Estudios originales

← vista completaPublicado el 22 de septiembre de 2025 | http://doi.org/10.5867/medwave.2025.08.3086

Comparación del perfil de egresos hospitalarios entre nacionales y migrantes internacionales: una década de contrastes y desafíos sanitarios para Chile (2013 a 2022)

Comparing the profile of hospital discharges between nationals and international migrants: a decade of contrasts and health challenges for Chile (2013 to 2022)

Abstract

Introduction Migration is a recognized social determinant in the world. Chile has experienced an abrupt increase in immigration in recent years, demanding, among other things, health care services. The aim of this study was to compare the profile of hospital discharges between nationals and migrants in Chile.

Methods An observational study was conducted using routinely collected health data, analyzing the database of hospital discharges of the Ministry of Health in the decade between 2013 and 2022.

Results There were 16 013 995 hospital discharges (95% Chilean and 2% foreigners), with higher proportions in the north of the country. Departures of foreigners show a steady increase, rising sixfold over the decade (from 0.7 to almost 4%). There are significant differences in the distribution by sex (Chileans: 41.2% men/58.8% women; foreigners: 22.4% men/77.6% women). According to age, in both populations, the highest frequency of discharges occurred between 20 and 39 years of age (30.3% in Chileans and 68.7% in foreigners). Death at discharge occurred in 2.4% of Chileans and 0.9% of foreigners. The most frequent diagnosis of discharge was the pregnancy, delivery and puerperium’ group, with significant differences (20% Chileans and 58.5% foreigners). Chileans have a higher proportion of cardiovascular diagnosis (12.1% versus 7.5%) and respiratory diseases (13.2% versus 7.5%), while foreigners have a higher proportion of trauma, poisoning and other external causes (13.9% Chileans versus 22.1% foreigners).

Conclusions The growth of the immigrant population has increased the demand for hospital resources, requiring adjustments in planning and resource allocation. It is suggested that inclusive policies focus on prioritizing maternal-child care and accident and injury prevention for migrants.

Main messages

- The central problem is the rapid increase of the migrant population in Chile, with a growing impact on the demand for health care, especially in northern regions.

- The study brings novelty by analyzing a full decade of the hospital discharge database of the Department of Health Statistics and Information of the Chilean Ministry of Health, comparing migrants and nationals, including the period of the pandemic and one year after.

- A key limitation is the lack of detailed social and clinical variables in the database, which prevents an in-depth characterization of patients and their care, and the impossibility of estimating specific population rates.

- The main finding is that discharges of migrants increased sixfold, with a predominance of young women and diagnoses related to pregnancy, childbirth and puerperium, as well as trauma in men, which suggests prioritizing inclusive policies in maternal and child health and accident prevention.

Introduction

Migration is a recognized social determinant in the world [1,2]. The conditions surrounding the migration process make this population potentially vulnerable and their cross-border movement has a great impact on public health [2,3]. Although Chile has limited official statistical data on the prevalence of diseases or health conditions among immigrants, the Ministry of Health began to take special protective measures for this population in 2016. In March of that year, Supreme Decree No. 67 was published, which sets the circumstances and mechanism for accrediting people lacking resources as beneficiaries of the National Health Fund (FONASA, the public insurance), adding the condition of immigrant people lacking resources without documents or without residence permits. This provides health coverage to the immigrant, placing them on an equal footing with Chileans [4,5]. Migrants who have an employment contract or who contribute independently have access to health care through the National Health Fund or the system of Private Security Health Institutions, both the contributor and his or her direct family members and dependents [4]. In this way, progress has been made in equitably improving access to health services, in accordance with legislation, national practices, and various international human rights instruments ratified by Chile [3].

It was in 2016 that the identification of the migrant population was incorporated into the Monthly Statistical Records in primary care. Likewise, guidelines are given to strengthen the registration of migration status in secondary and tertiary care (hospital discharges).

According to data from the National Institute of Statistics, 1 462 103 migrants were living in Chile in 2021 [6]. This figure shows a progressive increase in the number of people born outside the country, from 0.8% in 1992 to 7.5% in 2020. In addition, immigration experienced new growth in 2022, reaching a proportion of 8.7% of the total population [6], primarily comprising young people [7].

Regarding the origin of immigrants in our country, the Socioeconomic Characterization Survey 2022 indicates that immigrants of Venezuelan origin increased from 2% in 2013 to half of the total number of immigrants in the country that year [8]. The immigrant population is mainly concentrated in the Metropolitan Region, which gathers 65% of them. However, although the regions comprising the so-called Northern Macrozone (Arica and Parinacota, Tarapacá, Antofagasta, Atacama and Coquimbo) are home to a smaller number of the country’s immigrants (15%), it is in these territories where the proportion of immigrants with respect to the total population reaches the highest figures. Particularly striking is the case of Tarapacá, where 17.5% of its inhabitants (one in six) are of foreign origin [8].

With respect to the use of health services, it has been evaluated whether there are differences in the probability of utilization between the two populations [3,9]. However, it has been found that the probability of hospitalization is lower in immigrants compared to nationals. This is explained by the lower age of migrants, the "healthy migrant" theory, having less access to health care or differences in the cultural valuation of the disease, among other reasons [10].

In Chile, few studies analyze the health aspects related to migrants. The present work aims to determine the profile of hospital discharges in Chile, comparing the discharges of nationals with those of foreigners, over the decade from 2013 to 2022. Its purpose is to contribute to future health policies. It is hypothesized that there are differences in the characteristics of hospital discharges between migrants and Chileans. For example, in terms of distribution by sex, age, types of diagnosis, and frequency according to regions of the country.

Methods

An observational study was conducted with routinely collected data from the Hospital Discharge database of the Department of Health Statistics and Information for the years 2013 to 2022 of the Chilean Ministry of Health. It corresponds to a comparison of total annual hospital discharges between the national and international migrant population in Chile in the period studied.

Sources of information

All hospital discharges for the decade from 2013 to 2022 were analyzed, corresponding to 16 013 995 discharges. The data on hospital discharges are compiled by the Department of Health Statistics and Information of the Chilean Ministry of Health, covering information from all public and private centers in the country. The comparison variable was the nationality of the individual, whether Chilean or foreign. A hospital discharge was considered to correspond to the national population if the patient indicated having Chilean nationality, and to international migrants if the person declared another nationality. The variables compared were age group, sex, region of residence (Figure 1), insurance (public insurance, National Health Fund or private insurance), type of facility (public or private), days of stay, discharge diagnosis (according to diagnostic groups of the International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision, ICD-10) and discharge condition (alive or deceased).

Political map of Chile, regions, and borders.

Data analysis

The complete database for the study was extracted from the Department of Health Statistics and Information’s web page using a Python program, which enabled the retrieval of basic tables in accordance with the set objectives. These tables were then transferred to Excel for analysis. We excluded 417 380 hospital discharge data records that did not include the variable "nationality", corresponding to 3% of the total number of discharges during the decade. With the cleaned data for each of the tables, we present absolute and relative frequencies (percentages) of hospital discharges according to nationality and their distribution by year, sex, age group, region of residence and the 10 main groups of diagnoses (according to ICD-10), which correspond to 88.5% of the causes of discharge for the decade. In addition, prevalence ratios were calculated (relative frequency of hospital discharges in the period, among Chileans versus foreigners, for age groups and discharge diagnoses), with their respective 95% confidence intervals, using the Epidat 4.2 calcupedev v10 tool [11].

Results

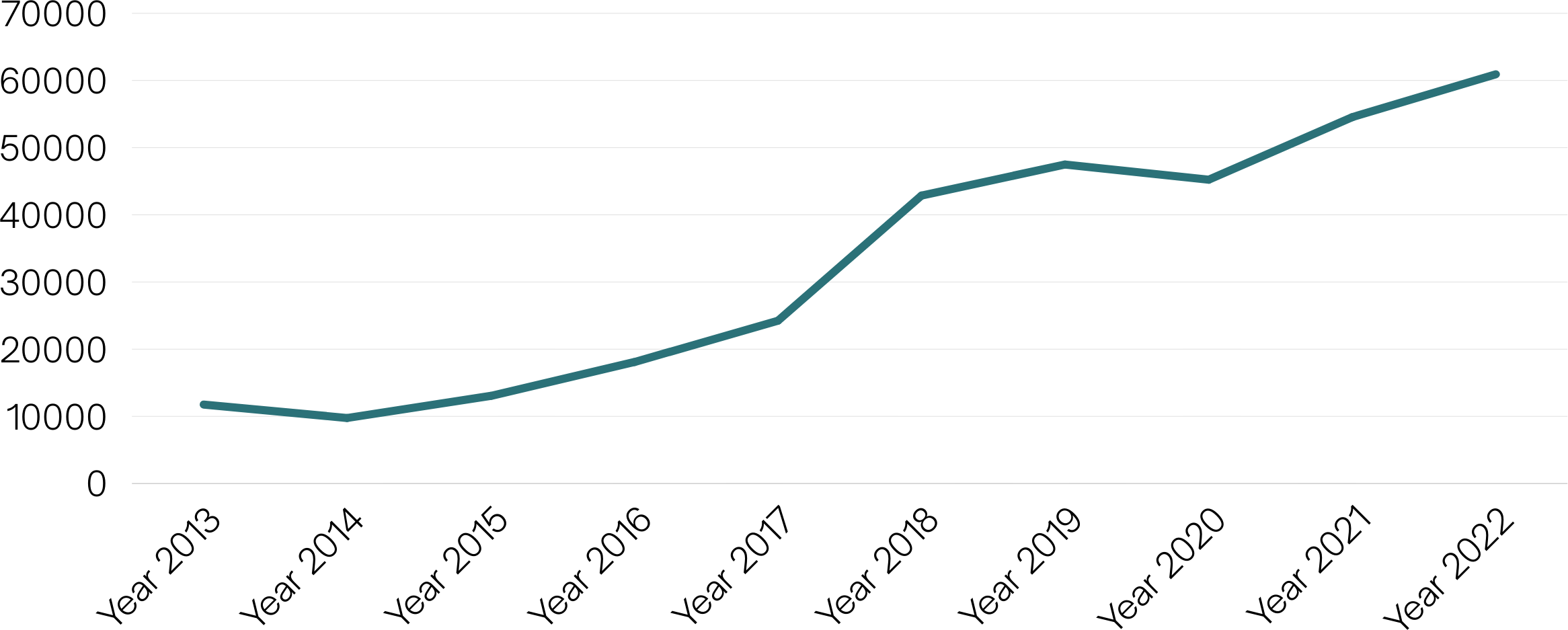

A six-fold increase in hospital discharges of foreign residents was observed between 2013 and 2022 (Table 1 and Figure 2).

Evolution of hospital discharges of foreigners, Chile 2013 to 2022.

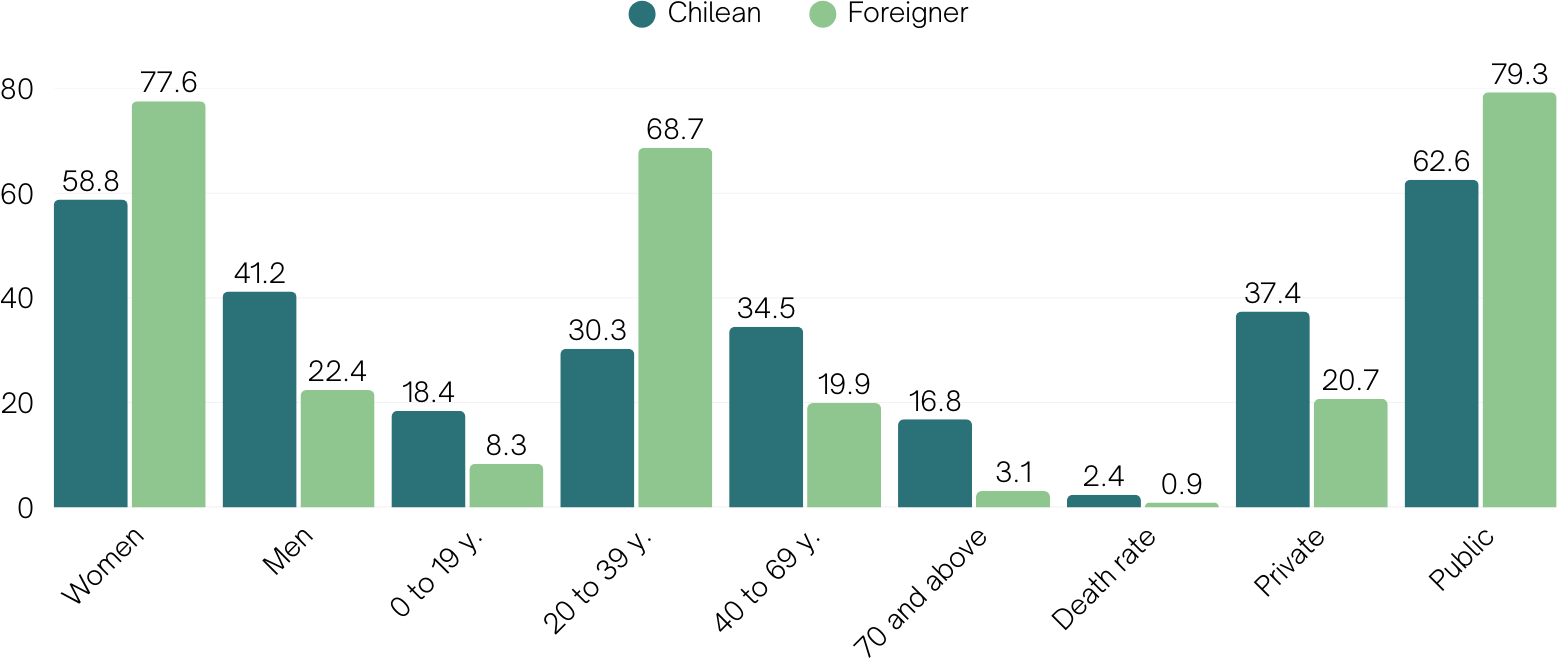

As for the distribution by sex, in both population groups, women tend to be hospitalized more than men. Of these, more than half (58%) were related to reproductive diagnoses (women of childbearing age, tables 1 and 2).

Table 3 shows the age distribution of discharges of foreigners, in which young adults predominate, with more than two thirds of people between 20 and 39 years of age. While only one third of the national discharges correspond to these ages, and 28% of the Chilean discharges are over 60 years of age (Table 3 and Figure 3).

Relative frequency (%) of hospital discharges by sex, age group, and type of hospital in Chileans and foreigners, Chile, 2013 to 2022.

It was observed that the highest proportion of outflows of foreigners is concentrated in the regions of Tarapacá, Antofagasta and Arica-Parinacota (Table 4), areas with a high influx of immigrants due to the existence of border crossings, both legal and irregular [8].

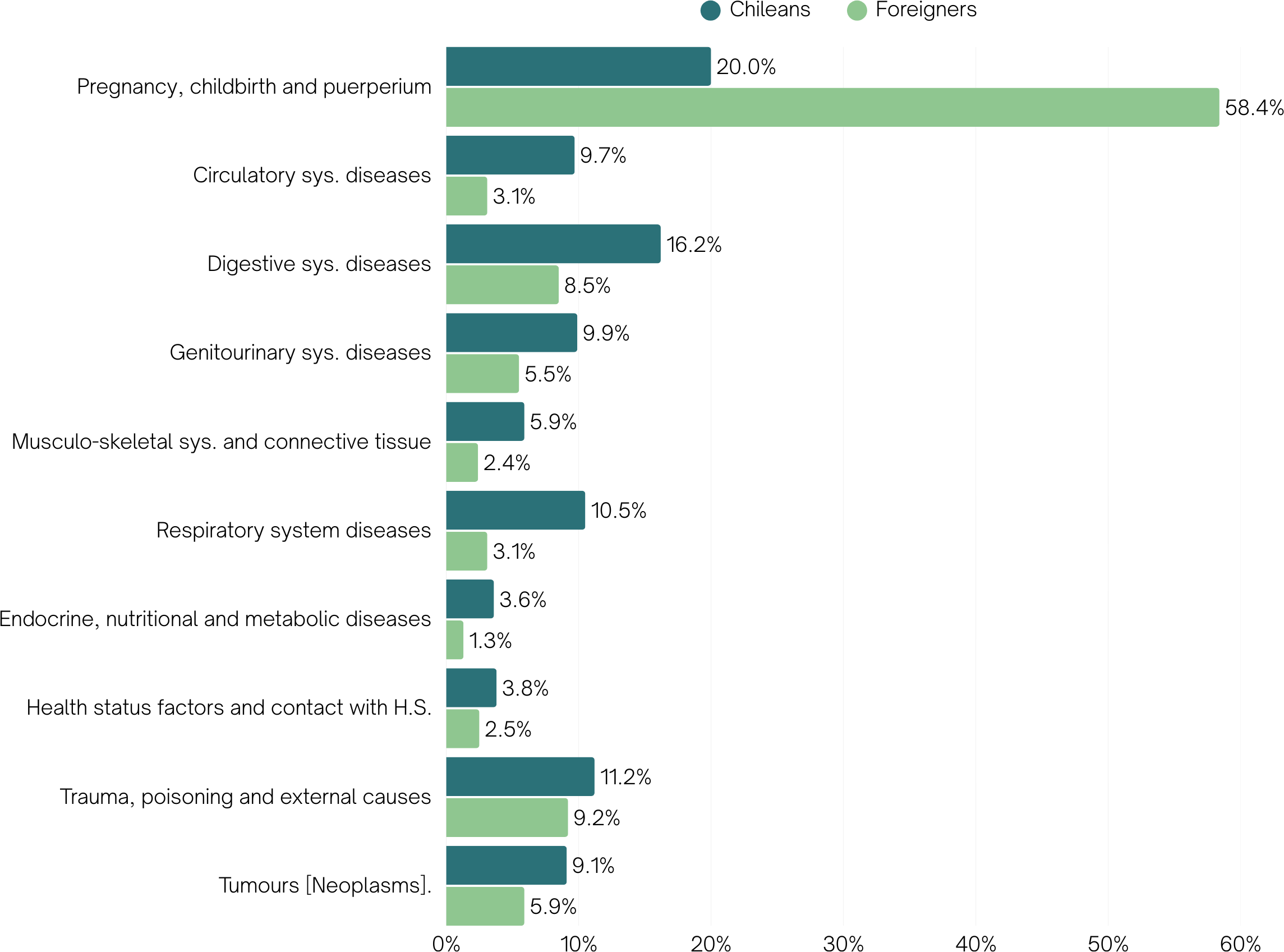

The main discharge diagnoses in both types of residents are those related to "pregnancy, childbirth and puerperium", although among foreigners this diagnosis is almost three times higher than in Chileans (Figures 4 and 3). Among women, foreigners double the causes related to pregnancy, childbirth and puerperium, while Chilean women quadruple the frequency of discharges due to causes of the circulatory, respiratory and musculoskeletal systems (Table 2). Among men, trauma is the main cause of hospitalization among foreigners, almost doubling the frequency of Chileans, who are hospitalized mainly for diseases of the digestive system. The data also show that, excluding obstetric diagnoses, cardiovascular and respiratory diseases are more prevalent among Chileans, while trauma and poisoning are more common among foreigners. These differences were significant (data not shown).

Relative frequency (%) of hospital discharges according to diagnostic group in Chileans and foreigners, Chile, 2013 to 2022. Sys, System; H.S, Health services

The main provider corresponded to public hospitals, which accounted for 79.3% of the discharges of foreigners, a figure much higher than that of Chileans. The National Health Fund was the main insurer (data not shown).

In the period studied, 62.7% of Chilean discharges originated in hospitals belonging to the National Health Services System and 37.4% in other types of establishments (clinics or private hospitals). In the case of foreigners, 79.3% were discharged from hospitals belonging to the National Health Service System and 20.7% from other types of facilities (Figure 3).

Regarding the duration of hospitalization for Chileans and foreigners, it was observed that there were no significant differences in the average number of days of stay (data not shown). However, there is great variability in the maximum number of days of hospitalization at discharge. In the case of Chileans, the maximum number of days varied between 16 381 and 22 186. In the case of foreigners, it varied between 303 and 3654 (data not shown). Very long stays are related to mental health diagnoses (data not shown).

Regarding the condition at discharge, 2.4% of Chilean hospitalized patients died during the decade studied, while only 0.9% of foreigners died (Figure 3). Hospital mortality was significantly lower in foreigners compared to Chileans, being concentrated in younger age groups among foreigners (data not shown).

Discussion

The results of the study show that there are differences in the profile of hospital discharges between the local population and international migrants, confirming the hypothesis put forward and being consistent with the scarce literature on this subject. The main differences are because migrants who are hospitalized are younger and have a higher proportion of women compared to nationals. Strongly related to the above, the proportion of hospitalizations for reproductive causes is higher among foreign women. This finding is consistent with previous publications [2,5,9,10]. On the other hand, the frequency of admissions due to trauma in foreigners is significantly higher compared to nationals. Additionally, the proportion of admissions for circulatory and metabolic diseases is higher among nationals compared to foreigners. Previous studies describe, for example, that chronic diseases such as diabetes are less frequent in migrant populations with origins in communities that maintain traditional diets [13]. Other studies report a 39% lower frequency of chronic diseases and lower frequency of cancer-related discharges among migrants compared to Chileans [7,14].

As previously mentioned, a high percentage of hospital admissions among immigrants are related to pregnancy, childbirth and puerperium, indicating a high demand for reproductive health services. This could be explained by the feminization of migration in Latin America, where migration of women of childbearing age is high [5]. This focus on reproductive health, together with a lower use of services for chronic diseases, could reflect both the specific needs of a mostly young population of reproductive age and possible barriers in access to preventive and long-term care. This contrasts with the Chilean population, in which chronic diseases have a greater presence, reflected in hospital discharge diagnoses. The data suggest that, although immigrants arrive in the country in relatively good health, their health needs evolve rapidly, posing a challenge to the sustainability of the health system if not adequately managed.

One aspect of interest is the observation on the higher frequency of trauma among foreign males, a situation found in previous studies, linking this report with work-related accidentability [9]. The study of the labor force among international migrants in Chile indicates that, over the decade from 2006 to 2017, the educational and qualification level of this population increased. However, these people work in less qualified sectors and with lower incomes [3]. The authors outline the following as causal factors: the difficulty of validating academic degrees and qualifications, as well as a lower capacity for quotas in the productive sectors [3]. This study identifies differences between Chilean and foreign workers. The duration of formal jobs is shorter for foreigners, and they also tend to work more hours per week than nationals [3]. Other factors that lead to greater labor vulnerability are discrimination, language limitations, informality, and overeducation, among others [15]. Several studies relate aspects of labor vulnerability in migrants with health effects, demonstrating the need for public policies on occupational safety to reduce occupational risks in migrants [15,16,17].

The profile of hospital discharges reflects, in some way, the health status of the population. The differences found between foreigners and nationals suggest that migrants are younger and healthier than nationals. International evidence suggests that, in addition to having the intention to migrate, one must possess sufficient physical capacities to undertake the migratory process. Thus, based on the hypotheses of "natural selection", age structure differences (younger migrant population than the local population) and lack of information on the part of immigrants who may be in worse health situations, we can affirm that empirical studies have repeatedly recognized the so-called "healthy migrant effect" [18]. This phenomenon is related to lower self-reporting of health problems and even lower prevalence of chronic diseases compared to the local population. Despite this phenomenon, some studies indicate that immigrants are more likely to become ill and die in the immediate post-migration period than individuals from the receiving country.

Furthermore, the effect of the healthy migrant disappears, on average, after 10 to 20 years in the receiving country. This period may decrease in the case of immigrants who are in a situation of socioeconomic vulnerability and who experience poverty, discrimination, lack of social and health protection, labor and spatial social exclusion, among other manifestations [5,10]. The above could lead to a change in the characteristics of migrant hospitalizations as the time of residence in our country elapses, this being modulated by the conditions of vulnerability of this population group.

In general terms, the growth of the immigrant population has led to a greater demand for hospital resources, making visible the need for adjustments in the planning and allocation of resources in the most affected regions [4,19]. Although the number of hospital admissions of immigrants has increased significantly in the last decade, these show a concentration in reproductive diagnoses and a lower proportion of admissions for chronic diseases and hospital mortality, compared to that observed in the Chilean population. This could suggest that the newly arrived immigrants, for the most part, may be young and in better general health. However, this rapid growth has also increased pressure on health resources, implying that the Chilean health system faces several challenges.

One of the main challenges is the response capacity of an already deficient hospital infrastructure, especially in the northern regions of the country, where there is a high concentration of immigrants. In addition, migration raises the need to improve the training of healthcare personnel in intercultural care, as the cultural and linguistic diversity of the immigrant population can make it challenging to provide efficient and culturally appropriate healthcare services [20]. Another significant challenge is the integration of immigrants into the public health system, particularly for those who lack documentation or a regularized immigration status. This limits their access to health care and can lead to untreated health problems that worsen over time. Finally, the planning and equitable distribution of financial and human resources is a constant challenge, as the system must adapt quickly to demographic changes and ensure that both the immigrant and local populations receive quality healthcare without affecting the sustainability of the healthcare system.

The study has the strength of having analyzed all hospital discharges in Chile over a decade, obtained from an official and reliable source, such as the Department of Health Statistics and Information. Therefore, no biases that could invalidate the results obtained can be glimpsed. Likewise, the published information is updated, including the two years of the COVID-19 pandemic (2020 and 2021) and one year after this event (2022). The study highlights the limitations inherent in analyzing routinely collected data. First, the database of hospital discharges has a limited number of variables, which do not allow us to delve into the social characteristics of the people who are hospitalized, such as legal status (in the case of migrants), educational level, public health insurance coverage (National Health Fund, groups A, B, C or D), employment status or occupation, among other social factors. Nor is it possible to delve into the procedures or therapies that each hospitalized person has received, or the costs involved in each hospitalization. Likewise, since this is a record of discharges, the same person may have been registered more than once during the period studied. This implies that the figures reported give an idea of the general characteristics of hospitalizations, but cannot be extrapolated as rates to specific population groups.

On the other hand, the records of hospital discharges reflect those cases of morbidity that were hospitalized, without incorporating all the care provided in open care facilities (emergency consultations and morbidity at the primary level, secondary level or private system). Despite the limitations mentioned above, the study makes a contribution, considering that previous studies date back to the previous decade (2012) [9,10]. The limited evidence available suggests that further research on the subject is warranted.

Conclusion

According to the information presented here, the results are of interest for the formulation of inclusive health policies, especially in the regions of Tarapacá, Arica, and Parinacota, as well as the Metropolitan region. Along these lines, we propose some ideas for public policies to be recommended for the healthcare of the migrant population.

Firstly, it is essential to maintain and facilitate access to the public health system, as it is the primary system used by migrants. This can be achieved by expanding access routes and reducing administrative obstacles.

In addition, it is necessary to strengthen primary care and emergency care in the municipalities with the highest concentration of foreigners, adjusting the per capita and promoting integration through cultural mediators.

Likewise, specific sexual and reproductive health programs should be developed in these regions, together with child care, for migrant women and families, given that most hospital admissions are due to reproductive causes. Additionally, there is a higher proportion of hospital admissions in the pediatric population compared to the Chilean population.

Similarly, it is necessary to incorporate migrants into the systems of surveillance and prevention of occupational accidents and diseases, due to the high frequency of traumatisms in young male migrants, probably associated with precarious working conditions.

Finally, it is necessary to strengthen hospital management with a focus on migrants, incorporating intercultural training programs, maintaining the migratory variable in registration systems, and incorporating clinical audits to identify barriers to care and opportunities for improvement in the health care of migrants.

All these policies require accompanying resources, both financial and human, that facilitate their implementation and integration of interculturality into healthcare.