Estudio cualitativo

← vista completaPublicado el 9 de octubre de 2024 | http://doi.org/10.5867/medwave.2024.09.2963

Actividad física en chilenas sobrevivientes de cáncer de mama: estudio cualitativo de barreras, facilitadores y preferencias

Physical exercise in Chilean breast cancer survivors: Qualitative study of barriers, facilitators and preferences

Abstract

Introduction Breast cancer survivors often experience pre and post-treatment physical and psychological symptoms, negatively affecting their quality of life. Regular physical exercise is associated with better quality of life and lower recurrence of cancer, and therefore all oncological patients are recommended to practice it in a regular basis. Despite this, breast cancer survivors have low adherence to physical exercise. The purpose of this study is to identify barriers, facilitators and preferences of Chilean breast cancer survivors to practice physical exercise.

Methods Phenomenological qualitative study of 12 in-depth interviews with adjuvant radiation therapy concluded at least three months ago.

Results Breast cancer survivors ignored the benefits of physical exercise during and after treatment. The barriers were physical symptoms, psychological barriers, sociocultural barriers, health system barriers, disinformation and sedentary lifestyle. Facilitators were coping with physical symoptoms, psychological issues, having information and active lifestyle. The preferences were painless and familiar exercises. Preferred exercise was walking.

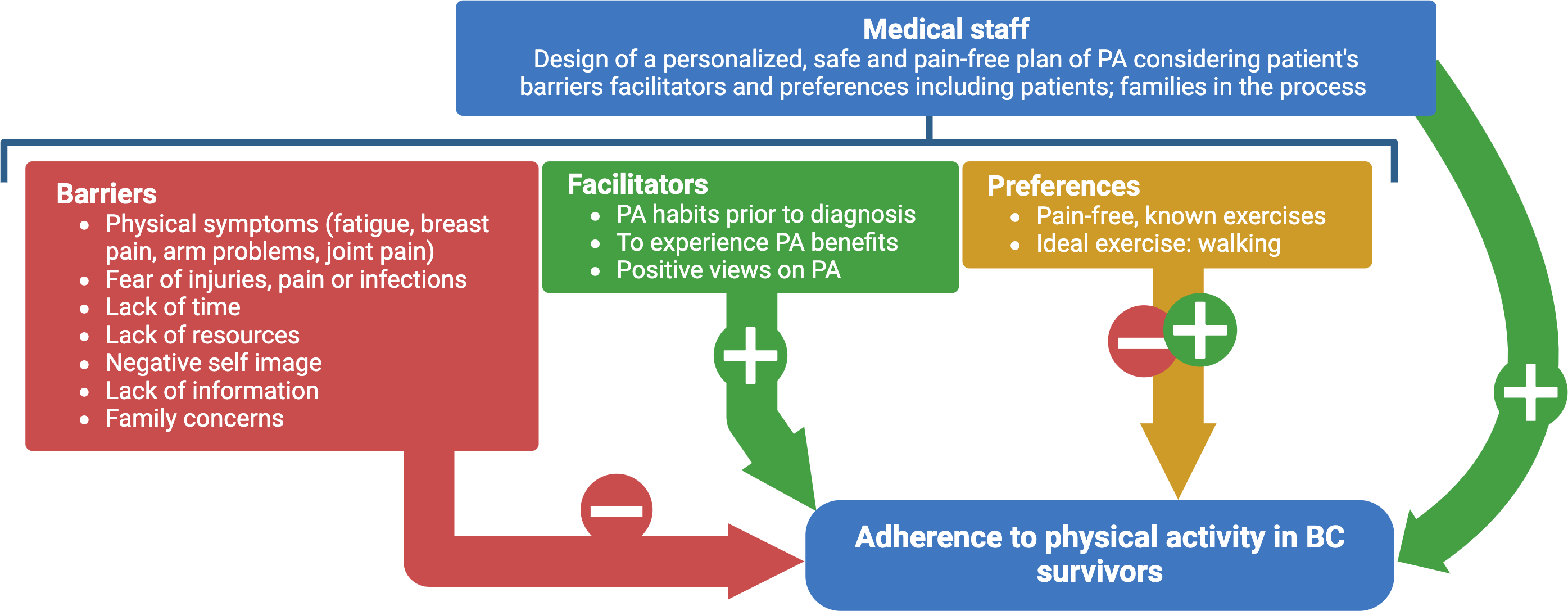

Conclusions Breast cancer survivors may adhere to physical exercise despite barriers when certain facilitators are present, which may be promoted by the health team when reporting the benefits of the physical exercise, prescribing personalized, safe and painless physical exercise and educating both patient and her family about the role of the physical exercise in cancer recovering process.

Main messages

- This study reveals a low adherence to physical exercise among breast cancer survivors.

- Studies identifying the reasons for this low adherence are so far lacking.

- Although the sample size is limited, the main finding highlights the urgent need for a comprehensive healthcare team approach to address these barriers and promote adherence to physical exercise.

Introduction

Breast cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related death in women and the most commonly diagnosed cancer in Chile and the world [1]. Its incidence ranged between 27.7 and 37.7 per 100 000 Chilean women in 2020 [1,2]. In Chile in 2015, the five-year survival rate was 80.6% [3]. A patient is considered a breast cancer survivor from the time of diagnosis until death, a period that is becoming increasingly longer due to early diagnosis and better medical treatment [4,5,6]. Breast cancer survivors experience symptoms such as pain, fatigue, low mood, and anxiety during and after treatment, diminishing their quality of life in the medium and long term [3,7].

In Chile, breast cancer is included in the Explicit Health Guarantees system, which guarantees screening, diagnosis, surgical treatment, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, follow-up, rehabilitation, pain relief, and palliative care. One of the objectives of the follow-up is to manage the treatment’s side effects and promote a healthy lifestyle that includes physical activity. Physical exercise is ‘any planned, structured and repetitive physical activity to improve physical fitness’. Several studies show that physical exercise decreases breast cancer recurrence and physical and psychological symptoms during and after treatment and allows early return to work for breast cancer survivors [3,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14].

For this reason, breast cancer management guidelines, such as the National Cancer Plan of the Chilean Ministry of Public Health from 2018 to 2028, the Clinical Guide of the Explicit Health Guarantees System for breast cancer and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Cancer Survivor Care Guidelines advise regular physical activity [1,9,11,12,13]. Cancer patients are recommended to engage in 150 minutes or more per week of moderate aerobic physical activity or 75 minutes or more per week of vigorous aerobic physical activity [12,13]. Moderate physical activity equates to a task metabolic rate of three to six, such as brisk walking or housework, and vigorous physical activity parallels a task metabolic rate equal to or greater than 6, such as jogging [7,12].

However, due to barriers such as physical symptoms, misinformation, and lack of time, adherence to physical activity is low among breast cancer survivors [3,15,16]. Although in Chile there are programs to promote healthy eating and physical exercise for the general population, it is a pending task to design benefits aimed mainly at women breast cancer survivors to promote physical exercise.

There is evidence that sedentary breast cancer survivors adhere to physical exercise programs during and after treatment when guided and supported by the medical team [17,18]. We aim to identify barriers, facilitators, and preferences of Chilean breast cancer survivors concerning physical exercise in order to increase their adherence.

Methods

The reporting guideline for qualitative research available on the Equator Network was used. The qualitative study was based on semi-structured, in-depth interviews. We used convenience sampling, as a group of women breast cancer survivors were already participating in a study by the same research team. Participants were selected from the National Fund for Scientific and Technological Development project, FONDECYT, 11190071 ‘Multimodal evaluation of acute cardiac toxicity induced by thoracic radiotherapy’. The inclusion criteria were:

-

Female sex.

-

Non-metastatic breast cancer.

-

Over 40 years of age.

-

Having completed adjuvant radiotherapy at least three months previously.

All participants were being treated at the Cancer Centre of the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile.

Twelve breast cancer survivors were interviewed, with a median age of 51 years (40 to 75 years), seven lived in Santiago and five in other regions. Regarding the type of surgery, nine of them underwent a partial mastectomy, and three underwent a total mastectomy. At the time of diagnosis, two were stage 0, two were stage I, four were stage II, and four were stage III. None of them were stage IV.

Patients who had survived breast cancer were invited by telephone to participate in the study. After signing informed consent, they were interviewed remotely by telephone or Zoom® platform for an average of 36 minutes, ranging from 23 to 79 minutes. Interviews were audio-recorded, with patients' permission, and then transcribed verbatim. A script of open-ended questions was used. During the interview, new topics were added as deemed relevant based on information provided by the study participants.

Data analysis was carried out using Atlas.ti ® software (version 9.1) by the psychologist who conducted the interviews. This professional has experience in qualitative analysis, following the methodological principles of interpretative phenomenological analysis, which, through textual discourse analysis, seeks to understand the meaning of human phenomena [19].

The interviews were analyzed as they were conducted in order to adjust the script to the emerging themes. The interviews were stopped once the coding categories were saturated, i.e., when the analysis yielded no new concepts. In order to achieve a high methodological quality, the categories were triangulated with the research team, and each category was substantiated with phrases extracted verbatim. In addition, an inductively completed analysis matrix was drawn up [20]. The transferability of the findings was achieved by presenting the socio-demographic characteristics of the participants in this study (Table 1).

The protocol was approved by the Scientific Ethical Committee of the Faculty of Medicine of the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile (ID 190318006). The study was conducted between December 2020 and January 2021 during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Results

The characteristics of the sample are presented in Table 1.

There were two groups of patients concerning physical exercise: one was physically active before, during, and after treatment, and the other was always sedentary. The active group consisted of two women who survived breast cancer. One did one hour of jogging, strength, flexibility, and relaxation exercises; the other rode a mobile bicycle for 40 minutes daily.

Both groups reported similar barriers, but those in the sedentary group perceived them as insurmountable. In contrast, the physically active exercised despite the barriers, which were classified into five groups (see Table 2).

Physical symptoms

The most relevant was fatigue, associated with pain, mastalgia, arthralgia, nausea, vomiting, and/or reduced upper limb mobility. Physically active patients reduced the intensity of physical exercise when experiencing symptoms.

Psychological barriers

Sedentary women feared exacerbating physical symptoms, injury and/or infections such as COVID-19. They did not mention psychiatric symptoms. Physically active women did not express these fears.

Misinformation

Sedentary patients were unaware that physical exercise improved the quality of life of women breast cancer survivors and did not know what type of physical exercise to do. On the other hand, physically active women were aware of the benefits and characteristics of the physical exercise they could practice.

Health system

All study participants reported that their medical team had not informed them about the importance of physical exercise for breast cancer survivors. They were also not clearly prescribed physical exercise in frequency, intensity, or duration. Only mobility exercises for the management of upper limb lymphoedema were prescribed.

Socio-cultural barriers

Most women reported that their families opposed physical exercise for fear of injury or fatigue. In addition, household chores and work did not leave them enough free time to exercise. At the time of the interview, four participants were homemakers, five had a jobs outside the home, and three were on medical leave. Regarding the physical environment, living in a neighborhood with no green areas or unsafe neighborhoods decreased the motivation to exercise. Some mentioned a lack of resources to afford a gym or to buy an exercise machine. Patients did not mention kinesiotherapy as a resource for physical activity.

Sedentary before breast cancer diagnosis

Women who were sedentary before breast cancer diagnosis continued to be sedentary during and after treatment. In addition, they reported that their sedentary lifestyle was a trait that could not be modified.

The facilitators identified were categorized into four groups and were reported only by physically active participants.

Physical facilitators

Physically active women reported that exercise helped them sleep better and have greater flexibility and energy during the day.

Psychological facilitators

Physically active participants reported better moods and less anxiety to face the day when they exercised.

Information

Physically active women believed it was essential to stay physically active. Therefore, they decided to make an extra effort to exercise even when they felt pain or fatigue.

The patients who were physically active during and after treatment were physically active before their breast cancer diagnosis. One is an actress, and the other uses bicycles as her main means of transport.

Regarding preferences, the female breast cancer survivors preferred familiar and painless exercises. They discarded rebounding and strength exercises such as weights, elliptical, or jogging. Walking was the ideal exercise because it was painless and low impact. There was no clear preference for group or individual exercise, at home or in a gym, with or without supervision. There were no trends according to age, occupation, decile, stage of breast cancer or treatment received.

Discussion

This study aimed to identify the main barriers, facilitators, and preferences of Chilean women breast cancer survivors to exercise, as adherence to exercise is often low.

Concerning barriers, fatigue was the most frequently mentioned symptom. It is reported that 80-96% of breast cancer survivors experience fatigue during chemotherapy and one-third months or years post-treatment [3].

Women breast cancer survivors reported physical symptoms such as breast pain, arthralgia, and upper limb pain. They reported fear of pain, injury, or infection during exercise, consistent with recent evidence [15,17,20,21].

They also reported a lack of time to exercise due to domestic and work tasks. This is consistent with international and national studies in which Chilean women breast cancer survivors with more children had greater difficulty exercising [7,16,20,21].

The families of the breast cancer survivors in our study and international studies often discourage them from exercising, believing that the treatment and recovery of a cancer patient requires physical rest [18,22].

Having a personal history of a sedentary lifestyle is, according to the literature, a barrier to physical exercise. Women breast cancer survivors who define themselves as ‘bad at exercise’ consider it an intrinsic and unmodifiable trait [23].

Some women mentioned living in an unsafe neighborhood and/or without green areas. It is important to note that two participants are at the extreme poverty line and that half of the participants in our study are below the median income, according to the Casen 2020 Survey. This is associated with the abovementioned barriers (see Table 1) [16,24,25].

While low mood and negative body image are reported in the literature as barriers, these were not mentioned by our respondents. It is likely that they are sensitive issues and were, therefore, not spontaneously reported.

According to several studies, female breast cancer survivors with the same barriers reported by our participants consistently adhere to physical exercise up to 80%, when their medical team informs them of the benefits of physical exercise and prescribes a personalized, flexible, safe and painless plan [9,17,18,15, ].

However, less than 50% of cancer patients receive information on the role of physical exercise, and most women who have survived breast cancer only receive recommendations to maintain upper limb mobility [18]. Most of our participants reported not being informed by their medical team about the benefits of physical exercise or receiving recommendations on its practice. According to a Chilean study, 95% of female breast cancer survivors are interested in receiving information about physical exercise, and 92% are interested in participating in a physical exercise program [9]. Concerning facilitators, exercising and physically and mentally experiencing its benefits increases adherence to exercise [20,21,22,22]. Participants in our study who exercised daily reported that physical exercise gave them more encouragement, energy, less pain, and fatigue and that when they stopped training - ‘the body was asking to exercise’.

Having the habit of exercising before diagnosis also facilitates exercise during and after treatment [22]. The two interviewees who exercised daily before the diagnosis of their disease maintained this routine during and after treatment.

It is relevant to analyze structural barriers to the practice of physical exercise by breast cancer survivors. Although the Ministry of Health has developed the Elige Vivir Sano campaign and the Vida Sana program to promote healthy eating and physical activity, these initiatives are aimed at the general population [12].

On the other hand, breast cancer is a pathology of the Explicit Health Guarantees system that ensures the follow-up of breast cancer survivors, the management of the side effects of cancer treatment, and the promotion of a healthy lifestyle. Unfortunately, in our country, there are still no strategies specifically designed for breast cancer survivors to promote regular physical exercise [11,12].

Regarding preferences, our participants preferred painless and familiar exercises. As in other studies, they considered walking the ideal exercise because it is painless and has little joint impact [23]. Walking is a prescriptive exercise for breast cancer survivors of different ages and disease status. Moreover, it does not require financial resources, although living in an unsafe neighborhood could be a limitation [3].

According to the literature, breast cancer survivors prefer to attend physical exercise programs with other women in the same condition and to be supervised by a professional with knowledge about exercise and cancer [23,26,27,28]. In addition, they feel more comfortable sharing spaces with people with similar cosmetic sequelae and exchanging experiences about the disease [19,22,23]. A person educated in the recovery process of women breast cancer survivors knows their symptoms, empathizes with them, and adapts to exercises better [15,22,23]. According to a Chilean study, 76% of these Chilean patients would prefer to exercise with other breast cancer survivors, and 94% would choose supervised exercise [7]. However, in our research, the respondents did not express a preference for exercising with other female breast cancer survivors. This is probably because they have not had the experience of doing so and were not asked in a targeted manner.

Suggestions for increasing exercise adherence in women breast cancer survivors are presented below (see Figure 1).

Dynamics of barriers, facilitators and physical exercise preferences of Chilean breast cancer survivors.

Abbreviations: PA, physical activity. BC, breast cancer.

-

Before prescribing physical exercise, it is necessary to rule out uncontrolled comorbidities, severe cachexia, and bone metastasis, especially in patients in advanced stages of breast cancer and/or receiving chemotherapy with cardiopulmonary effects [3].

-

Start physical exercise early in treatment to encourage adherence.

-

Plan and coordinate follow-up between different health care professionals and levels of care.

-

Educate women breast cancer survivors and their families about the benefits of exercise, emphasizing that it is an essential part of cancer treatment and secondary prevention and that it can be safe and painless.

-

Prescribe a flexible and personalized physical exercise plan, directed and supervised by a qualified health professional, specifying type, frequency, duration, and intensity.

-

Offer group exercise spaces for women breast cancer survivors, either face-to-face or via remote communication platforms.

-

Develop a Guide for Cancer Survivors that promotes physical exercise and a healthy lifestyle.

Finally, regarding the limitations of our research, our sample was composed of women over 40 years of age, predominantly from middle and low socioeconomic strata, with an underrepresentation of older women. Therefore, our results are not generalizable to female breast cancer survivors younger than 40, older women, other socio-demographic groups, or men with breast cancer. At the time of diagnosis, none of our respondents were in stage IV breast cancer. For this reason, these results are not generalizable to patients with metastatic breast cancer.

Conclusions

Given the findings of this study, breast cancer survivors can adhere to physical exercise despite barriers when specific facilitators are present. The medical team can generate these facilitators by informing them about the benefits of physical exercise, prescribing personalized, safe, and painless physical exercise, and educating the patient and her family about the role of physical exercise in the recovery of breast cancer survivors.