Systematic reviews

← vista completaPublished on April 2, 2024 | http://doi.org/10.5867/medwave.2024.03.2800

Accreditation systems for midwifery training programs worldwide: A scoping review

Sistemas de acreditación de programas de formación en partería profesional en el mundo: una revisión de alcance

Abstract

Accreditation of midwifery training programs aims to improve the quality of midwifery education and care. The study aimed to diagnose the accreditation systems of midwifery programs worldwide, identifying characteristics, standards, and differences. According to Arksey and O'Malley’s framework, a scoping review was conducted by searching databases, grey literature, and accreditation system websites. A total of 2574 articles and 198 websites related to education accreditation were identified, selecting 47 that addressed midwifery programs. The results show that while a global accreditation system in midwifery from the International Confederation of Midwives exists, it has been scarcely used. There is considerable heterogeneity across accreditation systems, with higher-income countries having more robust and specific systems. In contrast, accreditation is less common in lower-income countries and often depends on international support. The diversity across accreditation systems reflects differing needs, resources, and cultural approaches. The need for standardization and global improvement of accreditation systems is highlighted. Strengthening the International Confederation of Midwives accreditation system as a global system, with standards adaptable to each country or region according to their local contexts, could be key to advancing the professionalization and recognition of midwifery worldwide.

Main messages

- Quality accreditation of training programs is key to ensuring the quality of midwifery education.

- There is a great diversity across midwifery accreditation systems worldwide, reflecting different political, social, and health contexts in each region.

- An accreditation system of the International Confederation of Midwives is highlighted, which could be adapted to the diverse contexts of midwifery education.

- A limitation of this study is that it is impossible to guarantee the inclusion of all the information available on accreditation systems for midwifery programs.

Introduction

Midwifery has been shown to significantly improve health indicators for women and newborns worldwide [1,2,3]. This highlights the importance of prioritizing investment in training these professionals in institutions that offer high-quality education [4], which is in line with the Sustainable Development Goals of the United Nations 2030 Agenda [5].

Three fundamental pillars have been identified to achieve a strong midwifery education: education, regulation, and association. Thus, quality midwifery education requires accreditation from institutional programs, professional practitioners, and trade associations [6]. These combined elements are the foundation of regulation, which enables professional midwives to practice autonomously and safely within their scope of practice [7].

Professional midwifery training programs vary in terms of duration and entry routes. There are programs ranging from three to five years, including those with direct entry to midwifery, as well as specialization programs for graduate nurses wishing to specialize in midwifery [8].

However, regardless of the type of training, such programs should meet minimum quality standards that reflect both the philosophy of midwifery and the needs of women and communities [9,10].

In response to the global call to increase the midwifery workforce [11], program accreditation is presented as a multidimensional strategy to verify that the offered professional training meets the standards [12,13] through formal recognition of essential skills and competencies of the professionals who complete the curriculum [14]. This regulatory mechanism aims to harmonize midwifery education with the sexual and reproductive health needs of the population, thus ensuring that the midwifery workforce is trained to provide high-quality care [8].

However, there is remarkable variability across countries in training programs and their corresponding accreditation systems [15,16], which do not always adequately reflect the needs of the population or their demographic, epidemiologic, and obstetric transitions [6]. Such alignment is crucial to ensure that the curriculum design is correctly adapted to meet the specific challenges of each healthcare system [17].

The International Confederation of Midwives (ICM) developed global standards for midwifery education to promote standardization in the accreditation process of midwifery education. These standards included categories such as program governance, faculty, students, curriculum, and resources. These categories provide a basis for making the implicit explicit, translated into competencies, achievements, and skills applicable to the training of these professionals [7,18,19]. However, these standards are generally unknown by program managers and teachers, revealing the need for them to be more widely disseminated and implemented [19,20].

In addition, there is little information on the accreditation systems available for evaluating midwifery training programs. This is demonstrated by the fact that, out of 175 countries that offer programs in this area, 14% lack information on the accreditation of the corresponding institutions or programs [8].

The general objective of this study was to diagnose the accreditation systems available for midwifery education programs, as well as their characteristics and applicability. The three specific objectives were:

-

To map and characterize the main accreditation systems for professional midwifery education programs.

-

Determine the dimensions or standards used.

-

To identify differences across midwifery accreditation systems.

Methods

This is a scoping review, understood as an exploratory research design that aims to investigate existing information on a topic [21] and inform the state of research and policy [22]. In this review, the methodology was based on Hilary Arksey and Lisa O'Malley’s framework [23], applying five of its six steps:

-

Identify the research question.

-

Identify relevant studies.

-

Selection of studies.

-

Recording the data.

-

Collate, summarize, and report results.

Research question

This review answers the question, "What are the characteristics, standards, and major differences across midwifery accreditation systems worldwide?

Identification of relevant studies

A search of education journals indexed in MEDLINE/PubMed, Scopus, SciELO, and Web of Science was conducted between September 2022 and September 2023 to cover the main areas of health and education. The inclusion and exclusion criteria are presented in Table 1.

Four search strategies were used to address the documents, carried out sequentially to contemplate the inclusion criteria:

-

Key informant consultation of the International Confederation of Midwives directory regarding relevant data that would facilitate the identification of accreditation documents in midwifery.

-

Database search, through selected keywords based on the components of the research question, for which specific search algorithms were designed. The keywords used in Spanish, English, and Portuguese included terms such as "accreditation", "certification", "professional midwifery", "professional training", "education", "midwives", "obstetricians" and "obstetrics". Additionally, the search was enriched with terms related to geographic mapping, initially prioritizing continents and then countries of the world.

-

The Google search aimed at identifying gray literature and articles not published in the databases considered a priori. The first two pages of results were reviewed, and the contents obtained from the following pages were considered irrelevant.

-

Targeted search on official midwifery websites available on the Internet, such as the International Confederation of Midwives and its midwifery associations [24].

Study selection and registration

The results obtained by the algorithms were exported to the bibliographic manager Mendeley Desktop, where duplicates were eliminated using the Check for Duplicates tool. The selected results were transferred to a Microsoft Excel table that allowed filtering and selection. Relevant documents and web pages were identified through a multi-stage selection process according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. In the first step, titles were screened. Subsequently, abstracts of articles that remained after the first step were screened. The last step involved full-text screening of all articles that passed the first and second phases. In the full-text selection, articles with insufficient information in the title and abstract to determine their relevance were also included. The same procedure was performed for web pages.

Two reviewers independently completed the multi-stage selection process, interacting with a third reviewer when needed. Before moving to each stage, disagreements were discussed until a consensus was reached.

Collation, summary, and report of results

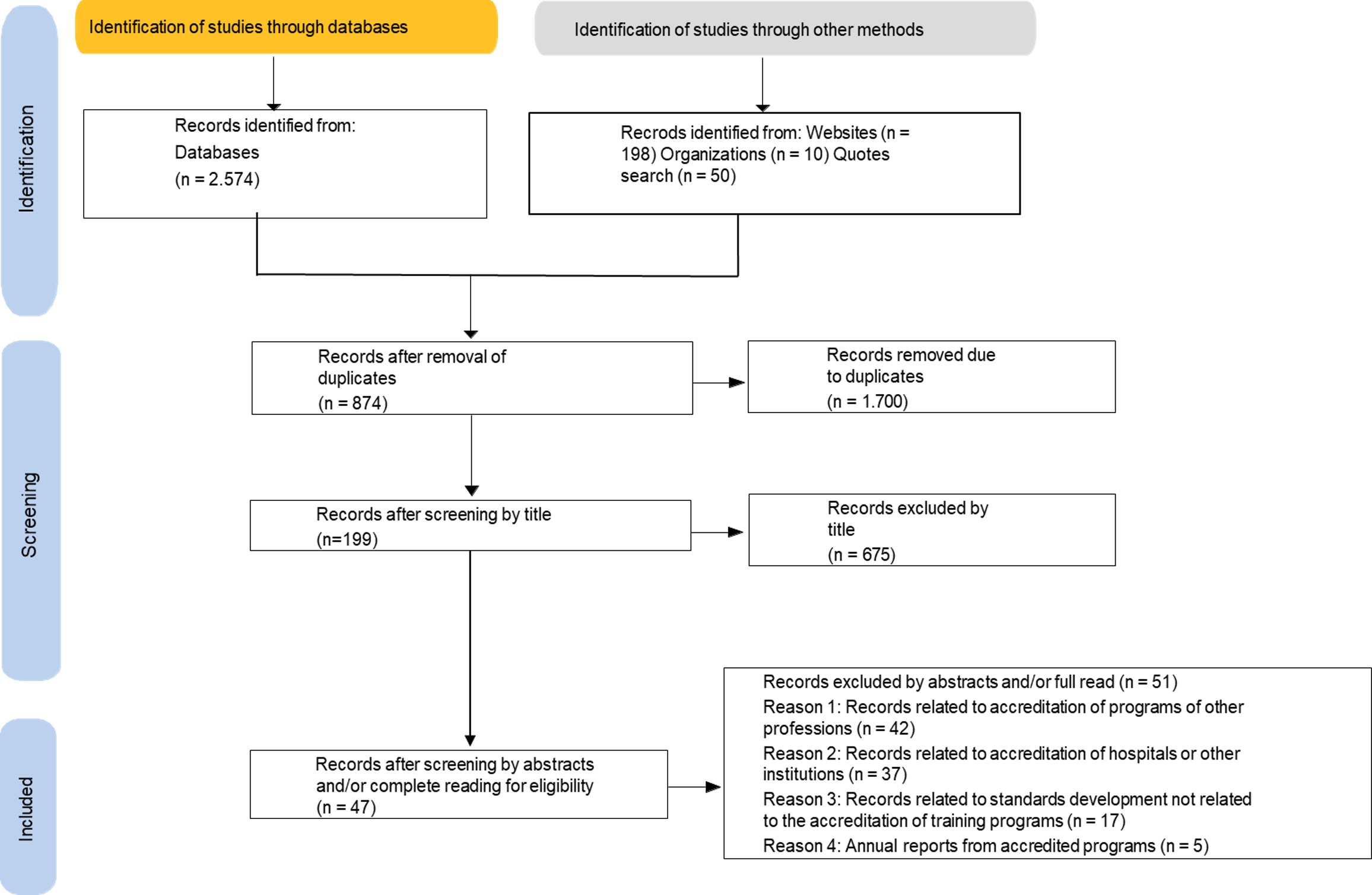

The results were presented using a mixed technique with tables and narrative descriptions, which allowed for synthesizing, ordering, and highlighting the information collected, addressing the research question clearly. This includes the presentation of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) diagram, which outlines the process of searching and selecting documents.

Results

The mechanism for selecting information and records can be seen in Figure 1.

Flow chart adapted from PRISMA, Haddaway et al., 2022 [25].

A total of 2574 articles and 198 web pages related to accreditation in education were identified, selecting 47 records that met the inclusion criteria and had no exclusion criteria.

Characterization of the included records

Of the 47 records included in the scoping review, 32% (n = 15) corresponded to an accreditation council or institution’s websites, 36% (n = 17) reported descriptions of accreditation systems or implementation processes, and 32% (n = 15) addressed standards.

Of the selected records, nine midwifery-specific accreditation systems were identified with complete information regarding their characteristics and standards. One is global [10,26], one is continental [27], and seven are specific systems adopted by six countries [28,29,30,31,32,33,34]. In addition, we describe systems that, without being specific to midwifery or lacking complete information, account for the accreditation of this area.

Mapping of accreditation systems for midwifery education programs worldwide

The Midwifery Education Accreditation Program [26] of the International Confederation of Midwives is the only program with a global scope and was created to assess whether midwifery education programs meet the global education standards set by the International Confederation of Midwives [20]. It has been piloted only in countries such as Comoros, Trinidad and Tobago, and Bangladesh [10,35,36].

In North America, Canada has the Accreditation Council under the Canadian Association for Midwifery Education [28]. This body is non-governmental and self-funded and focuses on ensuring the quality of midwifery education. Each Canadian province has its own regulatory college that defines standards for midwifery practice, and accreditation is critical to meeting these requirements.

In the United States, accreditation of midwifery programs is managed primarily through two non-governmental entities: the Accreditation Commission for Midwifery Education [29] for graduate midwifery nursing programs, and the Accreditation Council for Midwifery Education for direct-entry programs [30]. Both entities ensure that midwifery education programs in the United States meet rigorous standards, contributing to safety and competence in professional practice.

In Latin America and the Caribbean, training programs are evolving toward greater professionalization and standardization of midwifery, with efforts to improve the quality of education and the integration of traditional and modern approaches to maternal and neonatal care. However, no specific accreditation programs were identified for this area; they are mostly national accreditation systems for higher education entities with general quality educational standards [37,38].

In Oceania, midwifery accreditation systems in Australia and New Zealand are characterized by their rigorousness, attention to quality, and client safety, along with the development of professional practice autonomy [32,39,40,41]. The Australian Nursing and Midwifery Accreditation Council [31] accredits midwifery programs that meet specific standards required by the Nursing and Midwifery Board of Australia, which regulates professional practice. In addition, accredited educational institutions must be registered with the Quality and Standards in Higher Education Agency [42]. In New Zealand, the Midwifery Council accredits and regulates, focusing also on degree-level programs emphasizing clinical experience [32]. In both countries, accreditation emphasizes comprehensive training for midwives, reflecting the high value placed on this profession in the region’s healthcare system.

In the United Kingdom, accreditation was formerly carried out by the Royal College of Midwives [43]. However, it is now regulated by the Nursing and Midwifery Council, responsible for setting and maintaining standards for midwifery education and practice [44]. This accredits midwifery education programs offered by universities and other institutions through an external auditor [45], with a strong focus on patient safety and quality of care, regularly updating its standards to align with best healthcare practices.

In Europe, countries such as Spain, Germany, Sweden, France, and the Netherlands, while not having specific midwifery accreditation systems, those available have adjustments or criteria aligned with European regulations and adapted to the needs of professional midwifery [46,47]. This has allowed them to advance in the development of this profession [48].

In Africa, midwifery training and accreditation systems vary significantly between countries, reflecting the diversity of political, social, and health contexts throughout the continent. Many African countries have nurses with brief midwifery training. However, others are working to improve and standardize midwifery training with the support of international organizations such as the World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations Population Fund, according to the human resource training objectives for the region [11]. An example is Sierra Leone, which adapted its standards based on the WHO’s guidelines for evaluating the African region’s basic nursing and midwifery education and training programs [27,33]. Mali, for its part, used these guidelines verbatim [49]. Other African countries, such as Kenya [50] and South Africa [51], state that they have accreditation systems for their programs but do not specify mechanisms or standards.

In Asia, midwifery accreditation systems are evolving, with trends towards greater standardization and professionalization, although they still face challenges related to quality, accessibility, and recognition within healthcare systems. Thus, countries such as Afghanistan and Indonesia, which have implemented their own midwifery accreditation systems, stand out for having specific systems. Afghanistan has the Nursing and Midwifery Education Accreditation Board of Afghanistan [52] and the Afghan Council of Midwives and Nurses [53]. Since 2007, a national accreditation program has been in place that includes educational standards, assessment tools, technical support, and an official recognition system [54]. This program was evaluated using a sample of twenty-nine midwifery programs from public and private institutions. The results showed challenges in program homologation, clinical fields, and student treatment, with a strong political and gender component [55]. In Indonesia, an accreditation system was implemented by the Indonesian Accreditation Agency for Higher Health Education [34], which has established standards for the accreditation of midwifery programs in the country [3]. Other Asian countries have developed basic midwifery accreditation systems tailored to their public health and cultural contexts. Like other African countries, along with Pakistan, Japan, India, Thailand, Malaysia, and the Philippines, nursing councils and the Philippines nursing councils claim to accredit their programs but do not provide explicit mechanisms or standards.

On the other hand, the literature reflects the efforts of other Asian countries to introduce accreditation systems, such as Iran, where standards for clinical education in midwifery have been developed [56], and Bangladesh, where accreditation diagnosis has been carried out and instruments for national application have been proposed and evaluated [35,36,57]. However, no official midwifery accreditation system has been implemented in the above cases.

Characteristics of accreditation systems for midwifery education programs worldwide

Regarding the main characteristics of the accreditation systems, this review considers the declared costs, duration of accreditation, and post-accreditation follow-up processes of the systems that make them explicit (Table 2).

The Midwifery Education Accreditation Program of the International Confederation of Midwives is distinguished by its reserved method. It does not specify costs or the duration of its accreditation, suggesting a comprehensive initial assessment model and a permanent accreditation without specifying periodic reviews. In contrast, Australia, through its Australian Nursing and Midwifery Accreditation Council, details the associated costs, including an initial fee and annual maintenance fees based on the number of campuses and implementing annual monitoring to oversee significant program changes.

In the United States, the Accreditation Commission for Midwifery Education and the Accreditation Council for Midwifery Education for direct entry programs also provide a detailed description of the costs associated with accreditation, but with a structure that provides for initial evaluations, annual maintenance, and reassessments at defined cycles.

On the other hand, the United Kingdom, New Zealand, and Sierra Leone present an approach in which accreditation costs are not explicitly specified, suggesting that accreditation is handled by external entities or in partnership with the government and treated as a mandatory requirement rather than a fee-based service.

The systems used in Africa and Indonesia articulate accreditation costs and introduce accreditation cycles based on meeting standards and making improvements.

Finally, Canada, without declaring costs, establishes a seven-year accreditation period, with the possibility of adjusting this term according to the accreditation commission’s evaluations. This flexibility recognizes the diverse needs and situations of educational institutions. This spectrum of accreditation systems reflects the complexity and variety of strategies adopted globally to assure and promote quality in midwifery education.

Accreditation standards in midwifery programs

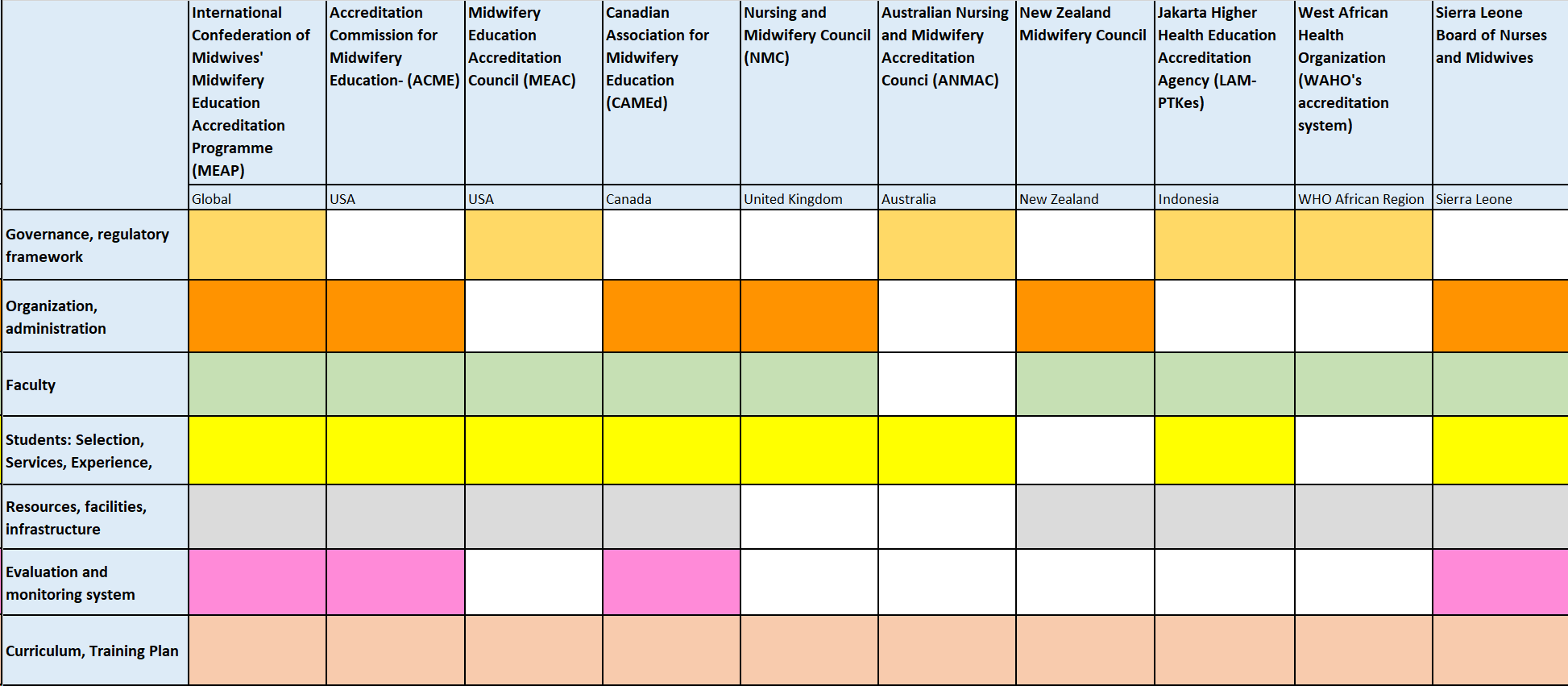

The main dimensions and standards used in identified midwifery accreditation systems not audited by external agencies have been identified and analyzed. Seven dimensions (governance and regulatory framework; organization and administration; faculty, faculty or teaching staff; students; resources and infrastructure; assessment and monitoring systems; and curriculum) are considered in this review, aligned with the five global standards of the International Confederation of Midwives for midwifery education (program governance, faculty, students, curriculum, and resources) [19]. These dimensions represent general assessment categories, while the standards are the criteria used to measure compliance with these, which are difficult to cite in their entirety given their large amount. Both are essential components in academic accreditation processes, and their combination allows for a complete and detailed evaluation of educational quality.

The accreditation dimensions illustrated in Figure 2 cover more than a hundred standards considered in their entirety by the accreditation system of the International Confederation of Midwives [12,19]. The other analyzed systems cover at least three of them, with the dimension that evaluates the curriculum being the only one considered by all [26,28,29,30,31,32,33,58]. This dimension is followed by the one related to resources and infrastructure and the one focused on faculty evaluation.

Dimensions comparison of midwifery program accreditation systems of countries or systems with published standards.

Some systems that do not contemplate all the dimensions analyzed in Figure 2 present others that have emanated from their realities. Thus, the Accreditation Council for Midwifery Education system for direct entry programs in the United States considers a dimension with standards focused on user feedback, highlighting the importance of user experience and satisfaction [30]. Similarly, the Australian system contemplates a specific dimension of user safety, positioning its quality focus on the student body and the people who will receive care [31]. In turn, moving towards considering quality elements that are not exclusively technical, the Nursing and Midwifery Council of the United Kingdom incorporates a learning culture dimension [44]. The WHO Africa standards system [27], used by Mali, considers an environment and partnership dimension. Finally, the New Zealand system transversally includes the interculturality of the context and of the program itself in its dimensions [32].

Regarding the standards implicit in the dimensions, the systems of Canada [28], the United States [29], Australia [31,57], and New Zealand [32] stand out, which have highlighted aspects related to the cultural security of native communities and the ethical and open learning culture [59,60,61,62,63].

This shows that considering dimensions and accreditation standards in midwifery may be subject to local needs relevant to diverse legal, political, epidemiological, demographic, and territorial contexts that emphasize some dimensions over others.

Differences in midwifery program accreditation systems

There are differences among midwifery accreditation systems worldwide.

Table 3 identifies four types of midwifery program accreditation systems. The first includes institutional accreditation systems without a specific system for midwifery programs [37,38,64]. Other systems adapt the evaluation to midwifery programs, although they do not have a specific system. On the other hand, some systems do not facilitate midwifery accreditation but have access to international systems such as the International Confederation of Midwives or other accreditation systems supported by the World Health Organization [33,49,65]. Finally, there are accreditation systems specific to midwifery programs. These establish alliances with the respective trade associations, facilitating the accreditation of programs and the certification of professional practice [28,29,31,32].

Countries in the northern hemisphere, such as the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom, have their own specific accreditation systems certifying professional practice. In contrast, countries in the southern hemisphere, except for Australia and New Zealand, either lack specific accreditation systems for midwifery or depend on the support of international organizations to carry it out [18,36].

According to the World Bank income level classification [66] and the presence and nature of midwifery accreditation systems, it can be identified that while high-income countries such as the United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, United Kingdom, and others in Europe have midwifery-specific accreditation systems or have adapted their assessment systems to suit midwifery programs, middle- and low-income countries such as Sierra Leone, Afghanistan and other African and Latin American nations rely on support from non-governmental organizations or lack accreditation systems of their own. This variability by income level reflects differences in the availability of resources among countries and underscores inequalities in quality assurance and regulation of midwifery education.

Discussion

The results of this scoping review demonstrate that midwifery accreditation systems are heterogeneous worldwide, in line with previously published research [15]. In regions with well-established accreditation systems, midwives often enjoy greater recognition and autonomy, resulting in an integrated and respected practice within the healthcare system [4]. However, in many countries, midwifery still struggles to gain recognition and autonomy, directly impacting the quality of education and practice [1,67].

The observed difference in midwifery accreditation systems worldwide is consistent with the State of the World Midwifery report. This report states that, although progress in midwifery education has been observed, this progress has not been evenly distributed [8]. In line with the above, the literature describes considerable efforts to establish optimal standards to ensure quality in the education of midwives [68,69,70,71]. However, differences persist in training criteria and in the assessment of professional competencies, which may intensify inequalities related to development, as well as to the needs and priorities of each country and region [48]. Such differences represent a challenge to ensure competent professional practice worldwide.

Although global standards for midwifery education are described and considered by the International Confederation of Midwives in its Midwifery Education Accreditation Program [26], their application across the world has been limited, posing a major challenge to the recognition, advancement, and regulation of midwifery worldwide [6,8]. Failing this, a comparison of accreditation systems worldwide reveals a remarkable diversity in terms of geographic distribution, characteristics, and prioritized standards or dimensions. This reflects diverse conceptions of quality in midwifery training, whose variability could be linked, among other aspects, to the stage of obstetric transition in the contexts where the training programs are implemented [72,73]. This relationship corresponds with the different epidemiological and demographic phases influencing reproductive health indicators, such as maternal mortality and fertility rate. These indicators reflect the multiple challenges professional training faces in providing high-quality midwifery care [67]. Similar to the obstetric transition model, different levels of development exist across accreditation systems, which unevenly ensure the quality of professional training for those who will provide midwifery care. These systems are differentially adapted to the two main dimensions of quality as defined by WHO: provision of care and people’s satisfaction [74].

Challenges related to advanced transitions are being addressed in high-income countries with more robust and targeted midwifery accreditation systems. These challenges have focused their standards on ensuring people’s satisfaction, incorporating topics of interculturality, gender, and ethics in service delivery [39] beyond curricular structure, resources and infrastructure, and other aspects relevant to educational quality. In contrast, in low- and middle-income countries in the early stages of transition, where accreditation systems are not yet fully established or are not specific to midwifery, professional training focuses on reducing maternal and neonatal mortality [4,13,75]. In these, people’s satisfaction has not yet been integrated as a fundamental element in the accreditation processes since resources, infrastructure, and curricular aspects associated with training professional competencies to address basic maternal and perinatal indicators are prioritized in the accreditation standards [36].

Our results also encourage discussion on the need for improving together the processes of quality assurance of education, policies, and mechanisms for regulating the professional practice of midwives to avoid the dissociation that often exists between professional training, regulation of professional practice, and the care needs of the population [76]. In this regard, the evidence indicates that it is essential to advance not only in facilitating the acquisition of professional competencies and individual certification but also in developing policies that enhance professional practice after graduation from training programs [76,77,78].

Improving and standardizing existing midwifery accreditation systems and ensuring their application is adapted to diverse contexts is vital to training competent midwives and providing quality care [1,79].

This scoping review has certain limitations and biases, including selection bias due to reliance on specific databases and the focus on papers in English, Spanish, and Portuguese, which restricts the inclusion of papers in other languages. Although we have attempted to mitigate publication bias by including gray literature and consulting key informants and have sought to limit geographic bias through a broad search strategy, there is no guarantee that all midwifery accreditation systems available worldwide will be included.

Conclusions

Accreditation of midwifery programs carries a remarkable diversity, highlighting the complex interplay between countries' income levels, professional regulation, transitional stage, and quality of care challenges in midwifery. This diversity is not merely a matter of variation in educational practices but reflects how accreditation and regulatory structures are intrinsically connected to public health and education policies in each region. This review reveals that while some countries have significantly progressed in developing accreditation systems for midwifery programs, others face significant challenges. These challenges include adaptation to specific cultural and socioeconomic contexts and the scarcity of resources to develop appropriate accreditation systems. International collaboration, adapting global standards to local contexts, and supporting countries with limited resources can improve the quality and accessibility of midwifery education worldwide. Thus, strengthening the accreditation system of the International Confederation of Midwives, with standards adaptable to contexts, is proposed as a necessary strategy for strengthening midwifery from the pillars of education, partnership, and regulation.