Estudios originales

← vista completaPublicado el 15 de mayo de 2025 | http://doi.org/10.5867/medwave.2025.04.3013

Gestión menstrual e impacto de la intensidad de dismenorrea primaria en la calidad de vida: estudio transversal en mujeres chilenas

Menstrual management and the impact of primary dysmenorrhea intensity on quality of life: A cross-sectional study in Chilean women

Abstract

Introduction Primary dysmenorrhea is defined as pain during the menstrual cycle, recurrent cramping type in the absence of an identifiable cause. It can negatively affect the quality of life of those who suffer from it. The objective is to determine the association between pain intensity in primary dysmenorrhea and the impact on quality of life related to menstrual health, presenteeism, and sexual function in adult Chilean women.

Methods Cross-sectional observational study. A sample of 392 women with painful menstruation in the last six months. A self-reported survey was distributed on social media between January and June 2024, consisting of sociodemographic questions, pain intensity and perception, the EQ5D-3L quality of life questionnaire, the Stanford Presenteeism Scale, and the Women's Sexual Function Questionnaire adapted to the study.

Results The mean age was 29.2 +/- 8.2 years, and the mean pain intensity was 6.7 +/- 2.04 points. High pain intensity was associated with greater impairment. Those with severe or extreme pain experienced a significant impact on their quality of life related to menstrual health. Among the compromised aspects, the most notable were the performance of usual activities (OR 9.99), lower work performance (lack of concentration), and decreased social activities. The most common mitigation measures used were local heat (96.7%), herbal teas (63.5%), and medication (90%).

Conclusions Dysmenorrhea impacts different dimensions of quality of life. Despite its high prevalence, it is often underestimated, and women often normalize pain by employing various methods to mitigate it. The concept of menstrual health is a subjective and multidimensional experience. The results suggest the importance of comprehensively updating the management of dysmenorrhea and incorporating new studies on economic evaluation, prevalence, and self-image to delve deeper into the subject.

Main messages

- There is little national evidence regarding quality of life in women with dysmenorrhea, which limits informed clinical and public policy decision-making.

- An innovative approach is proposed that incorporates health-related quality of life, presenteeism, and sexual function, which are absent in previous studies.

- Dismenorrhea was found to affect multiple dimensions of quality of life in women who suffer from it, and it is an underdiagnosed clinical condition that leads women to use coping strategies, which are sometimes unregulated.

- The research has limitations, such as non-probabilistic sampling and information bias resulting from an online survey, but it provides useful findings for future research and interventions.

Introduction

Menstrual health is a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being. It is not merely the absence of disease or infirmity related to the menstrual cycle. This includes access to accurate information and education about menstrual management, as well as the ability to manage pain and menstrual hygiene safely and with dignity [1].

One of the most common menstrual health problems experienced by women of reproductive age is primary dysmenorrhea. This is defined as recurrent cramp-like pain during the menstrual cycle, in the absence of an identifiable pelvic cause. The pain interferes with daily activities and negatively affects a woman’s quality of life [2,3,4].

Its prevalence varies due to its multidimensional nature, approach, sample selection, and methodological designs in different studies on dysmenorrhea. It is estimated that it affects between 45% and 91% of menstruating women, and 2% to 29% experience severe pain [5,6,7]. Despite the high percentages, it is underdiagnosed, inadequately treated, or normalized [5].

Physiopathologically, it is characterized by an alteration in prostaglandin F2α (PGF2α) and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) levels during endometrial shedding. This causes uterine hypercontractility, restricts blood flow, and leads to the production of anaerobic metabolites, uterine muscle ischemia, and hypoxia, which subsequently stimulate pain receptors [5,8]. Its perception results from multiple dynamic mechanisms of the central and peripheral nervous systems, which inhibit or facilitate nociceptive stimuli and responses [9].

The intensity and duration of pain can vary significantly among women, beginning between 48 and 72 hours before menstruation and lasting up to three days. The first episode may occur between 6 and 24 months after menarche, increasing in intensity during adolescence. This highlights the importance of addressing this condition in its early stages [5,8,10]. The average intensity of menstrual pain is approximately 6 points on a visual analog scale (VAS), and it is associated with other symptoms such as headache, fatigue, digestive symptoms, musculoskeletal pain, abdominal distension, and sleep disorders, among others [10,11,12].

Because of its physical symptoms, dysmenorrhea affects women’s overall quality of life. On the one hand, it alters health-related quality of life, especially regarding mobility and usual activities [10,11,13]. In addition, it impacts women’s direct costs in terms of menstrual management and indirect costs by inducing a decrease in academic performance and work efficiency due to absenteeism [1,14].

We consider health-related quality of life as an individual’s perception of how their health status affects their daily functioning, ability to maintain independence, and physical, psychological, and social well-being within their environment [13,15].

Presenteeism is understood as workers being physically present at their workplace, even though they have some unfavorable medical condition that would typically require rest and absence from work. This decreases their performance, reducing productivity [16,17].

Studies on the quality of life in adult women with dysmenorrhea are a neglected topic in women’s health. As stated by the United Nations (UN), due to “persistent harmful sociocultural norms such as stigma, misconceptions, and taboos surrounding menstruation, women and girls continue to experience exclusion and discrimination” [14]. For these reasons, the following study is relevant in attempting to answer the question in the Chilean context: What is the impact of menstrual pain intensity on the quality of life of Chilean adult women? Its objective is to determine the association between pain intensity in primary dysmenorrhea and the impact on quality of life related to menstrual health, presenteeism, and sexual function in this segment of the population.

In addition to determining the altered dimensions of quality of life due to dysmenorrhea, we seek to describe the concomitant symptoms and menstrual management of these women.

Methods

An observational, cross-sectional, analytical study was conducted following STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines for observational studies [18]. The Ethics Committee of Diego Portales University approved the research protocol.

Sample selection

Women aged 18 to 50 years, born and residing in Chile, who had experienced menstrual pain in the last six months, were included.

Those who reported pelvic trauma, endometriosis, or amenorrhea in the last six months and users of copper intrauterine devices were excluded. Recruitment was done using non-probability convenience sampling through social networks (LinkedIn, Facebook, Instagram) and women’s forums between January and June 2024. After applying exclusion criteria, the final sample size was 392 participants. The findings should be interpreted cautiously due to the selection bias inherent in the sample design [19].

Data collection

A survey was developed with sociodemographic questions, pain intensity using a visual analog scale, perception of menstrual pain, the generic quality of life questionnaire European Quality of Life 5 Dimensions 3 Level Version (EQ5D-3L, version validated in Chile) [20,21], the Stanford Presenteeism Scale (SPS-6) [22], and some items from the Changes in Sexual Functioning Questionnaire short-form (CSFQ-14) [23], excluding those related to lubrication due to menstruation.

To ensure the reliability of the data, the SPS-6 and CSFQ-14 questionnaires, which had not been previously validated in the general Chilean population, were adapted and subjected to semantic validation through a pilot study with 10 women with characteristics similar to those of the sample, who were not gynecological health professionals. This allowed for minor adjustments in wording, spelling, and punctuation. The questionnaire showed high internal consistency (Cronbach’s α of 0.89) and an average response time of 25 minutes.

The content was evaluated by three experienced professionals in women’s health, who were provided with a matrix that assessed semantics, clarity, relevance, consistency, and appropriateness. The experts' credentials are as follows:

-

E.1: Academic at an accredited Chilean university, master’s degree in sexuality, director of a sexuality institute, and member of national and international sexuality societies.

-

E.2: Academic and director of an accredited Chilean university, member of the scientific committee of an international women’s health society.

-

E.3: Specialist in menstrual health and sexualities, advisor on menstrual care management, and member of the board of directors of an institution dedicated to women’s health.

An Aiken V score between 0.83 and 1 was obtained, indicating high agreement among the experts. Based on their suggestions, questions about menstrual management were added.

Finally, the questionnaire was distributed via self-reporting on Google Forms between January and June 2024. The first page explained the purpose of the online survey and presented the digital informed consent form. This included confirmation of the women’s willingness to participate, ensuring the confidentiality of sensitive data by anonymizing it.

Variables

Sociodemographic variables

The sample description included age, gender, sexual orientation, sexual partner in the last six months, level of education, employment status, region of residence, and habits (tobacco, alcohol, and drug use).

Health insurance was also included, due to the mixed nature of the health system. This consists of four categories in the public system or National Health Fund (FONASA), designated by letters A for the lowest income and D for the highest income, and one category in the private system or Health Insurance Institutions (ISAPRE), whose membership correlates with income quintile distribution. In addition, a smaller percentage of the population is served by the armed forces and law enforcement agencies' systems. For this reason, the groups within the health insurance system in Chile are considered a good approximation of the economic income of their users [24]. Responses were classified according to the category to which they belonged in the six alternatives.

Dysmenorrhea variables

Perception of menstrual pain: The person was asked to rate their perception of premenstrual pain on days 1 to 2 and 3 to 4 of the cycle, using a Likert scale with five categories: none, mild, moderate, severe, and extreme.

Overall intensity of perceived menstrual pain: using a visual analog scale numbered 1 to 10, the person was asked to select the level that best represented the intensity of the symptom during the menstrual cycle, where 0 is no pain and 10 is the highest intensity [25]. To facilitate analysis, the obtained scores were grouped into two qualitative categories: mild to moderate pain (range 1 to 6 points) and severe to extreme pain (range 7 to 10 points).

Menstrual management: all the elements that women and menstruating people need to live their menstruation to the fullest [1,12,26]. The responses were grouped into contraceptive methods, menstrual hygiene, and pharmacological and non-pharmacological pain management strategies.

Concomitant symptoms: symptoms that accompany menstrual pain [10]. Respondents were asked to select the options representing users from a symptom list.

Quality of life variables

Rest: Volunteers were asked to assess their perception of how their usual rest was affected compared to the period without menstruation. Rest was rated on a five-point scale. Responses were then grouped into three levels: low/none, moderate, and considerable/a lot.

Menstrual health-related quality of life: This was assessed using descriptive questions from the generic EQ-5D version 3L questionnaire. This contains five health dimensions: mobility, personal care, usual activities, anxiety/depression, and pain/discomfort (only discomfort was considered for the study), with three levels in each dimension according to the degree of impairment [20,21].

This instrument has been adapted and validated in the general population and groups of people with specific Chilean pathologies. It takes approximately 2 to 3 minutes to complete [20,27].

Presenteeism: measured using the SPS-6 instrument, which considers two dimensions. The first relates to the efficiency of completing work despite the clinical situation (questions 2, 5, and 6), with responses scored from 1 to 5. The second dimension relates to avoiding distraction (questions 1, 3, and 4), with reactions scored inversely proportional to each other. The total score ranges from 6 to 30 points, with higher scores indicating a lower level of presenteeism. This means perceiving a greater ability to concentrate and perform work despite health problems [22,23]. Respondents were asked how much they agreed with the statement on a five-point Likert scale:

For the analysis, the responses were grouped into three levels.

Social activities: Volunteers were asked to evaluate their perception of how social activities were affected compared to the period without menstruation for family members/friends and work/study colleagues, rating it in five categories. The responses were then grouped into three levels: low/none, moderate, and significant/much.

Sexual function: a multidimensional concept that includes physical, psychological, emotional, and partner aspects of sexual activity [28]. It was measured using the CSFQ-14 tool [23], classifying the questions into three dimensions: arousal/desire, orgasm, and satisfaction. As with the previous variables, a five-category Likert scale was used, grouping the responses into three levels: never/rarely, sometimes, and always/almost always.

Statistical analysis

The sample was characterized using frequency tables and percentages. The mean and standard deviation were estimated for age, pain intensity according to the visual analog scale, and scores for each dimension of presenteeism.

The pain intensity variable was then categorized into two groups according to the reported score, with a score of 1 to 6 considered mild/moderate and 7 to 10 considered severe/extreme according to the visual analog scale. This is the group of interest. For comparisons between groups, the Student’s t-test was used to test for differences in means in the case of quantitative variables (age and presenteeism dimension scores). For categorical variables, Pearson’s chi-square test was applied.

Finally, the dimensions of the EQ5D-3L instrument and the subdimensions of the SPS-6 and CSFQ-14 scales were analyzed as dichotomous variables categorized according to the levels of impact. To do this, a value of 1 was assigned to the category with the greatest potential negative impact on pain intensity and 0 to the rest. Binary logistic regression models were applied to estimate the association between pain intensity and the impact on health-related quality of life, presenteeism, rest, social activities, and sexual function. The estimates were adjusted for type of health insurance, pharmacological and non-pharmacological strategies for pain relief use, and hormonal contraceptives. The results were expressed as odds ratios with their respective 95% confidence intervals. SPSS version 30.0 software was used for all analyses, and a p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

During the data collection period, 435 surveys were obtained. After applying the exclusion criteria, 392 were considered valid for the sample. The losses correspond to foreign women, women with myxomatosis, users of the TCu380-A intrauterine device, women diagnosed with endometriosis, and inconsistent surveys. Of the total sample, 80.9% were women living in metropolitan areas (Valparaíso, Biobío, and Metropolitan regions). The average age of the sample was 29.9 ± 8.2 years, ranging from 18 to 50 years, of which 87.5% were under 40. Of those surveyed, 98.2% identified as female and 1.8% identified as non-binary. At the time of the survey, 59.9% of the volunteers perceived their health status as good/very good. The characteristics of the sample are presented in Table 1.

The average age of women with mild/moderate overall pain intensity according to the visual analog scale was 28.5 +/- 7.5 years, and severe/extreme pain was 29.7 +/- 8.6 years, with a p value of 0.13 on the T-test for mean differences.

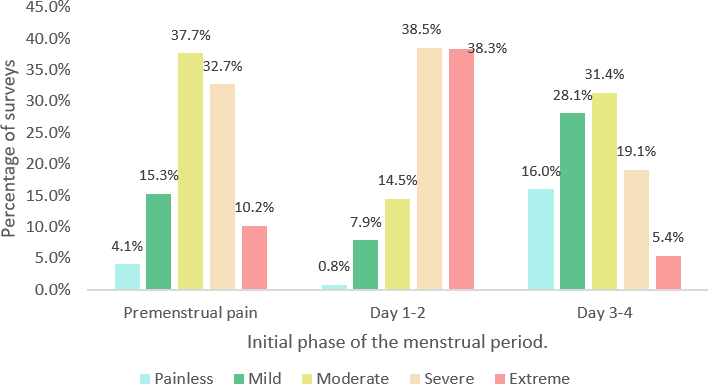

Seventy-five percent of respondents reported moderate/severe pain before menstruation, and 76.8% reported severe/extreme pain in the first two days, a distribution that can be seen in Figure 1. In addition, the average duration of menstruation was reported as 5.7 ± 2.7 days (2 to 20 days), with 39% reporting a regular amount of menstrual flow and 45.9% reporting heavy flow, predominantly on days 2 to 3.

Perception of pain in the initial phase of the menstrual period (n = 392).

Of the sample, 20.6% reported being always/almost always asked about their problems during routine gynecological checkups, and 26.8% indicated that they were sometimes asked. Of these, 27.4% were treated in the private (social security or private health institutions) and 72.6% in the public (National Health Fund). The use of hormonal contraceptives is a way to control the length of the cycle and the amount of flow. Menstrual management and pain relief methods can be seen in Table 2.

Menstrual health-related quality of life is significantly associated with the impact on the EQ5D-3L dimensions and menstrual pain intensity. The data show that women with severe/extreme pain have a higher concentration of responses in the categories with the greatest impact in each dimension (Table 3).

On the other hand, the sample has an overall SPS-6 score. The sample was 13.21 +/- 3.33 points (range 6 to 24 points), indicating a high level of presenteeism. In turn, the dimension of avoiding distraction had a mean and standard deviation of 7.75 +/- 3.07 points in those with mild/moderate pain; and 5.79 +/- 2.17 in those with severe/extreme pain, with a mean difference test with a p value < 0.001. On the other hand, for the dimension of task completion, the score was 6.66 +/- 1.43 points for the group of women with mild/moderate pain and 6.54 +/- 1.56 points for the group with severe/extreme pain, with a mean difference test of 0.43.

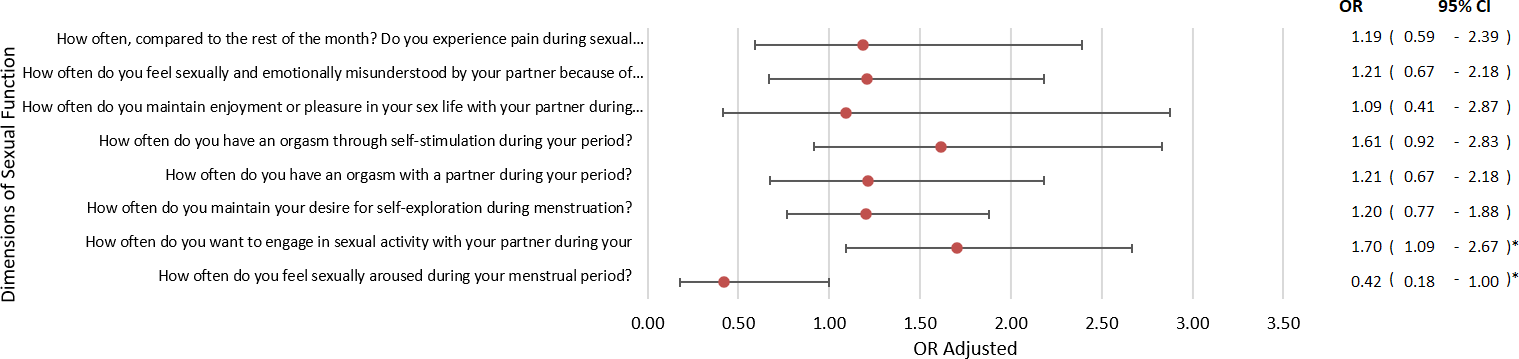

In terms of sexual function, a significant association was observed between pain intensity and the dimensions “lack of arousal”, “sexual desire with a partner”, and “achievement of orgasm both with a partner and through self-stimulation during the menstrual period”.

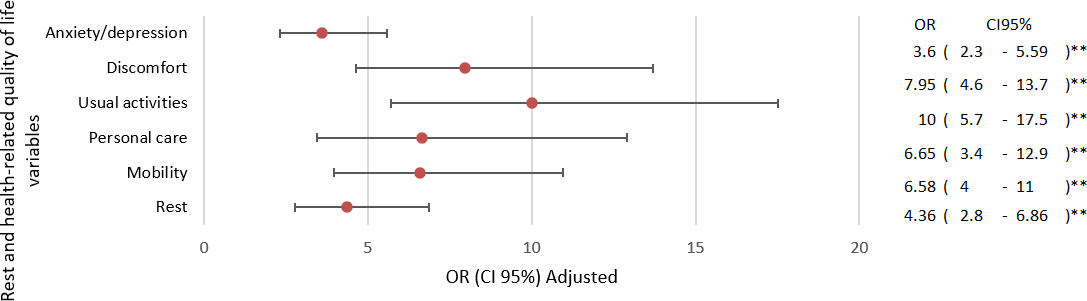

Table 3 shows the distribution of frequencies in the sample for each variable, grouped by the intensity of menstrual pain. Meanwhile, other results not shown in the table indicate that in 51.5% of the sample, dysmenorrhea has severely affected their activities with family and/or friends, and in 42% with coworkers. The odds ratios for these categories were 3.81 (2.45 to 5.92) and 4.4 (2.74 to 7.06), respectively, both significant (p value < 0.001). Consequently, menstrual health-related quality of life is impaired by dysmenorrhea. This is particularly noticeable in women with severe/extreme pain, who are more likely to experience severe impact compared to those with moderate/mild pain. In this context, usual activities are the most affected (Figure 2).

Comparison of severe/extreme pain in women with primary dysmenorrhea in Chile.

The odds ratio with a 95% confidence interval compares the odds of severe/extreme pain in women with the most affected categories of quality of life and rest dimensions with the odds of severe/moderate pain in the rest of the categories. The odds ratio was adjusted for health care, using mitigation measures (pharmacological and non-pharmacological) and hormonal contraception.

Source: Prepared by the authors.

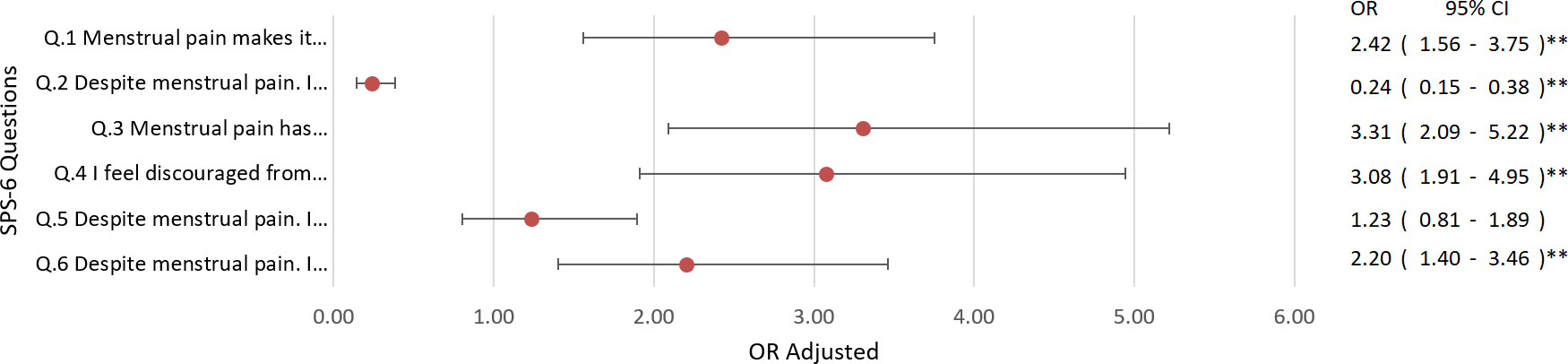

Women in the categories most affected by variables reflecting presenteeism have significantly higher odds of severe/moderate pain than those in the least affected categories as a whole (Figure 3). Overall, each dimension shows that these women have a greater impact on avoiding distraction than those with mild/moderate pain, with an odds ratio of 3.15 (1.99 to 4.98), with a p value < 0.001. On the other hand, in the “completing the task” dimension, the odds ratio was 0.80 (0.5 to 1.3) with a p value of 0.37.

Comparison of severe/extreme pain in the most affected dimensions of severe/moderate presenteeism compared to the rest of the categories.

Odds ratio with 95% confidence interval. The odds ratio was adjusted for health expectations, mitigation measures (pharmacological and non-pharmacological), and hormonal contraception.

Source: Prepared by the authors.

Finally, the odds of severe/extreme pain are 1.7 times higher in women who want to stay in their relationship than in those who do not (Figure 4).

Comparison of severe/extreme pain with the most affected categories of severe/moderate sexual function compared to the rest of the categories.

Odds ratio with 95% confidence interval. The odds ratio was adjusted for health status, mitigation measures (pharmacological and non-pharmacological), and hormonal contraception.

Source: Prepared by the authors.

Discussion

Our findings emphasize the negative impact of dysmenorrhea, observing a significant association between the level of perceived pain and the deterioration of different dimensions of women’s quality of life during the menstrual cycle. Thus, their physical and psychological health is affected. In addition, they are accompanied by various reported symptoms such as headache (56.6%), lower back pain (70.4%), and mood swings (79.6%), which add to this impact.

Menstrual management will depend on cultural aspects, accessibility in the country, and the information available [1]. Regarding how to cope with dysmenorrhea, 90% of our sample reported using some medication to relieve pain. Likewise, 87.73% reported non-pharmacological measures.

Of the sample, 57.9% reported severe/extreme pain during the first two days, and 42.1% reported the most severe pain. This reveals that they were 10 times more likely to be severely affected in their ability to perform usual activities compared to those with mild/moderate pain. Of the women with severe/extreme pain, 55.9% reported having to stay in bed, and 57.7% were unable to perform their usual tasks. In a mixed study by Chen [29], some women reported being unable to sit, walk, or stand when they had symptoms of dysmenorrhea. Others said they could not leave the house and remained in bed [29].

In terms of psychological impact, women with high levels of distress or depression are 3.6 times more likely (95% confidence interval: 2.3 to 5.59) to experience severe/extreme pain than those without such levels of distress or depression. In line with these results, the meta-analysis conducted by Rogers (2018) on dysmenorrhea and psychological stress reports that there is a significant association between higher levels of depressive symptoms, anxiety, and overall psychological distress and greater severity of dysmenorrhea [30].

On the other hand, a higher overall level of presenteeism is associated with greater pain intensity, especially in terms of concentration. Our results are consistent with those of Ortiz [31] in healthcare students in Mexico, where 78.7% reported impaired concentration and 69% reported impaired performance [31]. Cook (2023), in a sample of female workers in the European Union, reported a significant association between the severity of menstrual pain and presenteeism [32]. In addition, he reports that informing one’s superior about one’s health status is linked to a lower probability of presenteeism. A study of women aged 15 to 45 in the Netherlands found an average of 1.3 days of absenteeism per year and a loss of productivity due to presenteeism of 23.2 days per year on average [33]. In our study, 41.85% of women with severe/extreme pain reported a decrease in sexual desire, and 11.45% reported difficulty achieving orgasm with their partner. In addition, 10.57% of them reported dyspareunia. Hjorth [34] reported a decrease in sexual desire in 22.3% of his sample, dyspareunia in 9.8%, and difficulty achieving orgasm in 12.3% [34].

As a strength, this study contributes to a nuanced understanding of dysmenorrhea and identifies areas ripe for further research. The data provided are relevant in highlighting the multidimensional impact of this highly prevalent but under-addressed condition. The inclusion of women over 40 years of age, who are even more invisible in consultations on menstrual health issues, emphasizes the comprehensive and gender-sensitive approach to clinical care. This is particularly relevant when health service providers are male-led and biased toward a biomedical rather than a biopsychosocial perspective. We hope to provide valuable information for healthcare providers, society, and decision-makers in line with the Sustainable Development Goals, especially Goal 3 on well-being and Goal 5 on gender equality [1]. These refer to ending menstrual poverty, as “poor menstrual health and hygiene undermine the fundamental rights of women, girls, and people who menstruate, such as the right to work and go to school” [35].

Within the limitations of this study are the lack of validation in Chile of the Stanford Presenteeism Scale and the Sexual Functioning Questionnaire. Added to this is an online survey, which may have led to sample selection bias due to self-reporting and the study subjects' access to the internet. The non-probabilistic nature of the sample limits the generalizability of the findings, as they cannot be extrapolated to the total population. Finally, other variables that could be of interest were not included in the sexual function dimension, such as intensity, duration of desire and arousal, self-confidence, and perception of orgasm, among others. This made it difficult to compare between groups.

Conclusions

It is necessary to raise awareness and recognize the impact of dysmenorrhea on the lives of adult women to take measures to address it comprehensively. This includes implementing gender- and rights-based public and labor policies that recognize and accommodate the needs of women with dysmenorrhea, as well as implementing and developing more effective, patient-centered treatments. In this regard, health professionals should be aware of the impact of dysmenorrhea on women’s lives and be prepared to address it appropriately.

Given that the perception of pain, the concept of quality of life, presenteeism, and sexual function are subjective and multidimensional experiences, the results suggest the incorporation of new longitudinal studies that evaluate the long-term impacts of better menstrual management. Research should focus on socioeconomic and menstrual health outcomes, prevalence, self-image, and, in more detail, sexual function. This is in order to explore the topic further and identify new variables to monitor that will improve the overall quality of life of women suffering from dysmenorrhea.