Analysis

← vista completaPublished on May 28, 2014 | http://doi.org/10.5867/medwave.2014.04.5958

Challenges facing the finance reform of the health system in Chile

Desafíos para la reforma del financiamiento del sistema de salud en Chile

Abstract

Financing is one of the key functions of health systems, which includes the processes of revenue collection, fund pooling and acquisitions in order to ensure access to healthcare for the entire population. The article analyzes the financing model of the Chilean health system in terms of the first two processes, confirming low public spending on healthcare and high out-of-pocket expenditure, in addition to an appropriation of public resources by private insurers and providers. Insofar as pooling, there is lack of solidarity and risk sharing leading to segmentation of the population that is not consistent with the concept of social security, undermines equity and reduces system-wide efficiency. There is a pressing need to jumpstart reforms that address these issues. Treatments must be considered together with public health concerns and primary care in order to ensure the right to health of the entire population.

Introduction

Financing is one of the key functions of health systems, which according to the World Health Organization (WHO) definition is understood as the process of collecting revenues and placing them at the service of the system, in order to ensure access for the entire population both to public health services as well as individual care [1].

Financing systems fulfill three interrelated functions: revenue collection, related to the sources of financing for the system; fund pooling, to spread the financial risks among the entire population; and the use of funds to provide the services related to the payment mechanisms [1].

Each country chooses the financing model for their health system, through various combinations of the above mentioned functions. This configuration is not only determined by health needs, but essentially by sociopolitical tensions present on the national scene. In Chile, the entire history of the health system clearly shows how the political situation has set the stage for either progress or limitations in relation to the inequalities in healthcare and how at present ‒despite the diagnoses‒ a political consensus that would allow carrying out the required reforms has not been achieved. [2].

Within the context of the call made by the current government of Michelle Bachelet for putting together a commission to propose changes to health insurance systems, this article focuses on analyzing the financing model of the Chilean health system as a way to contribute to this discussion. For this analysis, the official figures with regard to health expenditure in Chile published by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and by Chilean institutions such as the National Health Fund and the Health Superintendence were reviewed. Articles published in scientific journals, analysis papers, and opinion articles available on the Internet were also consulted. The analysis focuses especially on the collection and pooling of funds, taking into account the principles of solidarity, equity, and efficiency as essential for an effective materialization of the right to the highest possible level of healthcare for the entire population.

Sources of financing

The supply of resources for financing a health system comes from various sources, which can be classified into three types: public financing from general taxation; social security contributions that are also public expenditure; and private household spending that can be made through private insurance or out-of-pocket payments [3]. In Chile there is a combination of all sources of financing, as can be seen below.

According to OECD data, in 2011 Chile assigned 7.4% of its gross domestic product (GDP) to health. In absolute figures, this represents 1,568 United States dollars (USD) per capita, below the 9.3% of GDP (or 3,339 USD per capita) spent on average by OECD countries [4]. According to National Health Fund data, total expenditure on health, including inter-institutional fiscal contributions and municipal contributions, was 7.6% of GDP for this same year.

In terms of public expenditure on health in 2011, the OECD points out that in Chile this was 46.9% of total expenditure [5], whereas the National Health Fund shows this contribution as being at 57.8% [6]. Nevertheless, in this public expenditure the National Health Fund considers resources coming from workers’ statutory contributions for health insurance ‒resources that although in theory are from a public source, in practice is not part of the moneys available for the entire system. Therefore, strictly speaking, they apply to private spending [7].

This transfer to the private sector means the State does not have these resources for financing the health system, namely those that come from the 16% highest-income population. As a result, almost half of all revenues under the social security concept are only available to those covered by health insurance institutions [7]. For example, revenues of health insurance institutions for this concept in 2011 were 1.9 million dollars (1% of GDP) and total resources collected through statutory contributions were 4.1 million dollars [6], [8].

Hence, public expenditure in 2011 was only 3.4% of GDP, which was 44.7% of total expenditure. This public expenditure percentage was far less than in OECD countries, for which the average is 72.2% [4]. The 70% public expenditure on health is the fiscal contribution derived from general taxation and 30% of health contribution revenues collected by the National Health Fund [6].

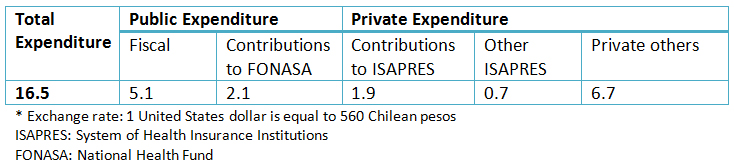

From another viewpoint, of total expenditure on health, 30% is fiscal contribution, 25% the statutory contributions collected by the National Health Fund and health insurance institutions, and the remaining 45% is private spending as such. Table 1 shows the distribution of total expenditure on health in Chile for 2011. The table was prepared based on data from the 2012 statistical bulletin of the National Health Fund and from information on the results of health insurance institutions by the Health Superintendence.

Full size

Full size When analyzing private expenditure for the same year 2011, 36.9% of total expenditure on health was out-of-pocket payments (65% of private spending when considering monthly contributions to health insurance institutions, and 80% when not accounting for them). This situation places the country among the highest percentages in this type of spending among OECD countries [5], [9]. Out-of-pocket payments are the health expenditure with the greatest impact on household budgets, and the most inequitable and least efficient source of financing. This spending can turn into a catastrophic event for families, causing them to fall below the poverty line, and hence it is a key factor to be taken into account when seeking healthcare [7], [10].

It is therefore possible to say that financing sources for the Chilean health system are mostly private and essentially derived from out-of-pocket payments [11], [12].

The fund pooling function

Fund pooling is the chief manner in which to equitably distribute risk among participants. In this quest for equity, a health system should not only ensure crossed subsidies from low-risk to high-risk individuals, but should also create crossed subsidies according to income [1]. In this way, there will be solidarity when access to healthcare services is independent of contributions to the system and people´s ability to make out-of-pocket payments [13].

As has already been mentioned, in the Chilean model there are two subsystems that carry out fund pooling: the National Health Fund, which acts as public insurance, and the health insurance institutions. The latter are private insurers that collect the statutory social security contributions from the highest income segment of the population (this analysis excludes the administration of work-related injury and disease insurance, as well as health systems for the armed forces). The system of health insurance institutions, which operates according to the private insurance logic, selects its subscribers according to their individual risk, discriminating individuals presumed as having greater health needs (senior citizens, women of child-bearing age, children, the chronically ill), charging differentiated premiums according to this risk over-and-above the statutory 7% [14].

In the health system in general, this has meant that there is a marked segmentation of the population based to their income. The public subsystem concentrates more than 80% of the population over the age of 70, and more than 70% of women of childbearing age, while their subscribers are mainly from the lowest income quintiles. On the other hand, in the private subsystem, subscribers are essentially from the highest income population and present lower health risks (young males) [1].

Thus, each beneficiary in the system of health insurance institutions has 47.5% more financing than a user of the public system in terms of health spending. Consequently, Chilean social security does not distribute risks among members of society, nor does it create crossed subsidies among different levels of income [1], [6].

Discussion

In Chile there is a low level of expenditure on health and a high level of out-of-pocket payments, in addition to a transfer of public resources to private insurers that do not operate in terms of solidarity or risk distribution. Predominant sources of financing are more individual rather than collective, which is contrary to the concept of social protection for health and its consideration as a right.

It is necessary to move toward a collective model of health financing that reduces out-of-pocket payments and increases public contributions as financing sources, as well as recovering the health contributions that are today transferred to the health insurance institutions and ensure crossed subsidies in terms of risk and income.

For Camilo Cid, the functional solution to the current system would be to have a single solidarity fund and an ample community premium to finance it, allowing equitable off-setting of risks. Health insurance institutions would retain the administration of these funds, but they would be obliged to accept everyone who requests to pay into the system, regardless of age, sex, or risk of illness [15].

This solution recovers the 7% statutory contributions for pooling in a single solidarity system that allows participation of multiple insurers and whose financing would be supplemented by the general taxation necessary to finance the contributions of those lacking resources [16]. The proposal, however, focuses on the conception of health as an individual issue, since there is no discussion of the financing mechanism for public health issues, nor is there any relation to the family and community health model which should be strengthened in primary healthcare. At present, subscribers to the health insurance institutions do not have access to this collective health approach, and neither does the financing proposal address this shortcoming.

Furthermore, the Cid et al proposal states each insurer should have a network of accredited providers, but that vertical integration of the system would not be permitted to avoid price manipulation and possible quality issues [16]. Nevertheless, there are many advantages in vertical integration for a health system: reduction of transaction costs, efficiency in resource allocation, and coordination effects, among others [17]. The difficulty arises when such vertical integration occurs within the context of the health market, since it prevents competition both in the provision of health services as well as insurance. It follows, hence, that the proposal consecrates the health market as “the way” for offering health to the population.

In addition, it is worth considering that the financing system should have a redistributive component to offset existing inequities in society, which implies the intervention should be progressive. The statutory 7% contribution for health works in practice as a labor tax, since dependent workers are obliged to pay (the obligation for independent workers starts in 2015) and excludes informal workers. Also, this tax has a ceiling of 4.92 indexation units known as Unidades de Fomento (208 USD), and which corresponds to a monthly wage of 70.3 Unidades de Fomento (2,980 USD) [16]. In this way, workers that earn more than this amount will pay less and less the more they earn, thereby making the contribution ‒having a single rate and a ceiling‒ in reality a regressive tax.

To the above it is necessary to include the fact that health insurance institutions that administrate the 7% statutory contribution are for-profit organizations and are ultimately profiting with public resources ‒which is ethically questionable as discussed in relation to the issue of education. Health insurance institutions are currently one of the most profitable businesses: net profits earned from January to September 2012 rose to 66 billion pesos, more than tripling earnings for the same period in the previous year [18].

Today in Chile a tax reform is under discussion, one which aims to capture available resources to ensure financing of permanent expenditure contemplated for social areas such as education and health. In this context it is feasible to think of a public financing model based on general taxation as a source of revenue, and which on account of its progressive nature would allow reducing the financial burden of families, and in a fund pooling system guarantee resource distribution in relation to health needs. This includes financing of public health, investment, and the primary healthcare model.

However, considering the current socio-political context, maintaining the social security system through statutory contributions implies developing a mechanism that allows the progressiveness of this tax. In terms of pooling, it is essential to develop a single fund to guarantee the distribution of risks and revenues. To administrate these resources, multi-insurance could only be considered through non-profit organizations. To this mechanism it is necessary to add financing through general taxation to cover public health issues as well as primary healthcare, to which the entire population should have access.

Lastly, it is urgently required to increase public expenditure on health as a percentage of GDP, in order to ensure that the amount of available resources covers the health needs of the country.

Conclusion

Chile has a health financing model that is not consistent with the values of solidarity, equity, and efficiency expected from a good health system. The collection of funds is given by a very high proportion of out-of-pocket payments, and a significant share of public resources are absorbed by the private system through the administration of statutory contributions by health insurance institutions. In terms of pooling, the blended public and private system results in a segmentation of the population among the rich and healthy versus the poor and sick.

The model is in urgent need of reform. In this sense, the commission responsible for proposing changes to the health insurance institutions system has a historical opportunity to take the necessary steps in order to set right the difficulties described in this article. Additionally, the commission should lay down the grounds for moving ahead toward a health system that recognizes health as a right.

Notes

Potential conflicts of interest

All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form translated into Spanish by Medwave and declare no relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.