths, our tool was fully developed and customised for our patient population, designed based on the needs of our end-users, and written in Spanish. There are few decision-aids in Spanish and fewer developed in low and middle-income countries (LMICs)[20

Implications for practice and future research

This web-based decision aid (

Conclusions

We developed the first decision aid in our region and language to assist women in their conversations with their physicians when deciding on breast cancer screening with the input of the perspective of their end-users and informed by the best available evidence. Future research will assess the effectiveness of improving shared decision making and the transferability to other contexts.