Review article

← vista completaPublished on August 27, 2024 | http://doi.org/10.5867/medwave.2024.07.2931

Health conditions of migrant children and adolescents from Latin America and Caribe: A narrative review

Salud de niños, niñas y adolescentes migrantes de América Latina y El Caribe: revisión narrativa de literatura

Abstract

The presence of children and adolescents in migratory flows is growing in Latin America and the Caribbean. Little is known about migration's effects on these groups' health. This article aims to investigate the evidence available on the access and use of healthcare services by migrant children and adolescents in Latin America and the Caribbean. We seek to explore the role of social determinants of health at different levels in the health conditions of these groups. Also, to identify potential recommendations for healthcare systems and public policy to address them. For this purpose, a narrative review of 52 publications was carried out based on a search of scientific literature in the Web of Science and Google Scholar databases. Five relevant topics were identified: use of emergency care associated with lack of healthcare access, preventive services, and other social determinants of health; exposure to preventable infectious diseases; mental health; sexual and reproductive health; and vaccinations and dental health. We conclude that the evidence shows the need to address the inequities and disadvantages faced by migrant children from a perspective of social determinants of health and policies that consider health as a human right regardless of the migratory status of children and adolescents, as well as that of their parents or primary caregivers.

Main messages

- The migration of children and adolescents through Latin America and the Caribbean has increased substantially.

- Research on the impact of migratory conditions on the health of these groups is scarce.

- Healthcare teams and decision-makers need evidence to prioritize this population, recognizing their structural vulnerability and multiple inequities.

Introduction

International migration is a growing global phenomenon, defined as the movement of people out of their country with the intention of settling. This definition does not usually consider the reality of children and adolescents whose presence in migratory flows has increased. The United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) [1] estimates that there are 244 million migrants worldwide, of whom 31 million are under 18 years of age and 6.3 million are in the Americas. The recent crises in Haiti and Venezuela, together with the closing of borders due to the COVID-19 pandemic, have increased the flows and made the conditions of migrants more precarious [2].

Migration is a recognized social determinant of health, whose conditions impact the health outcomes of those who migrate [3,4]. Social determinants influence the development and well-being of people throughout their lives [5], with childhood and adolescence being key groups. This is because the first years of development play a fundamental role in the generation and maintenance of social and health inequities reproduced and perpetuated in adult life [4]. Although some countries in our region have made socioeconomic progress, serious inequities persist concerning determinants affecting children and adolescents. These determinants include access to healthcare, education, water and sanitation, adequate nutrition, and exposure to violence, among others [6]. For those who migrate through Latin America, these inequalities are exacerbated by the conditions in which they often transit through and enter the country of arrival, often leaving them in an irregular situation [7].

Considering the increase in the number of children and adolescents in human mobility flows through the continent, this article aims to investigate the evidence available on the access and use of healthcare services by these groups in Latin America and the Caribbean. In this way, it seeks to reflect on the role played by social determinants of health at different levels and identify recommendations for their approach from the healthcare and public policy systems.

Methods

We conducted a narrative literature review [8], applying the rigorous search guidelines of a systematic review. In total, three literature searches were performed. In the first instance, a search was carried out in the Web of Science database (December 2022) with the following search equation:

("Health Services"[MeSH] OR "health care" OR "Health service access" OR "Health service acceptability" OR "Health care access" OR "Healthcare access" OR "Health care acceptability" OR "Healthcare acceptability" OR "Specialised health services" OR "Specialist" OR "Hospitalisation" OR "Emergency health services" OR "Mental health services" OR "Preventive health services" OR "health check-ups" OR "primary service" OR "dental care" OR "dental") AND ("Transients and Migrants"[MeSH] OR "Emigrants and immigrants"[MeSH] OR "Refugee" OR "Migration background" OR "Immigrant background" OR "Migrant" OR "Immigrant" OR "irregular migrant" OR "undocumented migrant" OR "Ethnic minority") AND ("Child"[MeSH] OR "Children" OR "Adolescent" OR "Adolescents" OR "Youth" OR "minor") AND ("culture" OR "cultural" OR "culturally competent care" OR "cross-cultural care").

The search was filtered by date (from 2012 to 2022) and language (English, Spanish, French, Portuguese). This search in Web of Science yielded 544 results.

Secondly, to include relevant Latin American scientific literature that might be absent in the Web of Science databases, a second search was conducted in Google Scholar in Spanish (December 2022) with the following equation and ten-year filter (from 2012 to 2022):

(servicios de salud) AND (acceso OR aceptabilidad) AND (barreras OR facilitadores) AND (niños OR niñas) AND (adolescentes OR jóvenes) AND (migrantes OR refugiados) AND (salud intercultural).

Here 15 300 results were found. Because of this, we decided to consider the first 400 titles because, after that amount, the results began to become repetitive or irrelevant to the search. Eighteen duplicates were eliminated. At this point, the first review was performed based on titles and abstracts of the 544 results from Web of Science, added to the 400 results from Google Scholar, eliminating 18 duplicate results (n = 926). The following exclusion criteria were then applied (Table 1):

This initial review process led to the exclusion of 810 publications. A total of 116 full texts were reviewed, 25 from the Google Scholar search and 91 from the Web of Science search. Five articles were discarded based on the following exclusion criteria (Table 2), leaving 111 articles selected after the full-text analysis:

After analyzing the 111 selected texts, it became clear that the articles older than five years contained outdated information due to the important changes Latin American migration has undergone in recent years. For this reason, and to update the search, a filter was applied that eliminated studies older than 2017 (n = 68). As a result, 43 articles were selected for inclusion in the review from 2017 to 2022.

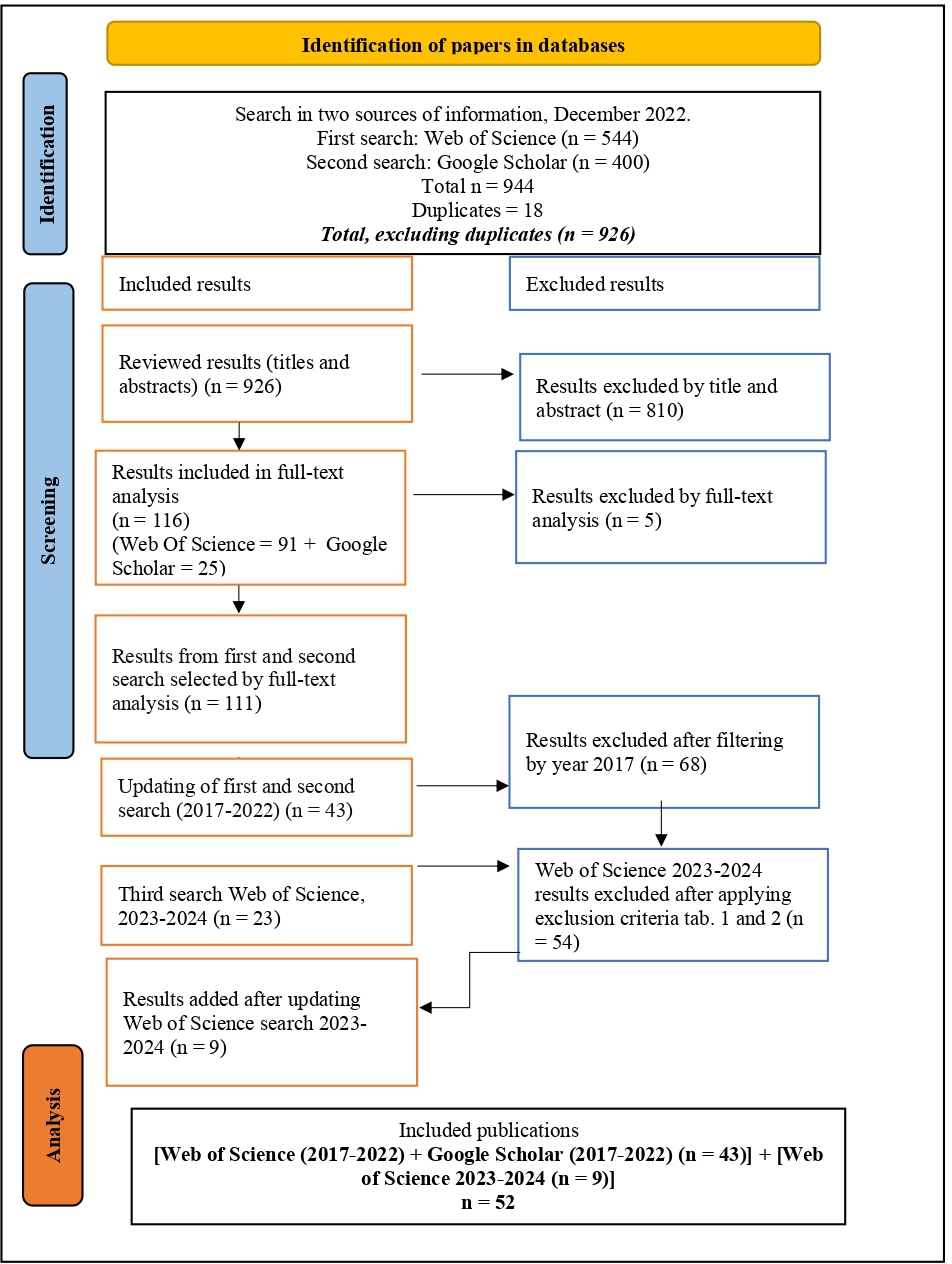

Finally, to maximize the relevance of the research, on January 15, 2024, a third search was carried out using the same systematic applied to the Web of Science database, this time using the year filter from 2023 to 2024. A total of 63 articles were found, whose titles and abstracts were analyzed using the same criteria as above (tables 1 and 2). From this process, nine articles were selected and manually added to the previous sample of 43. In conclusion, 52 articles were analyzed. The PRISMA flowchart summarizes the selection process based on the Preferred Reported Items in systematic reviews and meta-analyses [9] (Figure 1).

PRISMA flow chart of the included studies in the narrative literature review.

Results overview

Regarding the origin of the studies, the articles come from countries such as Chile (n = 7), Argentina (n = 3), Colombia (n = 8), Peru (n = 2), Mexico (n = 3), Nicaragua (n = 1), Dominican Republic (n = 1), United States (n = 10), Canada (n = 8), and the Americas (global approach), which include analyses for Latino or Hispanic children and adolescents (n = 9).

The thematic analysis of the studies allowed us to identify five themes in which there is relevant evidence regarding access and use of healthcare services by migrant children and adolescents:

-

Use of emergency care due to lack of access to healthcare.

-

Exposure to infectious diseases due to causes attributable to social determinants.

-

Social vulnerability, mental health, and exposure to violence.

-

Sexual and reproductive health.

-

Inequities in access to vaccinations and dental health.

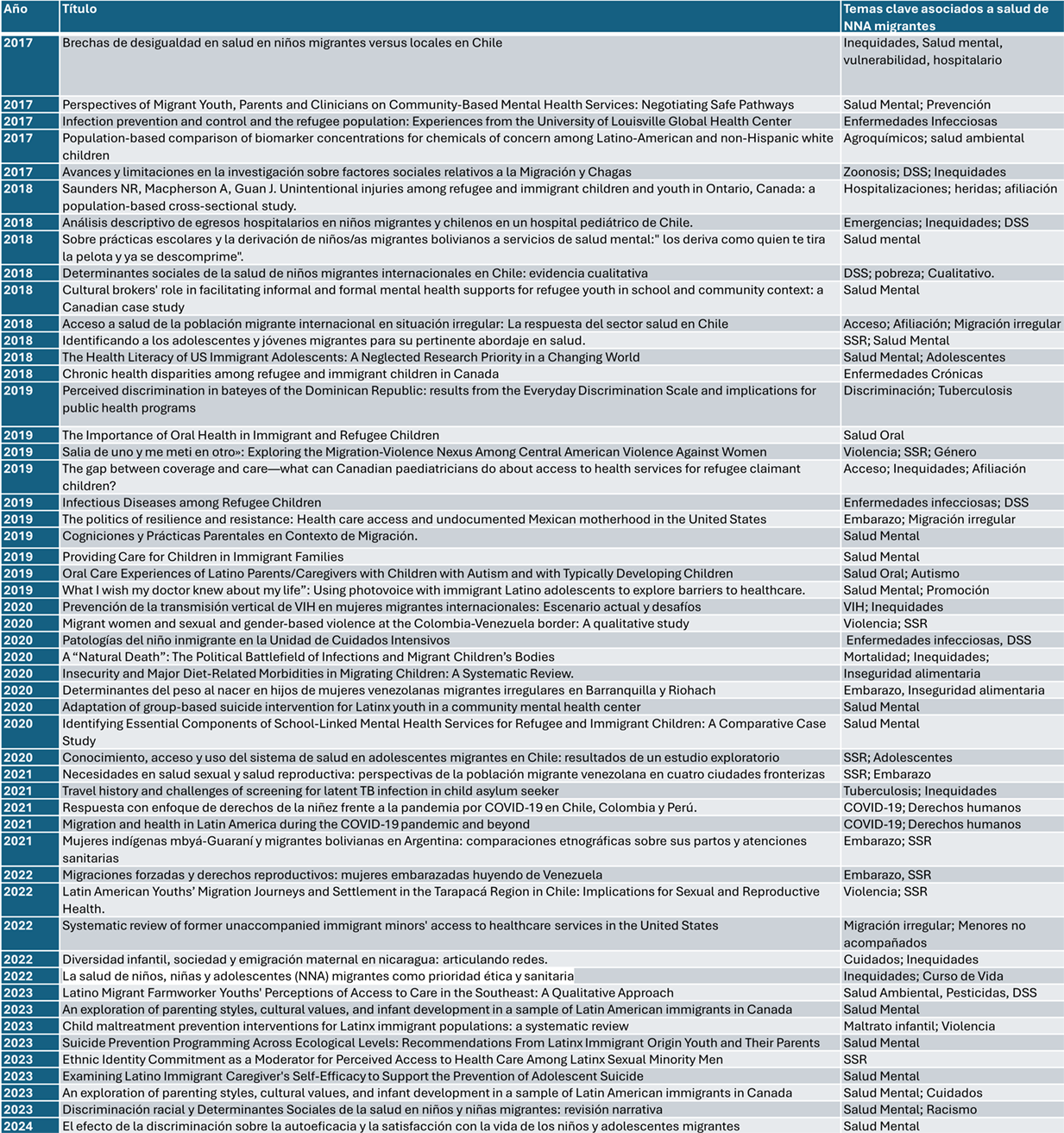

Figure 2 shows a summary table of the references considered for the analysis.

Summary table of the references.

Use of emergency care due to lack of access to healthcare

One of the areas where inequality between migrant and local children and adolescents is evident can be seen at the level of emergency hospital admission records. These records contain information on morbidity and health coverage of those who attend these centers. Research carried out in Chile [10,11] shows that migrants between 7 and 14 years of age are more frequently admitted to hospitals for trauma and other external causes than Chileans [10]. Another analysis from the same country [11] confirms that migrant children are more likely to suffer infectious diseases requiring hospitalization, as well as morbidities associated with accidents such as burns or fractures. All these events are linked to social determinants of health, such as housing conditions, access to drinking water, overcrowding, environmental conditions, exposure to pollutants, and low temperatures [12]. In both analyses, when comparing the health coverage presented by users at the time of care, difficulties in access to primary care services by migrant children are evident [10,11,13]. Data from Canada show that migrant children without health insurance were overrepresented in emergency triage [14]. In the United States, a study investigated reported barriers to access to outpatient services. Many of them are linked to cultural differences in healthcare, lack of language skills, lack of knowledge of available healthcare resources, and the need to prioritize work over self-care [15].

Exposure to infectious diseases due to causes attributable to social determinants

Another area of concern [16,17,18,19,20,21] is the exposure of migrant and refugee children and adolescents to diseases such as tuberculosis, hepatitis B and C, dengue, malaria, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and Chagas disease. The critical conditions of deportation and detention of Latino children at the U.S. border have been associated with deaths due to septicemia [18]. The case of tuberculosis has been studied, given its prevalence in low-income countries [19], the origin of many of the migrations of children and adolescents through the continent. The development of the disease is aggravated if it is associated with factors present in many migrant children, such as malnutrition, stress, and overcrowding [20]. Regarding malaria, a study [21] conducted in the Dominican Republic with Haitian migrants found that perceived stigmatization and discrimination are frequent among people of Haitian origin. They often identify it as a barrier to seeking healthcare and participating in community programs. Finally, in the case of HIV transmission, this is framed in the complex interaction between migration, gender, and sexual health. In Chile, an analysis [22] showed an increase in the number of foreigners living with HIV, with a particular concern for women of Latin American origin. They often come from contexts of structural vulnerability. In addition, they may have been exposed to sexual abuse and violence at origin, transit, or arrival, as has been observed in the displacement of Latin American women to the United States [22,23] and of young Venezuelan women through the Southern Cone [24]. Pregnancies that may result from these aggressions are subject not only to difficulties in reporting [24] but also to less access to pregnancy control, with consequences on the possibility of accessing early diagnosis and antiretroviral treatment, if required by the mother and/or child [22,25].

Social vulnerability, mental health, and exposure to violence

The healthcare crisis caused by COVID-19 increased the vulnerability of migrating children and adolescents [6,26]. These include not only the critical conditions in which displacement across irregular borders has taken place [27] but also the reproduction of inequalities faced by migrant children. This group was excluded from distance education programs and exposed to risk situations at home and abroad linked to the informal work of parents and caregivers [6].

Specific issues related to social vulnerability experienced by migrant children and adolescents include food insecurity, early caries, deficient or excess nutritional problems [28,29], and exposure to pesticides [30]. Some of these vulnerabilities are accentuated in girls and pregnant women [29]. In the United States, some studies reveal the presence of stressors related to the migratory history of Latino families and their living conditions in the destination country [31]. The effects that these conditions generate on the mental health of these groups are also evidenced by the literature. Socioemotional needs related to unfamiliarity with the local territory, experiences of discrimination, language barriers, and emotional effects related to being away from their loved ones are reported [32,33]. Difficulties related to not sharing or not knowing the migration project chosen by the adults are also highlighted, in addition to the stress to which parental relationships are subjected in a migratory context [34,35]. It is also important to note that the literature also identifies the resilience capacity demonstrated by migrant children [36,37]. This capacity is strengthened by inclusive social environments that promote the recognition of their multiple belongings.

Sexual and reproductive health

The healthcare needs of the adolescent migrant population are often overlooked by policies focused exclusively on adulthood or early childhood. Regarding reproductive health, studies [38,39] report a higher proportion of immigrant mothers with biopsychosocial risk, with less screening and pregnancy controls [9]. Regarding sexual health, studies conducted with adolescent migrants emphasize the need for condom access and information on how the health system works in the country of arrival [24,38]. In Latin America, adolescent pregnancy continues to be present in a significant proportion of countries of origin of south-south migration. Some studies suggest that it may particularly affect adolescent migrants [38,40]. A study in Argentina highlights the presence of adolescent pregnancies in young Bolivian women in family contexts that normalize this situation and in couples formed at an early age [40]. It also highlights the anticipated assumption of responsibilities that young people experience in terms of work and caring for others. Added to this is the distance they establish with the countries of arrival healthcare systems, either due to lack of knowledge or accessibility [41].

Inequities in access to vaccinations and dental health

Finally, essential aspects in the field of prevention appear as dimensions in which migrant children and adolescents are at a disadvantage concerning their local peers. Studies from the United States [42,43] estimate that children of Latino origin in that country have the highest prevalence of caries [42], linked to factors such as diet, lack of prioritization and access to dental care services, lack of access to healthy foods, and the use of cariogenic foods in transit and settlement processes as a response to hunger. Regarding vaccination in the United States, most of the refugee children seen in one primary healthcare center have not received the primary vaccination schedule for preventable diseases of low incidence or eradication in the country [43]. This could be repeating itself in migrant children throughout the Latin American and Caribbean region, given the inequities in vaccination that have been detected at the global level.

Discussion

Migrant children and adolescents represent a growing population in the region. Therefore, guaranteeing the right to health implies a fundamental commitment of the States of the continent, not only because of the moral duty to ensure the integral well-being of children but also because of the long-term impact that the accumulation of socio-health vulnerabilities from this stage of life can have on the population [4,5,44]. This literature review presents relevant issues in which it is possible to observe the effect of social determinants on the generation of inequities that impact this population’s current and future health outcomes. First, regarding the use of emergency services due to healthcare access barriers that affect the irregular migrant population in particular [14,45], it is essential to strengthen regional mechanisms that guarantee healthcare coverage and access to prevention and health promotion services for migrant children and adolescents. This should be done regardless of their and/or their parents' migratory status, aiming to reduce the use of emergency services, avoid hospitalizations [46], and increase the coverage of preventive programs. Intersectoral actions coordinated with the education sector are key to reducing enrollment gaps. However, as the literature [3] indicates, access to healthcare services is insufficient unless it is accompanied by policies addressing social determinants such as housing conditions, access to drinking water, education, and care systems. Unfortunately, these rights are not yet within the reach of all children and adolescents on the continent [4].

Secondly, the infectious disease situation reflects the challenges still pending in the area of global health, which have been accentuated since the COVID-19 pandemic. On the one hand, regarding tuberculosis, Latin America is one of the areas with increased incidence [47], requiring the generation of regional strategies that go beyond national borders and allow the coordination of clinical, socioeconomic, and public health actions [47]. These should involve the participation of communities, civil society organizations, and healthcare providers, whose common objective should be to strengthen the social protection of particularly vulnerable groups such as migrant children and achieve universal health coverage. The HIV data also point to the need for specific actions in the area of sexual and reproductive health focused on the migratory population [48]. Here, it is important to recognize, as has been done since the International Conference on Population and Development (Cairo, 1994), that migrants and displaced persons have limited access to sexual and reproductive healthcare, which may expose them to serious health and reproductive risks. This is particularly important if we consider that the risks of suffering gender-based violence and/or being victims of human trafficking and smuggling disproportionately affect girls and adolescents who are in forced relocation and migration [7]. Actions on infectious diseases that may affect migrant children and adolescents should consider the stigmas suffered by this type of pathologies, as well as the risks of revictimization that imply interventions without participatory and inclusive approaches from civil society and the migrant community.

Third, in terms of mental health, the findings are conclusive regarding the impact that the conditions of relocation and insertion in the country of arrival have on the socio-emotional well-being of migrant children and adolescents. Exposure to various types of violence, food insecurity, risks associated with organized crime, child labor, and periods of living on the street impair their possibilities for emotional and cognitive development. This generates difficulties in performing daily activities and affects their identity construction [33]. The lack of cultural relevance of mental health programs for children and adolescents and the difficulties experienced by parents and caregivers in the performance of their parenting tasks due to economic and labor precariousness accentuate these difficulties [34,35]. All this highlights the urgency of developing intersectoral actions that, on the one hand, reinforce protective factors in children, adolescents, and parents [34] and, on the other hand, allow the detection and treatment of symptoms through the mental health care systems in the countries of arrival.

Fourth, regarding sexual and reproductive health, the findings identify the need to generate intersectoral actions to bring healthcare promotion and prevention services closer to groups that are facing inequities, such as adolescent migrants. Lack of knowledge of healthcare programs, the need to prioritize work and studies over self-care, and the fear of being discriminated against in care are barriers reported in adolescents through various studies [39,41]. These studies agree on the need to generate specific measures to increase the accessibility and cultural relevance of programs dedicated to this population.

Finally, inequities in vaccination and dental health issues challenge both research and the implementation of preventive programs. The analyzed results indicate the need for more evidence on the effects of food insecurity and transition on oral and nutritional health care [42]. The same applies to the availability of vaccines and the continuity of immunization programs in the countries where children and adolescents migrate [43]. Future research could address these issues, including the global health approach to implementing immunization programs.

Conclusions

This review provides evidence on the situation of access and use of healthcare services by migrant children and adolescents in Latin America and the Caribbean. This allows us to reflect on the role of social determinants at different levels in the health conditions of these groups.

The identification of five topics on which there is consistent evidence regarding the inequities that are affecting this age group makes it possible to generate recommendations for actions at different levels that governments, healthcare systems, and institutions in the region can take.

Guaranteeing universal access to healthcare regardless of the migratory status of children and adolescents and/or their parents or caregivers is one of several commitments to be made in order to ensure that healthcare is a right exercised by all children. Of course, it also includes those who are migrating.