Estudios originales

← vista completaPublicado el 5 de agosto de 2022 | http://doi.org/10.5867/medwave.2022.07.002545

Revalidación de escala ultracorta para la medición de la seguridad percibida para conservar el trabajo en Latinoamérica

Revalidation of an ultra-short scale for the measurement of perceived job security in Latin America

Abstract

Introduction Due to the measures imposed by governments to reduce the spread of this new virus, the economic sector was one of the most affected during the COVID-19 pandemic. Several labor sectors had to undergo a virtual adaptation process resulting in job instability and job loss. The objective of this study was to revalidate an ultra-short scale for measuring perceived job security in Latin America.

Methods A revalidation study was done on a short scale that measures worker’s perceived security about losing or keeping their job in the near future.

Results The four items remained on the revalidated scale, where all four explained a single factor. The goodness-of-fit measures confirmed the single-factor model (χ: 7.06; df: 2; p = 0.29; mean square error: 0.015; goodness-of-fit index: 0.998; adjusted goodness-of-fit index: 0.991; comparative fit index: 0.999; Tucker-Lewis index: 0.997; normalized fit index: 0.998; incremental fit index: 0.999; and root mean square error of approximation: 0.036). The scale’s reliability was calculated using McDonald’s omega coefficient, obtaining an overall result of ω = 0.72.

Conclusions The scale was correctly revalidated in Latin America, and the four items were kept in a single reliable factor.

Main messages

- Due to government measures to reduce contagion, the economic sector was one of the most affected during the COVID-19 pandemic. Several labor sectors had to undergo a virtual adaptation process resulting in job instability and job loss.

- In a context of informality, the pandemic hindered work through containment measures and generated the need to care for sick family members. These represent highly stressful situations that can affect the mental health of workers.

- Although there is a validated scale on the perceived job security of workers in the COVID-19 pandemic context, this validation was carried out only in the Peruvian labor setting.

- The revalidation of the WORK-LATAM-COVID-19 scale provides Latin America with an instrument to objectively assess workers' perceptions of their employment and job security.

- Selection bias is a limiting factor in this study since it has a non-random sample. In addition, the bulk of the sample corresponds to an urban population.

Introduction

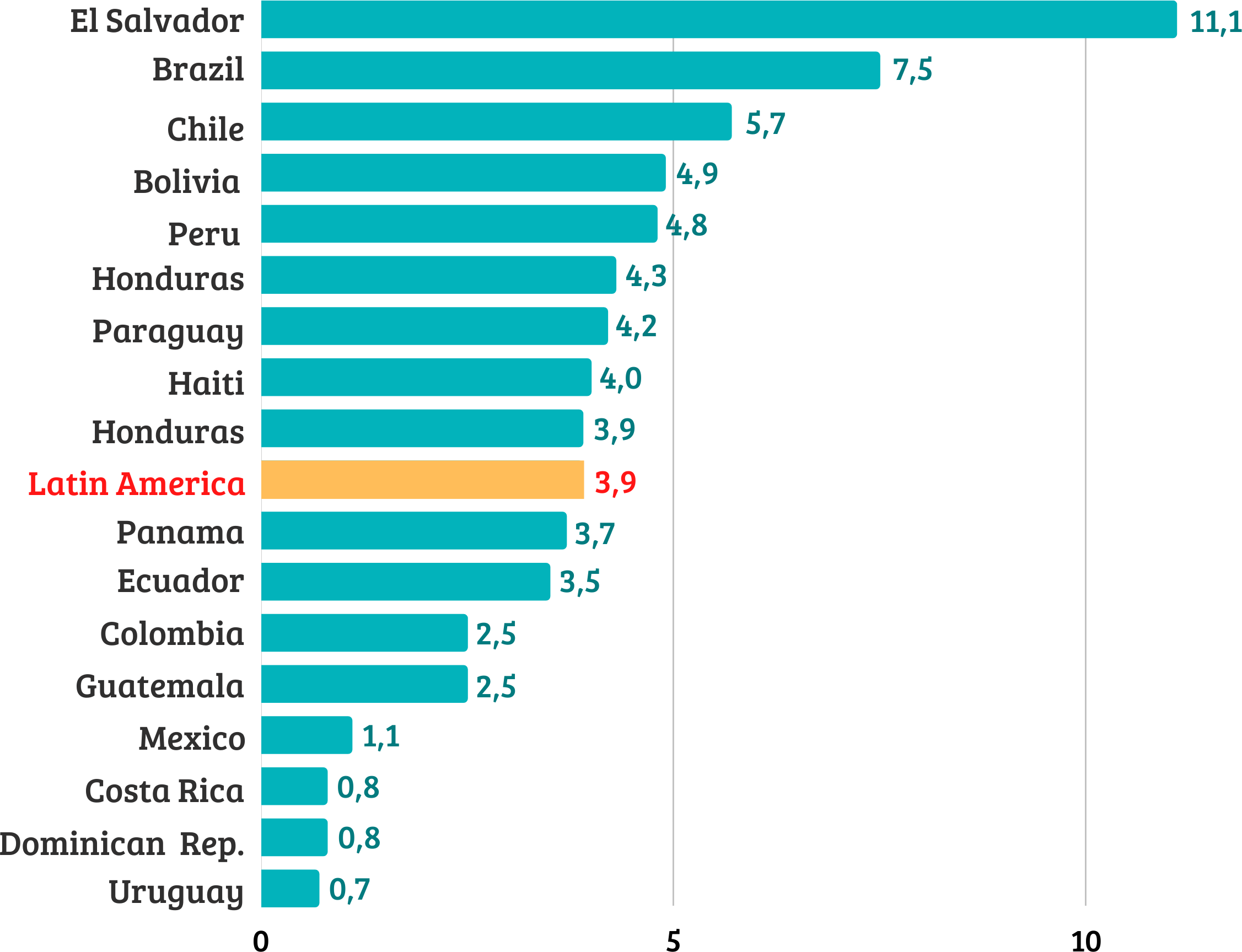

Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, society’s culture, economy, and customs have changed, and the economic sector was one of the most affected. Due to the measures imposed by governments to reduce contagion, several labor sectors had to undergo a virtual adaptation process, resulting in job instability or even job loss [1]. According to the International Labor Organization (ILO), 34 million workers lost their jobs (some of them temporarily). The impact was especially severe in those economies that depend on activities that cannot be carried out remotely [2]. As a result, governments took different measures to mitigate the social and economic effects of the pandemic. These measures can be evaluated through the fiscal effort, calculated using a country’s spending averages, tax relief, and the corresponding liquidity. Thus, a report by the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) shows that countries such as El Salvador and Brazil had a higher fiscal effort index. In contrast, the Dominican Republic and Uruguay had the lowest indexes in the Latin American region(Figure 1)[3].

Fiscal effort in the Latin American region to mitigate the social and economic effects of the pandemic.

The pandemic seriously vulnerated the Latin American population since informality rates (which have increased over the years) are high [4,5]. Extensive compliance with governmental measures and orders to contain the pandemic was not expected because it represented a daily income loss for a large sector of the population [6]. In addition, the prices of healthcare services and drugs to treat COVID-19 were relatively high due to the collapse of health systems within the region and the increase in hospitalizations and patients in intensive care units. All this placed many families in situations of great precariousness [7,8]. Thus, in a context of informality, faced with the need to take care of sick family members and being unable to work because of the containment measures, the absence of work or the risk of losing it represent highly stressful situations that can affect the mental health of workers [9].

There is a validated scale on the perceived job security that Peruvian workers had in the context of movement and work restrictions declared by the government [10]. However, this validation was carried out only in the Peruvian labor context. Although Peru has many similarities with other countries in the region, it does not represent an accurate picture of the region due to cultural differences, the heterogeneous measures dictated by each government, and the labor situation of each country, among others. However, common elements in the realities of Latin American countries allow us to evaluate their idiosyncrasies. For example, the pandemic generated inflation and economic crisis in most countries in Latin America. This resemblance may be because most nascent national industries depend on foreign investment for job creation. In that sense, the impact of the pandemic on the work environment has been very similar among these countries [11]. Therefore, this study aimed to revalidate an ultra-short scale for measuring perceived job security in Latin America.

Methods

Design and population

We performed a multicenter validation study with a cross-sectional design. Due to the restrictions and limitations posed by the COVID-19 pandemic, a non-probability convenience sampling was used for this study. The sample size required a minimum of 15 to 20 respondents for each question; however, the minimum sample size was exceeded. A total of 1953 participants from Peru, Chile, Paraguay, Mexico, Colombia, Bolivia, Panama, Ecuador, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala responded to the survey.

Participants were included if they were over 18 years of age, living in one of the countries participating in this study, and working at the time of the survey. Participants who were suspended due to governmental measures or living in rural areas were excluded because they were difficult to access due to the virtual nature of the survey.

Of the participating countries, Peru contributed the most respondents (1061), followed by Chile (256), Paraguay (176), and Mexico (147). The other countries contributed fewer than 100 respondents. Peru represented the highest number of subjects because it was the most affected Spanish-speaking country in the Latin American region. The population surveyed were workers of public and private sectors working in the urban areas of the largest cities in each country, considering that this is the population that contributes most to the economy. Most respondents were women (56.1%), with a median age of 29 years (interquartile range: 22 to 44 years).

Previously validated instrument

The present instrument aims to revalidate the LABOR-PE-COVID-19 scale [10] applied in Peru during the first semester of 2020 and validated in 332 workers from public and private institutions. In the LABOR-PE-COVID-19 scale, Aiken’s V values greater than 0.70 were obtained. This scale contains four items condensed into a single factor through questions with Likert-type responses, ranging from "strongly agree" to "strongly disagree"regarding the job security perceived by workers during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Procedure

The authors of the project evaluated the LABOR-PE-COVID-19 scale and determined its relevance. Because the project was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, and since some of the participating countries had large numbers of infected and dead, it was decided that the project would be entirely virtual. For this reason, the scale questions were transferred to a Google Forms sheet. The survey was applied between June and August 2020 to those who met the selection criteria. The data were collected at the end of the second wave of COVID-19 in most countries participating in the study. The 1953 responses obtained in the different countries were included. The participants of this study were direct contacts of the medical students from the Latin American Federation of Scientific Societies of Medical Students (FELSOCEM). The latter supported the survey in the different countries that were part of this research. The students contacted the participants through virtual means such as social networks, e-mail, direct messages, or telephone calls. Once they consented to be part of the study, the virtual survey was shared with them through a form on the Google Forms platform. Participants were informed of the study’s objectives, and their consent to participate voluntarily was requested before begging the survey. In addition, it was explained to them that they could withdraw from the survey at any time. The collected data were coded and transferred to a Microsoft Excel 2019 spreadsheet database, where we performed quality control of the responses obtained. Although this scale was validated in Spanish, we translated the instrument into English and Portuguese (Supplementary Files in Notes).

Data analysis

The statistical analyses were carried out in three stages. In the first stage, the items were analyzed through descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation, skewness, and kurtosis), where we considered a cutpoint greater than ± 1.5 for skewness and kurtosis [12]. In the second stage, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed using structural equation modeling (SEM). We evaluated the goodness-of-fit measures through the comparative fit index (CFI), the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), the goodness-of-fit index (GFI), and the adjusted goodness-of-fit index (AGFI). The parameters for the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) and the mean squared error (MSE) were also considered, following the criteria from Hooper et al. [13]. The latter states that a) the values of the comparative fit of Tucker-Lewis, goodness-of-fit, and adjusted goodness-of-fit indexes should be greater than 0.90, and b) the root mean square error of approximation should be less than or equal to 0.08. In the third stage, we calculated construct reliability using McDonald’s omega coefficient [14]. We used the statistical program FACTOR Analysis version 10.1 for the descriptive analysis, the program AMOS version 21 for the confirmatory factor analysis, and the statistical software SPSS version 23.0 to establish reliability.

Ethics

The Research Bioethics Committee of the Universidad Privada Antenor Orrego approved this research by resolution No. 0237-2020-UPAO. In addition, we always respected the participant’s privacy and complied with all the ethical principles of the Helsinki declaration.

Results

Table 1 shows the mean, standard deviation, skewness, and kurtosis values for the four items of the WORK-LATAM-COVID-19 scale. Item four has the highest average score (mean: 2.23) and shows the greatest dispersion (standard deviation: 1.38). The skewness and kurtosis of the four items of the scale are adequate since they do not exceed a range greater than ± 1.5 [10].

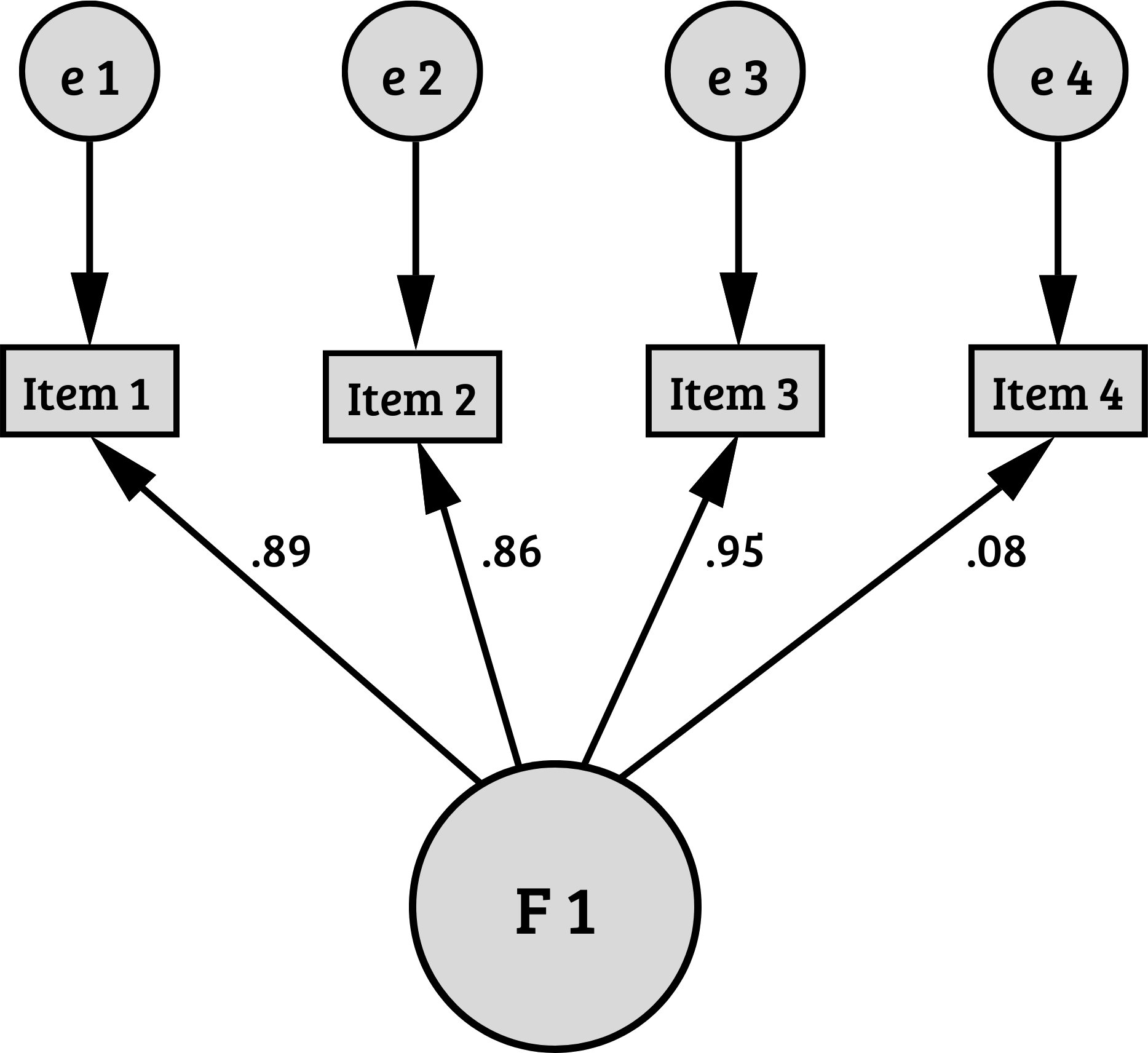

Confirmatory factor analysis

We considered previous evidence to verify the internal structure. Therefore, confirmatory factor analysis was performed with a unidimensional structure, where all four items explained a single factor. The goodness-of-fit measures confirmed the single-factor model (χ2: 7.06; df: 2; p = 0.29; mean square error: 0.015; goodness-of-fit index: 0.998; adjusted goodness-of-fit index: 0.991; comparative fit index: 0.999; Tucker-Lewis index: 0.997; normalized fit index: 0.998; incremental fit index: 0.999; and root mean square error of approximation: 0.036). In summary, the original model of unidimensional structure reported a good fit (Table 2)(Figure 2).

Unidimensional model of the WORK-LATAM-COVID-19 scale.

Finally, the reliability of the WORK-LATAM-COVID-19 scale was calculated using McDonald’s omega coefficient. A value ω: 0.72 (95% confidence interval: 0.69 to 0.74) was obtained, indicating that the scale is reliable. The final scale is shown in Table 3.

Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic profoundly affected many labor, economic and social aspects. Globally, underdeveloped and developing countries have been the most affected. This worldwide emergency is reflected by higher unemployment rates and lower hiring rates [15,16]. Likewise, Latin America has been one of the continents with the most significant impact on the sector regarding hours worked and labor income, after Asia and Europe [16,17]. Similarly, five Latin American countries have exceeded their annual unemployment rate: Brazil, Argentina, Chile, Colombia, and Peru [16,18]. In addition, we can add the fear of losing jobs and the necessity of adapting to new work forms (teleworking). These aspects have brought underlying mental problems, such as depression, anxiety, sleep disorders, and others [19,20,21]. Thus, revalidation of the WORK-LATAM-COVID-19 scale aims to offer Latin America an instrument that objectively assesses workers' perception of their employment and job security. The WORK-LATAM-COVID-19 scale has four items, all grouped into a single factor.

Items four and two assess the respondent’s job insecurity, interpreted as the outcome of the current job or the perceived challenges of a new job in the near future. It has been observed that previous unemployment, for whatever reason, generates fear and uncertainty in the worker [22]. This feeling may be explained by the negative impact of job loss on the individual’s mental health, associated with a decrease in job and life satisfaction, as observed in a study conducted in Canada, Germany, the United Kingdom, and the United States [23]. Moreover, the deterioration caused by a physical disease may further compromise workers' mental health. A stronger relationship between this phenomenon has been observed with arterial hypertension and obesity, in addition to higher consumption of tobacco and alcohol [24,25,26]. It is worth mentioning that, despite attempts to reactivate the economy and employment, according to the ILO, there are about 34 million unemployed people in Latin America [15].

Items three and one are closely related to those mentioned above. They evaluate the possibility and the certainty of losing the current job in the short or medium term, which may be affected by internal and external factors [27]. The internal factors include personal issues and the fulfillment of family roles such as age, gender, poverty, educational level, family support, treatment of family members for COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 pathology, the contagion of COVID-19, private education, payment of debts, taxes, and rent [27,28,29]. Among the external factors, the negative influence of the media, friends, and acquaintances on work experiences during the health emergency (massive suspension of activities, reduction of salaries, looting of banks, shopping malls, and dismissals due to COVID-19, among others) stands out. Among the external factors, the type of work (own or contracted, formal or informal) and the government’s policies on the current economic recovery and mobility restrictions are also considered [15,30].

Another factor that may predispose to unemployment and lack of opportunity is culture. This aspect is especially notorious in Latin American countries, where gender problems create a labor supply gap for women, which reduces their opportunities to obtain a steady income [31,32]. On the other hand, the economic model of each country has determined the severity of the measures applied to contain the pandemic. In those countries with higher per capita income and private investment, the restriction measures (quarantine) have been milder and, consequently, unemployment has not increased dramatically [33]. However, those countries with lower private investment and greater state presence applied stricter quarantines with severe effects on the economy of their citizens [34].

One of the study’s limitations is the selection bias of having a non-random sample (selected by convenience), partially representing the population under study. In addition, the study sample primarily consisted of people living in large cities and did not include people from rural areas. Despite its limitations, this scale can be a starting point for further research scales development in countries that have been part of this study and those within Latin America or other regions that share similarities.

Conclusions

The four-item WORK-LATAM-COVID-19 scale has demonstrated validity in both form and substance.

The confirmatory factor analysis of the internal structure reports a good fit. Likewise, it presented an acceptable Cronbach’s α coefficient, thus evidencing a good level of reliability.

Despite being validated during the COVID-19 pandemic, this scale may also be valid in other situations and emergencies.