Estudios originales

← vista completaPublicado el 25 de julio de 2023 | http://doi.org/10.5867/medwave.2023.06.2681

Traducción al español, retraducción y validación de contenido de la escala Quality of Life in Alzheimer’s Disease en pacientes con demencia Alzheimer

Spanish translation, retranslation, and content validation of the Quality of Life in Alzheimer’s Disease scale in patients with Alzheimer’s dementia

Abstract

Introduction It is estimated that by the year 2050, persons over 60 will account for 22% of the world population. Consequently, the incidence and prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease will increase correspondingly. One of the pillars of the treatment of this condition is to improve the quality of life. In this sense, questionnaires such as the Quality of Life in Alzheimer’s Disease allow us to measure the quality of life in patients and caregivers.

Objective To translate into Chilean Spanish and carry out the content validation of the Quality of Life in Alzheimer’s Disease scale in patients with Alzheimer’s dementia at the Guillermo Grant Benavente Hospital in Concepción, Chile.

Methods Translation, back-translation and content validity were carried out by expert judgment, using Lawshe analysis, pre-test and semantic validation using the respondent debriefing strategy.

Results The translated and retranslated versions were compared with each other and with the original version. Lawshe indicates that a Content Validity Ratio equal 0.49 is adequate to consider the item valid when 15 experts participated in the content validation process, as in our study. The analysis yielded a content validity ratio greater than 0.49 in 11 of the 13 items on the scale. Of these, 8 obtained a value greater than 0.8 and 3 between 0.49 and 0.79. In semantic validation using the respondent debriefing strategy, the scale was applied to five people with Alzheimer’s and their respective caregivers. With the data obtained, modifications were generated in those items that obtained a content validity ratio of less than 0.49.

Conclusions The version obtained in Spanish of the Quality of Life in Alzheimer’s Disease scale is valid from the point of view of its content and equivalent to its original version.

Main messages

- There are no validated questionnaires in Chile for measuring the quality of life in patients with Alzheimer’s disease.

- Here, we present the process of translating the Quality of Life in Alzheimer’s Disease scale into Spanish and validating its content in Chile.

- This study makes the translated instrument available to professionals or researchers, opening opportunities to improve the quality of life in these patients.

- The limitations include those inherent to this type of design since this instrument was originally designed for a context different from ours.

- The Spanish version of the Quality of Life in Alzheimer’s Disease scale is valid regarding its content.

Introduction

It is common knowledge that our population is aging. This has been reported by the United Nations, which estimates that by the year 2050, 22% of the world’s population will be over 60 years of age. In relation to this, the increase in life expectancy is the main risk factor for certain pathologies, such as cardiovascular diseases, osteoporosis, cancer, diabetes, and neurodegenerative diseases [1].

Among neurodegenerative diseases, dementia is among the most prevalent, characterized as a clinical syndrome with progressive cognitive and functional impairment [2]. Alzheimer’s disease is the leading cause of dementia and is considered progressive and non-curable. As a result, this disease significantly affects the patient and their families. Currently, the main treatment of this disease is focused on symptom control in an attempt to achieve better daily functionality, which has been measured in recent studies through the quality of life. However, this concept appeared only at the end of the last century, when studies began to be carried out [3]. Due to the increase in life expectancy, quality of life has not necessarily improved, which is one of the concerns of healthcare systems. Thus, quality of life has become a fundamental aspect to be considered when evaluating their performance.

Given the variety of definitions related to quality of life in health, the definition proposed by Rebecca Logsdon [4], based on the approaches of Lawton [5,6], was used in this study. This refers to the subjective assessment made by an individual regarding:

-

Their skills or competencies to perform in daily life.

-

Their environment.

-

Their psychological well-being.

-

Their perceived quality of life.

Each of these domains is relevant to assess the quality of life of older adults with cognitive impairment. Having questionnaires to account for these will make it possible to evaluate the functionality of these individuals and their responses to different types of interventions.

From a psychometric point of view, the Quality of Life in Alzheimer’s Disease (QoL-AD) scale is one of the most widely used instruments in the world, proving valid and reliable. In her study, Rebecca Longsdon found that the QoL-AD had good internal consistency, with correlations between the items and the total score. For patients, these ranged between 0.40 and 0.67, and for caregivers, between 0.34 and 0.63. In both cases, Cronbach’s α was 0.88 and 0.87, respectively [7]. On the other hand, test scores correlated significantly with the mini-mental (r = 0.24) for patients; daily life activities (r = -0.33 and r = -0.3, respectively); Hamilton depression scale (r = -0.43 and r = -0.25); geriatric depression scale (r = -0.56 and r = -0.14); and pleasurable events scale (r = 0.30 and r = 0.41) [7].

It should be noted that similar results were found in 2002 in 177 patients, where Cronbach’s α obtained was 0.83 to 0.90. It correlated as expected with daily life activities (r = -0.31 and r = -0.37), depression (r = -0.22 and r = -0.23), physical performance (r = 0.22 and r = 0.43), objective burden (r = -0.21 and r = -0.52), subjective burden (r = -0.19 and r = -0.53), and caregiver depression (r = -0.48), among others [4]. This scale has been adapted and validated in different countries for different languages, finding values similar to those reported in the original study. There are versions available for the United States, Germany, France, Spain, Italy, Portugal, the United Kingdom, the Czech Republic, Switzerland, Turkey, Egypt, China, Korea, Japan, and Thailand. At the regional level, its validation was performed in Brazil and Mexico [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27].

In Chile, there are currently no validated questionnaires for measuring Alzheimer’s disease patients' quality of life. This type of measurement complements healthcare assistance. Particularly for Alzheimer’s disease, Chile has incorporated it into the new health guarantees in the National Dementia Plan, estimating that approximately 20 000 patients with Alzheimer’s disease or other dementias will be covered [28]. Therefore, measuring these patients' quality of life as a part of their care and follow-up becomes particularly relevant.

This study aims to validate the QoL-AD questionnaire developed by Logsdon in terms of its content to provide a tool to assess the quality of life in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. It should be noted that this is the first stage of a larger project aimed at the adaptation and psychometric validation of this scale in the Chilean population.

Methods

Type of study

The design of this study responds to the content validity of the scale.

Content validation process

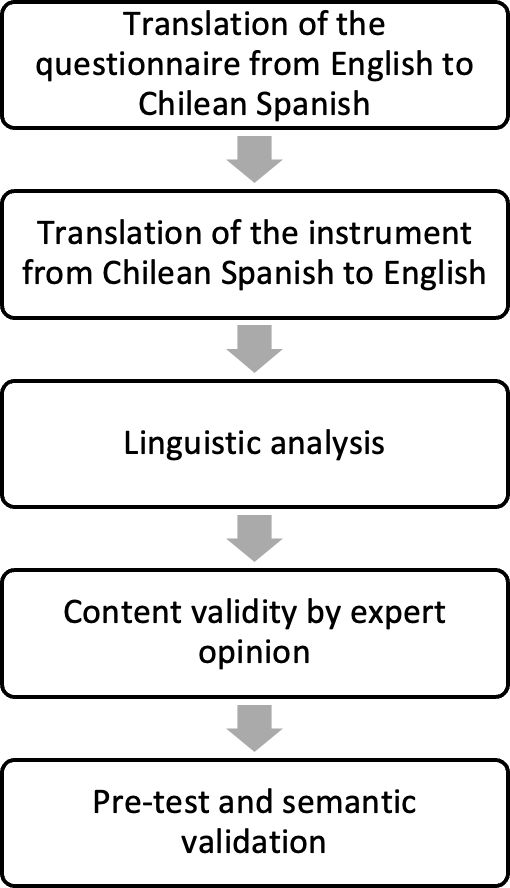

For content validation, the process was structured in three stages:

-

Translation-retranslation.

-

Content validity by expert opinion, using the Lawshe analysis [29].

-

Pre-test and semantic validation using the respondent debriefing strategy [30] (Figure 1).

Stages of translation and content validity analysis of the QoL-AD scale.

Source: Prepared by the authors.

Translation and retranslation

Four certified translators and two linguists from the University of Concepcion collaborated in the translation and retranslation of the questionnaire. The purpose of this process was to translate into Chilean Spanish the test in its two versions, one for the patient and the other for the caregiver, as well as the instruction manual for its application. Two bilingual professionals with expertise in Spanish and English carried out the translation independently. One was familiar with the instrument (its contents and objectives), and the other was not. Subsequently, both translations were sent randomly to two other translators who translated the questionnaire into English. Two linguistic experts also reviewed the first translation of the test to ensure that it was culturally equivalent.

Content validity by expert opinion: Lawshe analysis

In this phase, a validation of the items as indicators of the quality of life construct represented by the QoL-AD scale was carried out.

For this, a consensus method was used through expert opinion. Content validity refers to the adequacy with which a measure assesses a domain of interest [31]. One of the problems of conceptualizing validity as correlation is the fact that the appropriate criterion measure must be found. This means that criterion data obtained reliably and validly is needed. In these questionnaires, the score indicates what the test seeks to evaluate and is not a predictor of criteria other than the test. From this perspective, validity refers to the fact that the items that make up the questionnaire are representative of what they are intended to evaluate. This concept is called content validity. Using experts to assess the items' relevance and representativeness is intended to prevent the questionnaire from having biased content. As can be seen, a test is biased if it does not adequately cover the domain it intends to measure or includes unnecessary questions to correctly assess the domain [31]. Fifteen professionals with expertise in dementia participated as judges: a general practitioner, a psychiatrist, two physicians participating in the dementia program in primary care centers, two speech therapists, and nine adult neurologists. The lead researcher contacted each of them by email, where they were sent instructions for their role, requesting objectivity in the evaluation of the tests and confidentiality in the handling of information. Each of them was given a form as a specification guideline. In it, they had to evaluate the general appearance of the questionnaire and its instructions and state whether they agreed or disagreed with the content and format of the questionnaire. They were also asked to give an opinion on its grammar, syntax, wording, and response formats.

Once the forms were obtained from the 15 judges, the responses were entered into an Excel spreadsheet, assigning a value of "1" when there was agreement that the item was representative of what it was intended to measure and "0" when the item was considered inadequate to measure the dimension of which it was an indicator. A score ranging from 0 to 15 points could be obtained for each item.

For the analysis of content validity, the proposal of Lawshe (1975) [29] was used, which states that this is determined by the degree of overlap that occurs between the contents of the test and the contents of the characteristic that it is intended to measure, expressed through his formula of the content validity ratio (CVR):

Where: ne = number of judges who consider the item valid; N = total number of judges.

Lawshe suggests that a content validity ratio equal to 0.49 is adequate to consider the item optimal when 15 experts have participated in the content validation process, as in this study. All those items that obtain a value lower than 0.49 should be analyzed and improved according to the judges' suggestions.

Pre-test and semantic validation (respondent debriefing)

Once the scale was obtained from the judges' analysis, it was subjected to a semantic validation process using the respondent debriefing method. For this purpose, a pre-test was conducted on 10 people, five with Alzheimer’s disease and their respective caregivers. Each of them was asked to answer the test. Then they were given a semi-structured interview to obtain their opinion on the test; they were asked if they understood the question as a whole and if they understood all the vocabulary, and if they would make any modifications to the question. To ensure that the people selected had characteristics equivalent to those in which the psychometric validation study will be carried out, they were selected using the same inclusion and exclusion criteria.

The following were considered inclusion criteria: having been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease, age greater than or equal to 60 years, and Minimental Test between 0 and 29 points. Exclusion criteria were other types of dementia, severe intellectual impairment, diagnosis of major depressive disorder, or chronic psychotic disorder. On the other hand, for caregivers, the inclusion criteria were being a permanent caregiver and being 18 years of age or older.

Instrument description

The QoL-AD is characterized by two versions of 13 dimensions each, in which each item is an indicator of the quality of life domain. These have a Likert-type response format with four options (poor, fair, good, and excellent). One version is to be answered by the patient and the other by the caregiver. Both scores are summed, and the final result is obtained, from which the total score is determined (the higher the score, the higher the quality of life). For this validation, authorization to use the licensed original version of the QoL-AD scale from June 2019 was acquired through the eProvide platform (Online Support for Clinical Outcome Assessments, registry number 4955).

On the other hand, the mini-mental test [32] was also used. A neurologist conducted a clinical interview with the five selected patients with Alzheimer’s disease to develop the semantic validation stage to safeguard the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Results

Translation - retranslation

The translated and retranslated versions were compared with each other and with the original version. Then, the research team conducted an analysis, arriving at a first consensus draft of the questionnaire. This was reviewed by two experts in linguistics and Chilean Spanish. This resulted in the first version that was submitted to the experts' opinion (Table 1).

Content validity by experts' opinion

Fifteen experts participated in the process, obtaining responses and comments for each of the 13 items of the questionnaire. As a criterion for item acceptance, a minimum Lawshe content validity ratio score of 0.49 [29] was used. Consequently, any item with a score equal to or higher than this value was considered acceptable. The analysis obtained through Lawshe’s content validity ratio yielded a value greater than 0.49 in 11 items. Of these, eight obtained a value greater than 0.8, and three were between 0.49 and 0.79 (Table 2).

Only two items obtained a content validity ratio value lower than 0.49, item 4 and item 13, corresponding to the domains of "living conditions" and "life in general", respectively.

Regarding item 4, "Living conditions" ("What can you say about your living conditions? How do you feel about the place where you currently live? Would you rate it as bad, fair, good or excellent?"), the judges' recommendations were mainly focused on the broad nature of the term "living conditions", which contrasts with what is ultimately asked, which is the patient’s living conditions. Some of the judges' comments illustrating this were:

-

Neurologist; "the indicator has two questions in one: the first aims at living conditions, a broad concept that encompasses various aspects (environmental, economic, psychic, etc.); anyone could interpret it as the quality of life. The second is a specific question referring to the physical place that orients the dwelling and its surroundings (a more concrete question). If this is what you want to evaluate, I suggest changing the first question to a neutral statement and not a question about (or in relation to) living conditions".

-

Neurologist; "living conditions is much broader than the housing situation that ends up being asked; it can be confused with the economic question that is asked later. In addition, perhaps this question is better placed at the end of the questionnaire".

-

General practitioner; "since we are talking about relationships and economic situations later, I would put the dimension as the housing situation. As an example: regarding where you live, do you feel it is adequate for you? Does it make moving around and carrying out your usual tasks easy? Would you classify it as bad, regular, good, or very good?".

-

Speech therapist; "living conditions is a broad indicator, followed by a specific one such as the place where you live. It is possible to have good living conditions but a non-optimal housing reality, so it can be misleading".

-

Speech therapist; "I find 'living conditions' too broad; does it refer to material conditions? Support network? Health? If the question of living conditions were more precise, I would separate it from the actual place of living as it points to something different."

Regarding item 13, referring to the dimension "Life in general" ('"What would you say about your life in general, when you think about your life as a whole, how do you feel about it, would you say it is bad, fair, good or excellent?"), the judges stated that it is a question that could be answered by item 9 of the "Yourself" dimension so that it could lead to confusion. Comments illustrating this were:

-

Neurologist; "difficult to differentiate this from the 'yourself' question as to be different indicators".

-

General practitioner; "can be confusing and can be assimilated to the 'yourself' item. It may be necessary to incorporate the possibility of describing the item if the person requests it: how do you feel when you think about your life now, considering different aspects: emotional, personal development, family, etc.".

-

Speech therapist; "the concept of life is already broad enough to follow it from the word 'general'. I would word it as: What do you think of your life when you think of it as a whole?".

Semantic validation (respondent debriefing)

For semantic validation, the respondent debriefing method was used, for which the scale was applied to five people with Alzheimer’s disease (four females and one male) and their respective caregivers. The persons with Alzheimer’s disease had an average age of 79.6 years and an average mini-mental test score of 16 points. In the case of the caregivers, the average age was 55 years. The approximate time of application of the scale was 15 to 20 minutes per patient and caregiver.

In this process, during the scale application, the greatest uncertainties of the patients occurred with item number 2, on the "Energy" dimension ("How do you feel about your energy levels? Do you think it is bad, fair, good or excellent?"), where three people with Alzheimer’s disease expressed doubts. For example, two of them pointed out "I don't understand what you call energy"; and another asked, "Do you mean energy for walking?". The second item that presented difficulties was item number 9, on the "Yourself" dimension ("How do you feel about yourself? When you think about yourself as a whole and the different aspects of your life, would you say you feel bad, fair, good or excellent?"). In this regard, two people with Alzheimer’s reported feeling confused, as they found that this item had similarities with the question asked in item number 13, alluding to the dimension "Life in general". This was consistent with what the judges reported in their analysis, as seen in the previous section. Concerning the caregivers, none of them stated that they did not understand the questions.

Considering all of the above, modifications were made to those items that obtained a content validity ratio lower than 0.49, as well as to those that, despite having obtained a score higher than this, were observed by the judges and by the patients in the respondent debriefing process. Thus, a second version of the scale was obtained (Table 3).

Discussion

Alzheimer’s dementia is a highly prevalent neurodegenerative disease, for which the main therapeutic approach lies in symptom control and improving the quality of life of patients, their caregivers, and their families. Given this, it is imperative to have valid instruments to measure these patients and their caregivers' quality of life to assess therapeutic interventions.

The process of validating the content of a scale involves different stages and challenges. The relevance of detailing each of them lies in highlighting that the translation of a questionnaire is not limited to a simple language challenge but involves a more complex process with important methodological decisions.

The first version of the questionnaire, obtained from the translation and retranslation process and the linguistic analysis, was the initial phase that allowed the experts' opinions and the work with linguistic specialists. Each item was identified and verified whether it represented the theoretical domain of interest in this phase. This and the respondent debriefing process provided the necessary basis and support to develop the modifications to the first translated version of the questionnaire. This resulted in a second version, which is the one proposed for the psychometric validation process of this scale.

Few psychometric validation instruments are published with the analysis of this content validation process, which gives additional value to this study.

Most of the items evaluated were adequate in their intended measurements. However, we found terms that caused conflict in representing what they were intended to measure. Concepts such as living conditions, life in general, and energy. A conflict that in the analysis is explained by the cultural differences between the instrument’s country of origin and ours, where different attributions are assigned to the concepts in question. For this reason, it is imperative to analyze each conflicting concept from a cultural and contextual point of view to avoid losing the meaning of this scale, which was made for a particular context. As a work team, this led us to agree upon an interpretative analysis to avoid ideas that the participants did not understand and could affect the instrument’s validation work and complement it with others of more common use and knowledge in our environment. We emphasize that most of the observations and modifications proposed by the experts' work are consistent with those observed by the patients.

Among the strengths of the content validity analysis, the fact that experts in the field, with vast experience in clinical and academic settings, participated in the study stands out.

This study also makes the translated instrument available for professionals and researchers, providing opportunities for new research or interventions aimed at improving the quality of life of these patients.

Among the limitations of this type of design, we find those inherent to this type of design when adapting this instrument for a specific context and purpose.

Finally, it is important to emphasize that this is an ongoing process in which the instrument will be observed in all phases of the psychometric validation process.

Conclusions

The results of this study allow us to state that the content of the instrument is valid.