Clinical reviews

← vista completaPublished on January 29, 2018 | http://doi.org/10.5867/medwave.2018.01.7148

Brief interventions to promote behavioral change in primary care settings, a review of their effectiveness for smoking, alcohol and physical inactivity

Intervenciones breves para promover cambios conductuales en el ámbito de la atención primaria: revisión de su efectividad en consumo de tabaco, alcohol y sedentarismo

Abstract

The brief intervention is a therapeutic strategy suggested to address behavioral changes associated with risk factors for chronic non-communicable diseases and there is ample evidence of its effectiveness. However, this evidence is sustained by various definitions of “brief intervention”, a fact that makes the clinical application of this strategy difficult. This literature review article aimed to conduct a search for systematic reviews in the Epistemonikos database in order to identify common factors in the definition of “brief intervention” and summarize some brief intervention strategies frequently used in primary health care. It also seeks to describe their effectiveness, for three risk factors: tobacco, alcohol and physical activity, within this clinical context

Introduction

Prevention of chronic diseases and control of related risk factors, are part of the preventive and promotional approach proposed by the World Health Organization (WHO) to reduce the growing morbidity and mortality related to chronic non-transmissible diseases (WHO 2014) [1].

Risky behaviors and substance intake are a particularly important issue, because these habits originate an important part of the burden of disease measured as years of life lost due to disability or premature death [2]. For example, tobacco is the main preventable cause of global mortality and constitutes a risk factor for six of the eight causes of mortality in the world [3]. Alcohol is the risk factor that explains the greatest number of healthy life years lost and with the highest burden of disease in Chile [1] and sedentary lifestyle, is the fourth most important risk factor for death worldwide, just behind high blood pressure and smoking, and at the same level as diabetes [1]. In Chile, more than 80% of the population is considered as sedentary [4].

Unlike other risk factors, smoking, alcohol consumption and sedentary lifestyle are adjustable behaviors and lifestyles. Therefore, strategies influencing these risk factors are of great relevance within the clinical setting. There is no doubt that addressing these health problems should be a public and intersectoral policy issue. However, it is also important that health practitioners that work day to day with the population have effective tools to promote healthy lifestyles and avoid or reduce risky behaviors in the patients with whom they interact. In particular, the primary health care teams carry out activities aimed at the prevention of risk factors and the promotion of healthy lifestyles among their users.

Brief Interventions are one of many strategies studied to address risky behaviors, which have shown to be effective in this clinical context [5]. The evidence on the use of brief interventions in diverse clinical scenarios in primary health care is broad and depends on the intervention. One of the first systematic reviews on this issue identified there was no significant statistical difference in effectiveness between brief interventions and other more extensive interventions [6], which constitutes indirect evidence on effectiveness. New reviews reinforce this fact, showing that brief interventions performed by family physicians are cost-effective in a stepped care model [7] and could lead to a short-term improvement without additional therapies [8].

The objective of this article is to conduct a review of the literature based on the available evidence about the concept of brief interventions and their effectiveness in the three risk factors for chronic diseases mentioned above: tobacco, alcohol and physical activity. All this in the clinical context of primary health care.

Evidence search methodology

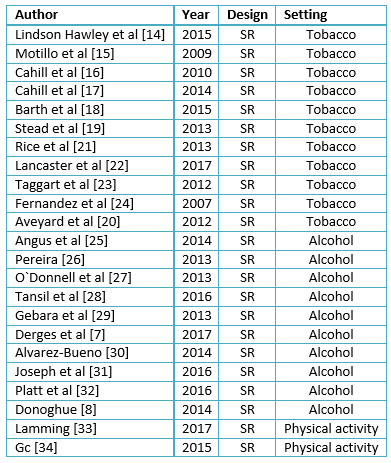

For tracking evidence on brief interventions in primary health care for tobacco, alcohol and physical activity, we performed a search of systematic reviews on "Epistemonikos" database, currently the largest database of systematic health reviews that is maintained through searches on multiple sources of information, including MEDLINE, EMBASE, and Cochrane among others. For each risk factor for chronic diseases (tobacco, alcohol and physical activity), the following search terms were used: "brief intervention *" OR "counseling" OR "brief counseling" OR "motivational interviewing". We found 299 published articles corresponding to systematic reviews and meta-analyses. We considered only studies measuring behavioral changes published during the period 2008-2017 and including brief interventions in primary health care for adult population. At least two researchers evaluated the potentially eligible reviews according to their relevance, selecting 23 in total, 11 for tobacco, 10 for alcohol and two for physical activity (Table 1). We analyzed the contents of the reviews concerning population, intervention, comparison and outcomes.

Brief intervention definition

Martha Sánchez-Craig et al. proposed the concept of brief Interventions for the first time in 1972, in Canada, and she referred to psychotherapy that sought to motivate alcohol users to modify their consumption habits in the short term [9]. However, nowadays the term is more generically used for a group of strategies from different theoretical approaches, aiming at behavioral change in the short term [5].

Then, there is more than one definition of brief intervention. The ones described in the literature differ in time duration, which fluctuates between 5 and 20 minutes per session; in the number of sessions, ranging from one to four; and on the behavioral approach defining the content and modality of the intervention. As a way of to simplify the definition concept, it could be described as a "guided conversation" with an individual about a health problem, which meets certain characteristics [10]:

- It is brief

- It has a theoretical model of reference

- It is structured

- It employs a non-judgmental communicational style

- It seeks to motivate and support the individual to plan a change of behavior

We must note that brief Interventions are more suitable for preventing purposes. In fact, it seeks a change on behavior in relation to a habit on people with a certain risk-level, unlike brief therapy, which aims to treat patients with a clinically detectable problem [10].

In recent years, efforts have been made to expand the scope of this type of intervention to reach a population that does not regularly visit primary health care, such as adolescents and young drinkers, who usually do not have chronic health problems that lead them to visit professionals. For all of this, brief interventions have also been studied in different community scenarios such as schools and universities, as well as in emergency services and hospital medicine, obtaining mixed results and inconclusive evidence regarding their effectiveness [11].

In the same way, this need to expand the scope of brief interventions has led to the development of technologies that incorporate this strategy with electronic devices for daily use; transcending the classic format of the face-to-face interview [12]. However, brief interventions have been traditionally studied and considered as strategies of the primary health care [13].

Full size

Full size Strategies for brief interventions in primary care

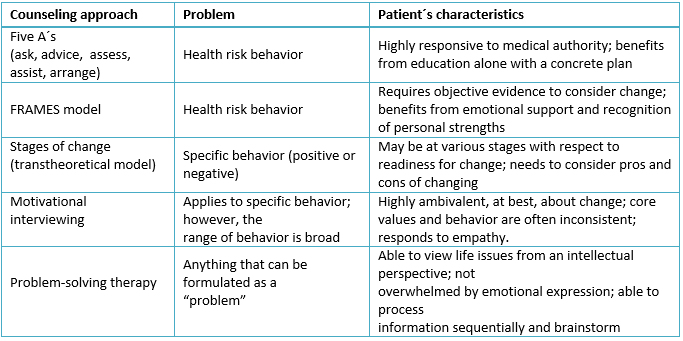

There are several brief intervention strategies applicable to primary health care, depending on the problem addressed and the characteristics of the patient. Table 2 summarizes and compares these aspects according to the approach.

Full size

Full size One of the most studied brief intervention strategies is the motivational interview, where the evidence suggests a moderate comparative advantage. It can also be used in a wide range of clinical scenarios in primary health care [13],[14].

Effectiveness in primary care

Tobacco

Among the most studied clinical scenarios is the role of brief interventions for smoking cessation. Evidence in this area shows that, specifically, the motivational interview and the "five A" model can help people quit smoking [14].

Brief intervention has shown, to induce smoking cessation on its own[15], compared to non-intervention [16],[17], with an effect that remains 6, 12 and 24 months later, making it an effective strategy with a significant clinical impact [18]. Brief interventions would increase between 1% and 3% the smoking cessation rate compared with no intervention [19]. This effect is greater when performing the intervention and offering support to all smoking patients compared to performing it only on patients who show interest on quitting smoking [20]. It has demonstrated effectiveness even beyond the medical team, when nurses [24] psychologists and health educators [21] perform the counseling to patients. The duration of a brief intervention varies between studies depending on the definition used, but evidence shows its effectiveness increases in sessions lasting about three to more than ten minutes [23].

The cessation of smoking is especially relevant for patients with coronary heart disease, where there is evidence that brief interventions are beneficial for modifying risk factors and, consequently, for the progression of coronary disease [24].

Alcohol

Regarding alcohol consumption, brief interventions have proven to be cost-effective for health systems [25], being their main objective the reduction of consumption in at-risk drinkers. Although, there is no consistent definition for problematic alcohol consumption when comparing international guidelines, there is a consensus that behavioral intervention would be appropriate for people with chronic drinking, risky drinking, and episodes of heavy drinking consumption ("binge drinking") [26],[27], [28], in both men and women [29].

The implementation of screening strategies and brief interventions in primary health care in relation to alcohol consumption presents a challenge for health professionals. Studies show that the barrier for the implementation of these strategies is the lack of perception of self-efficacy in health staff, who see this task as an overload, associated with the fact that the health system does not facilitate the ability for follow-up in case of requiring more interventions [11]. It has been seen in randomized controlled studies that a brief intervention is effective at reducing alcohol consumption on risky drinkers, both in men and women, especially when sessions last 5 to 15 minutes, with a greater effect when associated with follow-up sessions (OR=1.55, 95% CI: 1.27 to 1.90, in reduction of at-risk drinkers). When measuring the effect in grams of alcohol consumed, an average decrease of 38 g of ethanol per week is observed (95% CI: 23 to 54 g) [30]. It should be noted that a similar, or even greater, effect is observed, when non-medical professionals perform the brief intervention [27],[31], independent of the setting in which it is performed [32].

Currently, other methods of providing counseling using electronic devices are under development (e.g. computer or some mobile device); the electronic screening and brief intervention (e-SBI) method seek to identify at-risk patients and offer counseling ranging from general recommendations to reduce alcohol consumption to personalized ones. This method has shown a reduction on consumption of alcohol consumption in patients with problematic use [12] both for alcohol consumed (23.9%) and in the frequency of episodes (16.5%). The effect is maintained at 12 months of follow-up [28].

Physical activity

Although the studies are heterogeneous in their methodology, a recent systematic review shows that brief interventions alone could increase self-reported physical activity in patients, in the short term (4 to 12 weeks). However, there is not enough evidence for its long-term effectiveness, its impact on objectively measured physical activity and factors influencing its effectiveness, viability and acceptability [33]. In addition, although there is great variability among the primary studies, brief interventions seem to be cost-effective [34].

Discussion

Literature shows positive results from the use of brief interventions in smokers, with an effect maintained in the long term, regardless of their interest in quitting smoking. Using brief interventions on at-risk drinkers produce positive results, reducing alcohol consumption on both men and women by facilitating monitoring. Regarding physical activity, there is a lack of evidence to recommend a brief intervention as an objective and long-term strategy, and more studies are required to conclude on its cost-effectiveness given the great heterogeneity of the primary studies included in the systematic review.

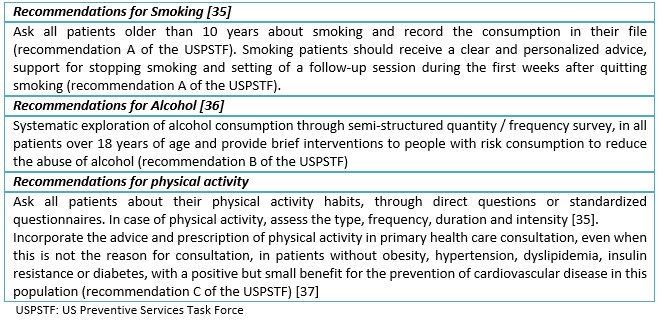

Given previous results, it seems advisable for the health teams to try to structure their brief interventions. We present, in Table 3, the recommendations suggested by the US Preventive Services Task Force, an independent panel of experts in primary care and prevention that systematically reviews the evidence of effectiveness and develops recommendations for preventive clinical services [35],[36],[37].

Full size

Full size Conclusions

The brief intervention is an effective preventive strategy to generate changes on risk factors for chronic non-communicable diseases. Although its definition is diverse, most of the studies propose it as a structured approach of no more than 20 minutes that attempts to motivate and support people in their behavioral change.

The evidence of its impact in an outpatient setting of primary health care for the approach to smoking and risky alcohol consumption is favorable, and although its results to promote physical activity are promising, more studies are required to assess its objective and long-term effectiveness.

It seems advisable for health teams to actively seek for these risk factors and try to structure their brief interventions in one of the strategies mentioned previously.

Notes

From the editor

The authors originally submitted this article in Spanish and subsequently translated it into English. The Journal has not copyedited this version.

Declaration of conflicts of interest

The authors have completed the ICMJE Conflict of Interest declaration form, and declare that they have not received funding for the report; have no financial relationships with organizations that might have an interest in the published article in the last three years; and have no other relationships or activities that could influence the published article. Forms can be requested by contacting the author responsible or the editorial management of the Journal.

Financing

The authors state that there were no external sources of funding.