Estudios originales

← vista completaPublicado el 14 de enero de 2026 | http://doi.org/10.5867/medwave.2026.01.3155

Neurofibromatosis tipo 1 en Ecuador: correlaciones genotipo-fenotipo a partir de una serie de casos

Neurofibromatosis Type 1 in Ecuador: genotype-phenotype correlations from a case series

Abstract

Introduction Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) is a multisystemic genetic disorder caused by pathogenic variants in the gene, characterized by variable clinical manifestations such as pigmentary abnormalities, neurofibromas, skeletal dysplasia, and tumor predisposition. However, genotype–phenotype correlations remain insufficiently explored, particularly in underrepresented populations.

Methods Three unrelated Ecuadorian pediatric patients with a presumptive diagnosis of NF1 underwent detailed clinical evaluation, next-generation sequencing (NGS), using the TruSight Cancer panel, and ancestry analysis based on 46 ancestry-informative insertion–deletion (InDel) markers. Variants were classified according to ACMG/AMP guidelines using the Franklin and Variant Interpreter platforms, which incorporate in silico prediction tools to assess variant pathogenicity.

Results Three distinct pathogenic variants were identified: one nonsense (p.Arg1534Ter) and two missense (p.Gln20His, p.Asp1644Asn). Clinical findings included early-onset orbital plexiform neurofibroma, multiple café-au-lait macules, axillary/inguinal freckling, radial bone dysplasia, cutaneous neurofibromas, and prepubertal gynecomastia. All patients exhibited predominantly Native American ancestry. analyses predicted a pathogenic classification of all variants. Early pigmentary signs, present in all cases, served as key diagnostic indicators.

Conclusions This case series expands the mutational and phenotypic spectrum of NF1 in a pediatric Ecuadorian cohort. Findings underscore the diagnostic value of early pigmentary signs and highlight less commonly reported manifestations such as radial bone dysplasia and prepubertal gynecomastia. Integrating molecular diagnostics with early clinical evaluation may enable earlier and more precise diagnosis, guiding personalized management strategies. Further studies should investigate genotype–phenotype correlations and the influence of ancestry on NF1 expression.

Main messages

- Three pediatric cases with distinct pathogenic neurofibromatosis type 1 variants were characterized, integrating clinical, molecular, and ancestry data.

- Findings expand the mutational and phenotypic spectrum, highlighting rare features such as radial bone dysplasia and prepubertal gynecomastia.

- Early pigmentary signs proved to be key diagnostic indicators, even in infancy, supporting early molecular testing.

Introduction

Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) is a neurocutaneous disorder that affects approximately 1 in 3000 individuals [1]. Clinical manifestations of NF1 may vary significantly, even among relatives. The disease is characterized by the presence of Lisch nodules on the iris, café-au-lait spots, and cutaneous neurofibromas that may extend deeply along peripheral nerves and can form large tumors in regions of the head, face, trunk, and limbs [2]. Additionally, patients with NF1 may experience other conditions such as learning deficits, autistic traits, and depression [1]. Individuals with NF1 have an 8 to 13% increased risk of developing malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors [3].

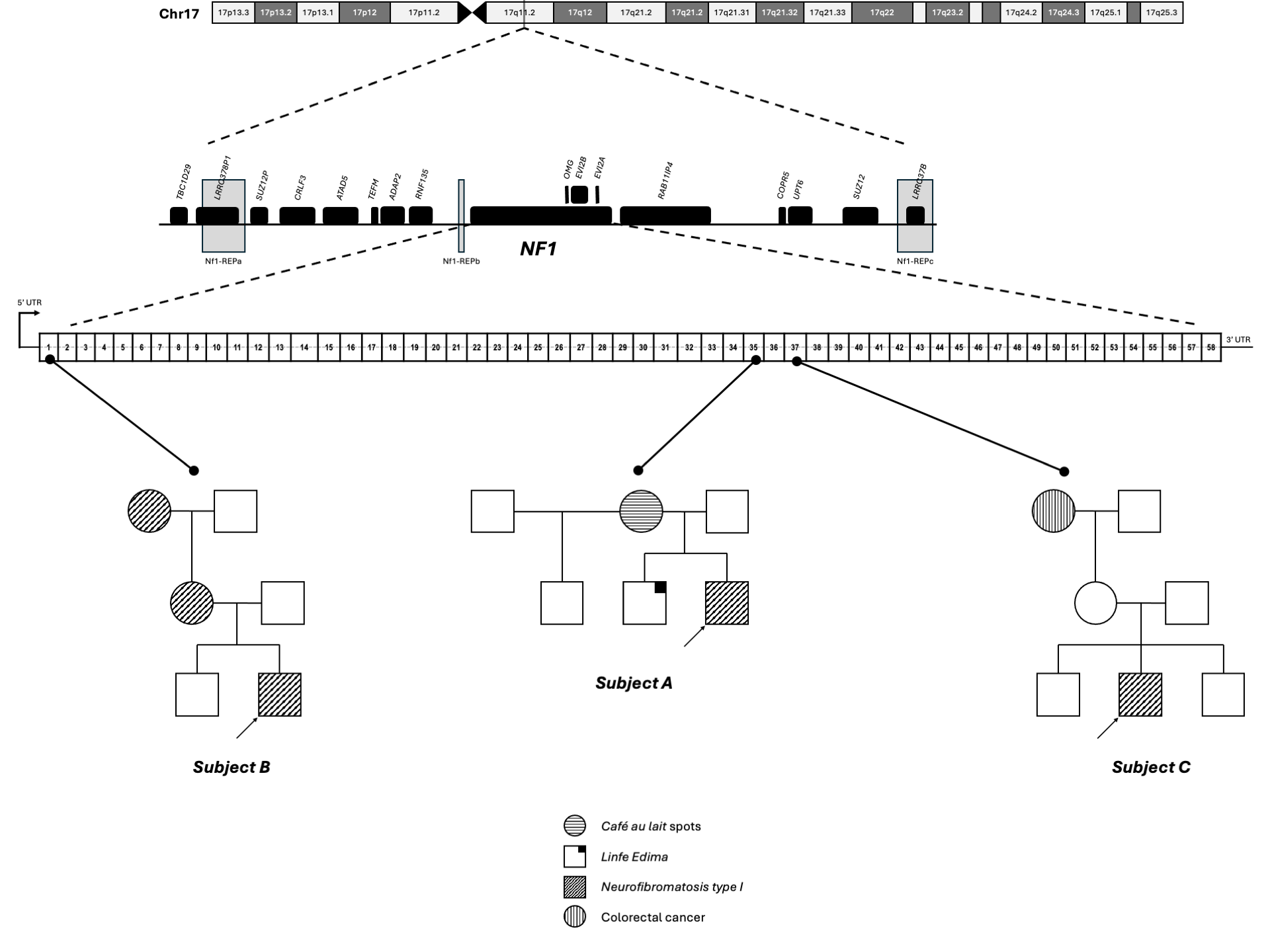

NF1 results from pathogenic variants in the NF1 tumor-suppressor gene located on chromosome 17q11.2, which comprises 58 constitutive and 4 alternatively spliced exons [3]. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) analyses have determined that the pathogenic mutation rate is 92.1% in individuals diagnosed with NF1 [4]. Approximately 50% of NF1 cases are sporadic, involving de novo variants, while the remaining 50% are inherited [3]. More than 3,000 mutations have been reported in the NF1 gene, including single amino acid missense mutation, entire exon deletion, and mutations within intronic regions [5].

The NF1 gene encodes a neurofibromin protein, which acts as a tumor suppressor by regulating cell growth and proliferation [6]. Neurofibromin protein belongs to the family of negative regulators of the RAS proto-oncogene and GTPase-activating proteins (GAP)-RAS. This protein is expressed in cells of the nervous system, as well as in skeletal cells and tissues [7] . Exons 27-34 of the NF1 gene are responsible for encoding the GAP-RAS domain, which triggers RAS-GPT hydrolysis, leading to decreased RAS activity. In patients with NF1, mutations in the NF1 gene reduce GAP function, increasing RAS activity and promoting cell proliferation [8].

Currently, more than 2000 mutations in the NF1 gene have been identified and reported by the Human Gene Mutation Database. However, identifying these mutations is challenging due to the gene’s large size and the presence of pseudogenes. The phenotype-genotype correlation is complex; nevertheless, one of the clearest correlations is between large deletions, which occur in 4 to 11% of cases, and certain clinical characteristics such as cardiovascular involvement, tall stature with increased hand and foot size, and greater intellectual and skeletal compromise [9].

Conversely, specific mutations, particularly those involving stop codons or frameshift mutations, are associated with worse prognoses. For example, a 1.4 Mb deletion of the NF1 gene is associated with a more severe phenotype, including an increased number and severity of neurofibromas, as well as more severe cognitive abnormalities and an increased risk of developing malignancies [10]. Additionally, specific variants, such as p.Arg1809Ser/Cys/Pro/Leu and p.Met992del, can present typical pigmentary features even in the absence of obvious neurofibromas. This variability indicates that the same gene can produce a wide range of clinical phenotypes [11,12,13].

Although numerous NF1 variants have been reported worldwide, data on their molecular spectrum, genotype–phenotype correlations, and potential modifying factors in Latin American populations, particularly in Ecuador, remain scarce. Additionally, the role of genetic ancestry in influencing phenotypic variability in NF1 has not been systematically explored, despite its potential relevance for clinical interpretation.

Thus, the present study aims primarily to describe the clinical and molecular characteristics of three unrelated Ecuadorian pediatric patients with a presumptive diagnosis of NF1, confirmed by next generation sequencing. As a secondary objective, we analyze the genetic ancestry of each patient to investigate possible associations between ancestral background and phenotypic expression. By integrating clinical, molecular, and ancestry data, this study seeks to contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of NF1 in underrepresented populations, further supporting an earlier and more precise diagnosis.

Methods

Sampling and DNA extraction

The legal representatives of the three patients signed informed consent forms, and the patients provided their informed assent to participate in the study. The study was reviewed and approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of UTE University , approval code number CEISH-2021-014.

Peripheral blood samples were collected in EDTA tubes. DNA was extracted using the PureLink™ Genomic DNA Mini Kit, following the manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen). DNA quantity and purity were assessed by spectrophotometry and fluorometric quantification, and integrity was assessed via agarose gel electrophoresis.

Next generation s7equencing (NGS)

Genomic analyses were performed at the Centro de Investigación de Genética y Genómica (CIGG) of UTE University. The TruSight Cancer kit was used for sequencing DNA samples on a MiSeq platform, following the manufacturer’s instructions (Illumina). This panel covers 94 genes, and 284 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) (255 kb of cumulative target region size) that have been associated with common and rare cancers.

To identify potential variants and their association with the clinical diagnosis, data analysis was performed using Dragen Enrichment (v. 3.9.5). The workflow included: 1) alignment to the reference genome (hg38), 2) identification of genetic variants from the sequencing reads, 3) annotation of those variants with relevant information, and 4) filtering and prioritization of variants likely to cause the patient’s condition. The data generated were analyzed using the Variant Interpreter (Illumina) and Franklin (Genoox) platforms for variant annotation and classification. Both platforms were used in a complementary manner to enhance the accuracy and clinical relevance of the results. Notably, the Franklin platform applies the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology (ACMG/AMP) guidelines for standardized variant classification.

Ancestry analysis

A multiplex PCR reaction was performed to amplify 46 ancestry-informative markers (AIMs)-InDels, according to Zambrano, et al. (2019) [14]. Fragment separation and detection were executed on the 3500 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems). The results were collected on Data Collection v 3.3 and analyzed in Gene Mapper v. 5 (Applied Biosystems).

Results

The present study analyzed three cases of Ecuadorian patients with a presumptive diagnosis of NF1. Two of the patients were males and one female. Genomic analyses identified different variants in the NF1 gene.

Subject A

Subject A is a male child born in January 2021 in Sangolquí, Pichincha, Ecuador, with an ancestry composition of 86.6% Native American, 9.8% European, and 3.6% African, as determined by ancestry-informative marker analysis (Figure 1) [14]. At three months of age, clinical evaluation raised suspicion for NF1, based on the presence of multiple café-au-lait macules and craniofacial asymmetry. Ophthalmologic examination revealed thickening of the right upper eyelid, suggestive of an orbital plexiform neurofibroma (OPN). Additional findings included right-sided hemihypertrophy involving the tongue and palate.

Genetic ancestry composition of Ecuadorian subjects with (NF1).

Source: Prepared by the authors of this study.

The family history was notable for features potentially related to NF1. The patient’s brother had congenital lymphedema of the right foot and unilateral vision loss, likely secondary to keratoconus, but lacked café-au-lait macules or Lisch nodules. The patient’s mother and a maternal cousin both exhibited multiple café-au-lait macules, raising the possibility of familial NF1 (Figure 2).

Overview of NF1 in the three subjects.

Source: Prepared by the authors of this study.

At follow-up in October 2022, neurological examination documented additional café-au-lait macules (>5 mm in diameter), distributed as follows: right upper limb (n=4), left upper limb (n=1), right lower limb (n=5), left lower limb (n=4), anterior chest (n=3), and left axilla (n=1). Persistent right-sided proptosis was noted. Orbital magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a soft tissue mass adjacent to the right cavernous sinus, extending into the orbit. The lesion was in close proximity to the lateral aspect of the right optic nerve and adjacent to the lateral rectus muscle and orbital wall, reaching the ocular surface and eyelid. Associated findings included thickening of periorbital soft tissues, increased intraconal fat density, and right-sided exophthalmos. No bony erosions were observed, and the optic nerves were bilaterally preserved. These findings were consistent with an orbital plexiform neurofibroma.

Genetic testing via NGS identified a heterozygous nonsense variant in exon 35 of the NF1 gene, resulting in a premature stop codon (p.Arg1534Ter). This variant is classified as pathogenic (Table 1). The combination of clinical features and molecular findings confirms a definitive diagnosis of NF1 in this patient.

Subject B

Subject B is a 13-year-old male born in Quito, Pichincha, Ecuador, with an ancestry composition of 45.6% Native American, 41.8% European, and 12.6% African, as determined by ancestry-informative marker analysis (Figure 1) [14]. Since birth, he has exhibited multiple café-au-lait macules, and cutaneous neurofibromas began to emerge around the age of eight. A positive family history of NF1 was reported on the maternal side, with both his mother and maternal grandmother displaying clinical features consistent with the disorder (Figure 2).

During a genetic consultation in April 2023, physical examination revealed approximately 100 café-au-lait macules, axillary and inguinal freckling, and submammary cutaneous neurofibromas. Additional findings included limited extension of the elbows, a Galassi type I arachnoid cyst located in the posterior cranial fossa, and left-sided gynecomastia, which had been present since age ten. Hormonal evaluation at the time of gynecomastia onset revealed normal endocrine function.

Genetic testing via NGS identified a heterozygous missense variant in exon 1 of the NF1 gene, resulting in an amino acid substitution (p.Gln20His). This variant is classified as pathogenic and is consistent with the patient’s clinical phenotype (Table 1).

Subject C

Subject C is a 10-year-old female born in Saquisilí, Cotopaxi, Ecuador, with an ancestry composition of 67.1% Native American, 18.8% European, and 14.1% African, as determined by ancestry-informative marker analysis (Figure 1) [14]. At birth, she presented with more than 22 café-au-lait macules and bilateral axillary and inguinal freckling.

At age four, she underwent a bone graft procedure on her right forearm, which was repeated at age eight due to recurrence of the bone lesion at the same site. The initial injury was likely secondary to a post-traumatic fracture sustained from a fall at age two. On physical examination, the right forearm exhibited curvature and limited elbow mobility. Additional musculoskeletal findings included mild asymmetry of the knee folds, a tendency toward genu valgum, and a 5 mm length discrepancy favoring the right lower limb (thigh and leg) compared to the left.

Family history was notable for a maternal grandmother who died of colorectal cancer (Figure 2), although no direct NF1-related manifestations were reported in other family members.

Genetic analysis using NGS identified a heterozygous missense variant in exon 37 of the NF1 gene, resulting in an amino acid substitution (p.Asp1644Asn). This variant is classified as pathogenic (Table 1). The presence of this mutation, along with the patient’s cutaneous and skeletal manifestations, supports a clinical suspicion of NF1.

Discussion

NF1 is a rare autosomal dominant disorder caused by mutations in the NF1 gene, characterized by a broad spectrum of clinical manifestations including pigmentary abnormalities, tumor predisposition, learning disabilities, and skeletal defects [4,7]. Diagnosis can be particularly challenging in young children, as many diagnostic criteria emerge progressively with age. Moreover, NF1 is classified as a cancer predisposition syndrome, with increased risk for malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors, brain tumors, neuroendocrine tumors, breast cancer, and congenital cardiac anomalies [4,16,17]. Therefore, understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying specific phenotypes could facilitate the development of personalized therapeutic strategies aimed at improving quality of life in affected individuals.

In this study, we describe three unrelated Ecuadorian patients with clinical and molecular diagnoses of NF1. Each patient harbored a distinct pathogenic variant in the NF1 gene: Subject A carried a nonsense variant (p.Arg1534Ter), while Subjects B and C carried missense variants (p.Gln20His and p.Asp1644Asn, respectively). Loss-of-function mutations, including nonsense and deleterious missense variants, are the most common pathogenic alterations in NF1 [18,19].

Subject A exhibited a severe phenotype, including macrocephaly, multiple café-au-lait macules, and early-onset orbital plexiform neurofibroma, detected before six months of age, significantly earlier than the average age of diagnosis, which is typically around seven years. The p.Arg1534Ter variant lies within the RAS-GTPase-activating protein-related domain of neurofibromin [7,20], and the resulting premature stop codon likely disrupts neurofibromin function, contributing to the development of orbital plexiform neurofibroma and macrocephaly. Plexiform neurofibromas are reported in 30–56% of NF1 cases, but only 10% of infantile cases [21]. Orbital involvement, as seen in Subject A, is particularly concerning due to its risk of disfigurement and visual impairment. Notably, this variant has been previously reported in Chinese patients with orbital/periorbital plexiform neurofibromas [22], suggesting a possible genotype-phenotype association.

Subject A has been closely monitored with serial ophthalmologic and MRI evaluations. To date, the tumor has shown stable growth, with no evidence of optic pathway glioma or glaucoma. Interestingly, the same variant has also been associated with congenital pseudarthrosis of the tibia [23], although no skeletal abnormalities have been observed in this patient to date [24]. The presence of congenital lymphedema and unilateral vision loss in Subject A’s brother, despite the absence of a confirmed genetic diagnosis, further illustrates the phenotypic variability of NF1 within families [17,18].

Subject B carried a missense variant in exon 1 (p.Gln20His), classified as pathogenic. Mutations in this region, including p.Met1Val, have been associated with pigmentary features and cutaneous neurofibromas [20,25]. Subject B exhibited a classic NF1 phenotype, including extensive café-au-lait macules, axillary and inguinal freckling, and cutaneous neurofibromas. His mother displayed a similar phenotype, suggesting vertical transmission and cutaneous predominance of this variant. The p.Gln20His variant may destabilize neurofibromin’s structure, leading to its degradation via the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway [18]. This degradation could result in RAS-MAPK pathway hyperactivation, contributing to the observed phenotype.

Notably, Subject B also presented with unilateral gynecomastia, which on ultrasound appeared consistent with a subareolar neurofibroma. Although biopsy was declined, the lesion is being monitored clinically. Prepubertal gynecomastia associated with NF1 has been reported in the literature [26,27,28], and surgical excision has been successful in some cases. In our case, no surgical procedure was performed.

Subject C harbored a missense variant (p.Asp1644Asn) located within a conserved region of the neurofibromin protein that is critical for maintaining its structural stability and functional integrity [16,29]. The substitution of a negatively charged aspartic acid with a neutral asparagine at this position may disrupt local electrostatic interactions and hydrogen bonding networks [30], potentially impairing the ability of neurofibromin to regulate RAS signaling. This disruption could lead to prolonged RAS activation, resulting in uncontrolled cell proliferation and increased tumor susceptibility in individuals with NF1 [7].

The p.Asp1644Asn variant may prolong RAS activation, promoting continuous cell division, increased cellular proliferation, and reduced apoptosis. This mechanism likely contributes to the development of neurofibromas and other NF1-associated tumors [7,31]. Additionally, neurofibromin interacts with multiple signaling pathways involved in cell cycle regulation, cytoskeletal organization, and growth factor responses [32,33,34,35].

Moreover, in silico predictive tools support the pathogenicity of this variant: REVEL score of 0.86 (moderately deleterious), AlphaMissense score of 0.996 (strongly deleterious), and MetaLR score of 0.75 (deleterious). Furthermore, functional annotation of exon 37 reveals that this variant lies within an exonic hotspot, as evidenced by the presence of 19 pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants reported within a 106 bp region surrounding p.Asp1644Asn, with no benign missense variants identified in this segment. This clustering of deleterious variants further supports the functional importance of this region and the pathogenic nature of the p.Asp1644Asn substitution.

It is noteworthy that Subject C exhibited cutaneous manifestations, specifically café-au-lait macules and axillary/inguinal freckling, beginning in infancy. While these features are well-established diagnostic criteria for NF1, their presence from birth or early infancy is not frequently emphasized in the literature, where postnatal age ranges are typically used to describe their onset. This case reinforces the diagnostic value of pigmentary findings, particularly when both café-au-lait macules and freckling are present, even in very young children who may not yet meet other diagnostic criteria [36].

Over time, Subject C developed skeletal manifestations, including cortical thinning of the radial bone, which became evident following a post-traumatic fracture. The severity of the bone fragility required two surgical bone graft procedures. While tibial dysplasia is the most commonly reported osseous abnormality in NF1, this case highlights that radial involvement, though less frequent, can also occur and should be considered in the differential diagnosis of recurrent fractures in pediatric patients presenting with pigmentary signs [36].

This observation contributes to the growing body of evidence emphasizing the diverse clinical consequences of NF1 gene mutations, including pigmentary, skeletal, and tumor-related manifestations. These findings reflect the complex molecular and cellular functions of neurofibromin and help explain the wide variability in disease expression observed among individuals with NF1 [7].

Our results reinforce the diagnostic value of cutaneous features, particularly café-au-lait macules and axillary or inguinal freckling, as early indicators of NF1, even in infants who may not yet meet the full diagnostic criteria. In addition to these hallmark signs, we highlight less commonly reported manifestations such as radial bone dysplasia and prepubertal gynecomastia as relevant clinical features in pediatric NF1 [36].

Importantly, this case series also underscores the critical role of integrating genetic testing into the diagnostic workflow for infants and young children presenting with suggestive pigmentary findings, even in the absence of other classical features. Giugliano et al. (2019) demonstrated that molecular testing was instrumental in confirming diagnoses in individuals who presented solely with pigmentary features, specifically café-au-lait macules with or without freckling, in early childhood [36].

The prevalence of NF1 is estimated at 1 in 3,000 to 1 in 4,000 individuals [1,37], with significant variability in clinical presentation influenced by both genetic and environmental factors [38]. All three subjects in this study exhibited predominantly Native American ancestry, consistent with the genetic composition of the Ecuadorian population [14]. Although NF1 affects all ethnic groups equally, it is hypothesized that certain mutations may be enriched in specific populations and associated with distinct phenotypic patterns. Reduced genetic diversity in some populations may also facilitate the spread of specific variants, potentially influencing disease prevalence and expression [37,39]. Therefore, further studies exploring the ancestral context of NF1 may provide valuable insights into genotype-phenotype correlations and inform more effective diagnostic and therapeutic strategies.

This study has several limitations. First, the small sample size of three unrelated individuals limits generalizability to the broader Ecuadorian population. Second, while NGS identified pathogenic variants, functional studies were not performed to assess their biological impact. In particular, no transcriptomic or proteomic analyses were conducted, which, given the multifaceted role of neurofibromin in pathways such as RAS-MAPK, PI3K-AKT, and Mtor, could have provided deeper insight into compensatory mechanisms or dysregulated signaling pathways. Third, genetic testing was not conducted on all family members, restricting the ability to fully characterize inheritance patterns and potential genetic modifiers. Finally, short-term clinical follow-up, especially in pediatric patients, limits the detection of late-onset features such as plexiform neurofibromas, optic gliomas, or malignant transformation, underscoring the need for longitudinal studies to better understand genotype-phenotype correlations over time.

Conclusions

This case series illustrates the clinical and genetic heterogeneity of NF1 in a pediatric Ecuadorian cohort, emphasizing the importance of early recognition of cutaneous signs, particularly café-au-lait macules and freckling, as critical diagnostic indicators. The identification of three distinct pathogenic NF1 variants, including both nonsense and missense mutations, underscores the molecular diversity of the disease and its variable phenotypic expression, even among individuals with similar ancestry.

Notably, this study highlights less commonly reported manifestations such as radial bone dysplasia and prepubertal gynecomastia, expanding the clinical spectrum of NF1 in children. These findings reinforce the value of integrating molecular diagnostics into the clinical evaluation of NF1, particularly in young children who may not yet meet the full criteria. Future research should focus on elucidating genotype-phenotype correlations and exploring the role of ancestry in NF1 pathogenesis, with the ultimate goal of advancing personalized diagnostic and therapeutic strategies.