Estudios originales

← vista completaPublicado el 10 de abril de 2025 | http://doi.org/10.5867/medwave.2025.03.3033

Estudio retrospectivo sobre las diferencias en los tiempos de espera al tratamiento en pacientes de cáncer de mama chilenas en relación con su tipo de previsión de salud

Retrospective study on disparities in time-to-treatment by health insurance system in Chilean breast cancer patients

Abstract

Introduction Breast cancer is the most common malignancy in the Americas, and the second leading cause of cancer death. Disparities in the time to treatment can significantly impact patient outcomes and typically affect lower socioeconomic individuals and/or ethnic minorities. Our study sought to evaluate disparities in time to treatment at three health institutions in Chile according to their type of health insurance (public or private).

Methods Our study analyzed a database of breast cancer patients diagnosed between 2017 and 2018. Analyses included descriptive statistics and a linear regression model that incorporated clinical and demographic variables. Additionally, using a proportional risks model, we analyzed the association between clinical variables and mortality.

Results Public health insurance (National Health Fund, FONASA) was associated with longer time-to-treatment and extended treatment times versus private health insurance (Social Security Institutions, ISAPRE; p < 0.0001). As expected, a more advanced stage at diagnosis was associated with lower survival. Our proportional risks model found that age was a predictor of breast cancer mortality in stage II patients. Also, total treatment time significantly increased the risk of breast cancer mortality in stage I patients. Conversely, total treatment time did not affect mortality on stages II or III.

Conclusions We found significant disparities in the time to treatment of Chilean breast cancer patients using FONASA versus private ISAPRE. FONASA patients experience delays in the initiation of treatment and longer total treatment times compared to their private insurance counterparts. Finally, longer time-to-treatment was associated with more advanced stages and increased mortality.

Main messages

- Longer waiting time-to-treatment leads to poorer outcomes for breast cancer patients, typically affecting ethnic minorities and lower income groups.

- Our study assessed the time to treatment in Chilean breast cancer patients, comparing public versus private health insurance users.

- Public health insurance was associated with delays and prolonged total treatment times. Longer time to treatment was associated with more advanced cancer stages and higher mortality.

- The study was restricted to three cancer centers, which may not be representative of the entire country. Specific clinical characteristics of patients, like molecular subtypes and comorbidities, were unavailable.

Introduction

Worldwide, more than 2.3 million cases of breast cancer were diagnosed in 2019, causing over 685 000 deaths. Therefore, breast cancer remains a leading cause of cancer death for women [1,2]. The development of more effective strategies for breast cancer detection and prevention over the past few decades has led to a significant increase in survival rates. However, disparities in access to high-quality detection assays for timely diagnosis and treatment in certain subpopulations or demographic and ethnic groups can reduce their survival [3].In the United States, breast cancer mortality rates among African American women are 40% higher than those of White Americans. Although this can be partially explained by biological factors such as higher incidence of more aggressive, higher histological grade, and higher prevalence of estrogen receptor-negative tumors, it is also associated with socioeconomic factors that reduce access to high-quality, timely treatments. Similarly, a study in Canada assessed breast cancer mortality trends during the period 1992 to 2019 and confirmed a higher breast cancer mortality in women from lower socioeconomic levels [4]. Previous studies demonstrate disparities in the time to treatment among Black women, with delays in the time from diagnosis to surgery, initiation of chemotherapy, and radiotherapy. Importantly, a prolonged time to treatment is associated with poorer overall survival and breast cancer-specific survival in newly diagnosed patients [5].

As occurs worldwide, breast cancer is the leading cause of cancer death in Chilean women. In recent decades, Chile has experienced rapid economic growth. Unfortunately, progress has come at the price of profound social inequities and disparities in access to healthcare [6]. The Chilean health system comprises a public health insurance system (FONASA), which provides coverage to 76.5% of the general population, and a private insurance system (ISAPRE), that covers approximately 15.4% of the population [7]. The remaining percentage corresponds to armed forces and other insurance services [8].

In 2005, the Chilean Ministry of Health implemented the “Garantías Explícitas en Salud” (GES) program that guarantees universal access, funding, and quality medical care for FONASA and ISAPRE users [9]. The program covers several malignancies, including breast cancer, and establishes a 30-day window between breast cancer diagnosis and primary treatment. It is noteworthy that the GES offers a free mammogram to women aged 50 to 59 years old every three years. The program also states that adjuvant treatment for patients should begin within 20 days following a physician's indication [10].

As pointed out above, it is well established that delayed surgeries are associated with reduced overall survival and increased breast cancer mortality [11]. In contrast, literature on the optimal time to start adjuvant chemotherapy is rather inconsistent. While the European Society of Medical Oncology guidelines recommend starting adjuvant treatment within two to six weeks after surgery, the introduction of personalized treatments, which include genomic studies, has increased the time to surgery for newly diagnosed patients [12]. Similarly, studies on the timing of radiotherapy initiation are controversial, with some reports suggesting that longer intervals between surgery and radiotherapy are associated with adverse outcomes [13,14,15,16,17,18,19], while other studies have shown no association with loco-regional recurrence-free survival [20,21,22,23].

Therefore, we sought to quantify and compare the time-to-treatment for breast cancer patients at three Chilean hospitals, including the time from diagnosis to surgery, from surgery to adjuvant chemotherapy, and from diagnosis to radiotherapy according to their health insurance (private or public).

Methods

Study population and data sources

This retrospective cohort study was conducted between 2016 and 2017. Data were collected from three reference centers in Chile: Cancer Center from Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, which is a private health center located in the Metropolitan Region; and National Cancer Institute, also located in the Metropolitan Region, and the Valdivia Base Hospital, located in southern Chile in the Los Rios region. The study population included adult women with a confirmed diagnosis of either in situ or invasive breast cancer based on initial diagnostic biopsy, who received chemotherapy or radiotherapy after undergoing surgery. This study excluded: patients with secondary cancer, patients undergoing palliative treatment with radiotherapy, pregnant women, cases without definitive biopsy details, patients with fibroepithelial tumors, patients treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy, and patients with incomplete data on treatment and pathological stage.

Study variables

The variables included in the analysis were age at the time of diagnosis, the patient’s health insurance system (FONASA and ISAPRE), geographical location, the health center where treatment was received, and breast cancer stage (stages I, II, and III) at the time of diagnosis. We defined the time of the initial diagnostic biopsy as week zero. Then we determined the duration of the time intervals between the main therapeutic milestones: diagnosis to surgery, surgery to adjuvant chemotherapy, surgery to radiotherapy, and diagnosis to radiotherapy. The extension of treatment was calculated from diagnosis to the end of treatment or death. Patient follow-up was 75 months, unless the patient died before that period.

Survival and statistical analyses

We estimated Kaplan-Meier survival curves to assess the survival function of patients according to their pathological stage. We used the log-rank test to determine if there were statistically significant differences in survival among the different cancer stages. We adjusted the proportional hazards Cox models to assess the association between breast cancer clinical factors and overall mortality. We included pathological stage, age, district, and the time elapsed since treatment as covariates to control for their potential effects. For each Cox model, we verified the assumption of proportional risks using the Schoenfeld test of residuals and charts. We calculated hazard ratios along with confidence intervals for each independent variable. Before adjusting the Cox model, we performed a stepwise analysis to select the most significant variables. We applied both forward and backward methods to optimize the selection of variables. We also evaluated multicollinearity among covariates using the variance inflation factor to ensure the model was not affected by strong linear relationships among independent variables. To confirm the robustness of our findings, we performed sensitivity analyses by varying the cutoff values for time categories until treatment and examining alternative models. For statistical analyses, we conducted descriptive analyses for all variables, stratified by healthcare insurance. The data were summarized as means ± standard deviations for continuous variables and as numbers (%) for categorical variables. Differences in characteristics between patients who used public vs. private health insurance were assessed using a Kruskal-Wallis test (for continuous variables) and a Chi-squared test (for categorical variables). Fisher’s exact test was used when the sample size was small in any category to ensure the validity of the results. Additionally, mean differences were calculated for time intervals (FONASA vs. ISAPRE), along with 95% confidence intervals. We used a multiple linear regression model to evaluate the relationships with the total duration of treatment (in weeks), defined as the time from diagnosis to the end of the primary treatment, as the dependent variable. The health insurance system used (FONASA and ISAPRE) and pathological stage (I, II, and III) were the independent variables in the model. The model enabled us to estimate the independent effect of each variable, adjusting for the other covariates. For analysis, we generated dummy variables using ISAPRE as the reference for health insurance and stage I as the reference for pathological stage. The associated results are reported as hazard ratios with 95% confidence intervals. All results were obtained with R software (v 4.3.2). We considered the level of 5% as significant.

Results

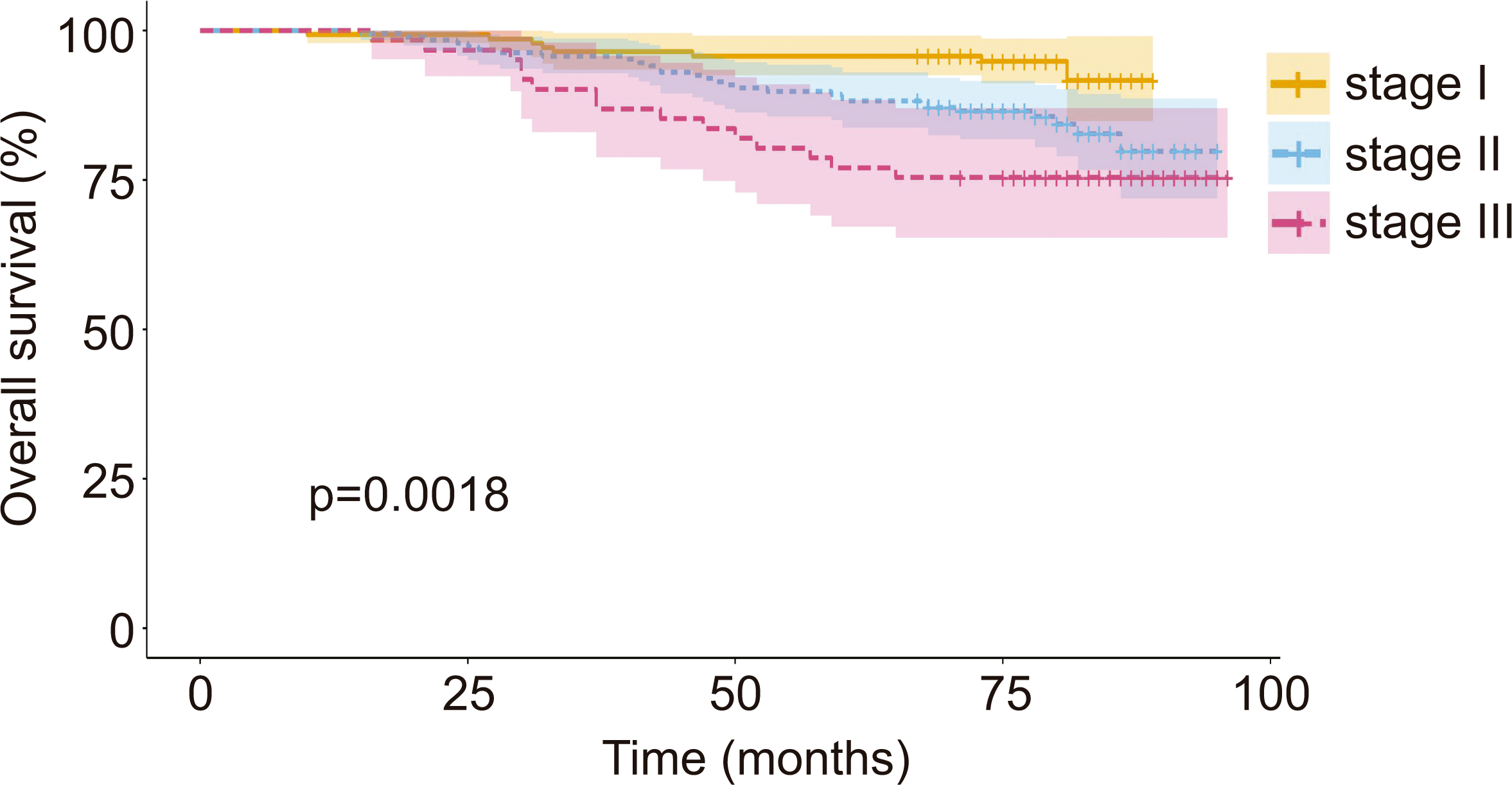

A total of 389 patients with breast cancer were included in the study. Participants were divided according to their health insurance system; n = 336 for FONASA (public insurance) and n = 53 for ISAPRE (private insurance). Table 1 summarizes basic clinical and sociodemographic characteristics of participants according to the health insurance system. While mean age at diagnosis and vital status did not show statistically significant differences when comparing FONASA versus ISAPRE, all ISAPRE patients were treated at the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile cancer center, a center located in the Metropolitan district, which represents a significantly higher proportion than FONASA. Additionally, FONASA patients showed a lower proportion of stage I but a higher percentage of stage III compared to ISAPRE. As pointed out earlier, the vital status of patients did not show significant differences between FONASA and ISAPRE. However, after stratifying by stage, we found a progressive reduction in the overall survival probability at higher breast cancer stages (94%, 84%, and 75% for stage I, II, and III, respectively; public health patients showed a lower proportion of stage I but a higher percentage of stage III compared to ISAPRE. As pointed out earlier, the vital status of patients did not show significant differences between FONASA and ISAPRE. However, after stratifying by stage, we found a progressive reduction in the overall survival probability at higher breast cancer stages (94%, 84%, and 75% for stage I, II, and III, respectively; Figure 1).

Overall survival curve by pathological stage at diagnosis from initial diagnostic biopsy.

Then, we quantified the time interval between the initial diagnosis (biopsy) and subsequent therapeutic interventions by type of health insurance. As shown in Table 2, the time intervals from diagnosis to surgery, from surgery to radiotherapy, and from diagnosis to radiotherapy were significantly longer for FONASA versus ISAPRE (p < 0.0001), with estimated differences of 54.45 days, 67.18 days, and 115.85 days, respectively. Note that for the time interval from surgery to adjuvant chemotherapy, the ISAPRE group had fewer than 10 observations, which precluded us from obtaining a reliable estimate of the mean difference and 95% confidence interval (Table 2). However, we evaluated the difference in data distribution using the Kruskal-Wallis test (p = 0.103).

Our multiple regression model showed that public insurance users (FONASA) had a longer treatment duration compared to private insurance users (ISAPRE), with an average increase of 15.43 weeks (95% CI: 10.97 to 19.90; p < 0.001). Additionally, the duration of treatment for patients diagnosed at stage II was 4.71 weeks longer (95% CI: 1.61 to 7.81; p = 0.0029) compared to those diagnosed with stage I disease. In this regard, patients diagnosed with stage III disease displayed the longest treatment duration, with an increase of 27.44 weeks (95% CI: 22.82 to 32.06; p < 0.001) compared to stage I patients (Table 3). These values represent adjusted differences in treatment duration, controlling for the effects of other variables in the model.

Next, we performed a multivariate analysis using Cox models stratified by health insurance type Table 4). We found significant associations in FONASA, while the associations in ISAPRE are very limited given the small number of events. In FONASA, pathological stage was strongly associated with mortality. Stage II patients had a 243% increase in their risk of death versus stage I (HR: 3.43, p = 0.013), while stage III was associated with a 364% increase (HR: 4.64, p = 0.0106). In ISAPRE, HR values display similar trends (stage III HR: 3.73). However, these values did not reach statistical significance, likely due to the low number of events in this cohort (p = 0.182). On the other hand, age at diagnosis showed a 2.7% increase in the risk of death for each additional year in FONASA (HR: 1.027, p = 0.0275), whereas in ISAPRE, age was not significant (HR: 1.013, p = 0.73). We did not find a significant association with district of treatment (Los Rios) and mortality in either group. Likewise, total treatment time did not have a clear effect on survival (FONASA HR: 1.006, p = 0.53; ISAPRE HR: 1.037, p = 0.126).

Finally, we performed an analysis of proportional risks stratified by breast cancer stage to assess the impact of age and total treatment time on breast cancer mortality. Table 5 shows that age did not have a significant effect on breast cancer mortality for stages I or III. However, age was a predictor of breast cancer mortality in stage II patients, with a 3.7% increase in mortality risk per year of age. Also, total treatment time significantly increased the risk of breast cancer mortality in stage I patients. Hence, every additional week in the diagnosis-to-radiotherapy interval rises by 4.4% the risk of mortality of these patients. In contrast, total treatment time did not affect breast cancer mortality for stages II or III.

Discussion

Our study found significant disparities in the time to treatment of Chilean breast cancer patients using public (FONASA) or private (ISAPRE) health insurance systems. In this regard, FONASA patients experience a delay in the start of their treatment and longer total treatment times compared to patients with private insurance. In turn, longer total treatment times are associated with more advanced stages and mortality.

Several retrospective studies in the United States have demonstrated that Black and Hispanic women experience prolonged breast cancer treatment delays compared to White women [5]. Although these studies suggest the etiology of disparities in the time to treatment is multifactorial, they demonstrate that the insurance status plays a key role. For example, a phase 3 clinical trial that included more than 2600 breast cancer patients found that longer total treatment times were more frequently observed among Black, younger, and lower-income patients. Notably, this study also demonstrated these patients were more likely to have Medicaid (typically offered to lower-income families or individuals), be uninsured, and have a higher stage at diagnosis [24]. Similarly, a study found that the percentage of Medicaid and uninsured patients increased proportionally to the time to surgery [25]. In line with these studies, we found that the proportion of stage III patients was significantly higher in FONASA vs. ISAPRE (17.26% vs. 5.66%). Conversely, the percentage of stage I patients was higher in ISAPRE vs. FONASA (49.06% vs. 34.23%). As pointed out, Chile has a dual healthcare system, where national public health insurance (FONASA) coexists with private insurance providers (ISAPRES). Worldwide, other countries, such as the United Kingdom and the Netherlands, also have dual systems and coexistence between public and private sectors. However, unlike these countries, private insurance in Chile is optional and not complementary to public insurance. This generates segregation based on income. Indeed, ISAPRES that seek to minimize their risks (costs), concentrate on younger, higher-income, working-age males who can afford premium health care plans. In contrast, FONASA is primarily used by lower-income, older individuals with higher risk factors and comorbidities 26]. Therefore, it is reasonable to speculate that prolonged time to treatment and extension of treatment in public system users could be associated with their socioeconomic status.

Within Latin America, healthcare systems from Brazil and Mexico share some of the challenges of the Chilean system, such as public/private insurance segregation and profound socioeconomic inequalities that impact the time to treatment and survival of breast cancer patients in the public system [27,28]. On the one hand, the healthcare system in Mexico is fragmented into multiple insurance plans [29]. Notably, 57.3% of the Mexican population lacks access to employment-based health care insurance [30], and 15% have no healthcare access [28]. A qualitative study conducted in four Mexican states found low levels of trust in both the public and private healthcare systems. Some of the reasons given by participants include long waiting times, poor service, high out-of-pocket costs, and lack of medications. Regarding breast cancer, local reports demonstrate that Mexican patients usually experience delays in the diagnosis and start of treatment [31,32]. In fact, over 45% of patients are diagnosed at advanced stages of the disease. One of these studies found that longer intervals to breast cancer care were more frequent in younger, lower socioeconomic status individuals who lived outside Mexico City. Similarly, our proportional risk analysis revealed that age was associated with a higher risk, but only among stage II patients (Table 5). In contrast, the geographical location (Metropolitan or Los Rios district) in our study did not affect patients’ risk. More recently, studies in Mexico have reported major delays and shortening of breast cancer treatments for patients because of the COVID-19 pandemic [33].

On the other hand, Brazil is the largest country in Latin America. Like Chile, Brazil has a dual public and private healthcare system. Although the Brazilian law establishes a maximum of 60 days between breast cancer diagnosis and the start of treatment, several studies demonstrate that most patients experience significant delays in the start of treatment [34]. A cross-sectional study conducted between 1998 and 2012 revealed that treatment delays were more frequent among non-whites, patients with stage I/II disease, those with lower educational levels, and those aged 50 years or older [27]. A study by dos Santos compared the time to treatment at two referral hospitals and demonstrated that the privately financed institution had a shorter time to treatment compared to the publicly funded institution [35]. In terms of mortality, patients who used public health insurance had a poorer prognosis and lower breast cancer-specific survival versus patients who used private insurance [36]. A retrospective study conducted in Southeastern Brazil, which included over 12 000 cases, concluded that a longer time to treatment is associated with socioeconomic, clinical, and healthcare infrastructure [37]. A similar retrospective study included more than 78 000 breast cancer cases and found that treatment was delayed (> 60 days from diagnosis) for 51.8% of patients. Delays were more pronounced among older patients who lived a considerable distance from treatment centers [38] More recently, a couple of prospective studies sought to determine factors associated with increased time to treatment, and found that the place of residence, stage at diagnosis, and age (≥ 60 years old) were relevant factors [38,39].

Longer intervals between breast cancer detection and initiation of therapy may affect patient prognosis and disease progression, causing treatment complications and increasing the risk of death [40]. Indeed, studies demonstrate that increased time to treatment is associated with reduced survival in stage II and III breast cancer [41]. Accordingly, a recent systematic review suggests that surgery should ideally occur within 90 days of diagnosis, and chemotherapy should be given within 120 days from diagnosis [42].

Interestingly, our findings suggest that total treatment time, rather than time to treatment, is associated with survival only in stage I patients. Regarding treatment duration, the real-world median duration of treatment varies significantly depending on the tumor site, stage, and treatment modality. While the expected duration of chemotherapy and radiotherapy can be estimated, there is less clarity around the time between treatment modalities. This non-treatment time may account for post-surgery, post-chemotherapy, or radiotherapy recovery and reflect the toxicity associated with cancer treatments. The delays in access to treatments, due to resource constraints, may also contribute to this and could explain the greater extension of treatment observed in our study for FONASA versus ISAPRE [43]. Another aspect that could explain the increase in treatment duration in patients using public health insurance is the existence of a longer delay from the onset of symptom manifestation to their first consultation with a healthcare professional, or from the first consultation to an accurate diagnosis due to the scarcity of medical hours, which can result in diagnosis and treatment at more advanced stages. Results obtained in this study showed that a higher percentage of patients are diagnosed at stages II and III (advanced stages) in FONASA compared to ISAPRE. This late diagnosis can lead to an increased risk of death.

Our study has several limitations. First, it includes patients from three national reference centers, both public and private, located in the capital and other regions. Therefore, the results may not be representative of the national reality. Secondly, information on some key factors associated with mortality from breast cancer, such as tumor biological subtypes and patient comorbidities, was not available; further research is planned. In this way, the results obtained by this study support the fact that in Chile, access to cancer diagnosis and treatment presents significant disparities between the public and private healthcare systems. While the public system faces longer waiting times, limitations in infrastructure, and insufficient resources, the private system offers faster, higher-quality healthcare, albeit at a considerably higher cost. In response, initiatives such as the National Cancer Plan proposed by the Ministry of Health in 2018 are generating public policies aimed at reducing healthcare disparities for breast cancer patients.

Conclusions

Chilean breast cancer patients who use the public insurance system experience significant delays receiving cancer treatments and longer waiting times versus patients who use private insurance. This includes longer time intervals, such as from diagnosis to surgery, from surgery to radiotherapy, and from diagnosis to radiotherapy. These delays are associated with more advanced cancer stages at diagnosis (which translates into a poorer prognosis) and higher mortality, evidencing significant disparities between the Chilean public and private healthcare systems.