Research papers

← vista completaPublished on September 30, 2015 | http://doi.org/10.5867/medwave.2015.08.6271

Abdominal tuberculosis, a diagnostic dilemma: report of a series of cases

Tuberculosis abdominal, un dilema diagnóstico: reporte de una serie de casos

Abstract

INTRODUCTION Abdominal tuberculosis is one of the most common non-pulmonary tuberculosis infection sites, and it relates to immunosuppression. The nonspecific features of this form of tuberculosis make an accurate diagnosis difficult. The aim of this study is to report seven (7) patients diagnosed with abdominal tuberculosis requiring surgery at the Clinical Hospital of Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile.

METHODS A descriptive analysis of seven cases of abdominal tuberculosis treated in our center between August 2001 and June 2013 was performed to characterize its clinical presentation and diagnostic elements.

RESULTS Four men and three women (29-68 years old) were diagnosed and operated on for abdominal tuberculosis: three had the peritoneal form of tuberculosis, two had a lymph nodal form and two had the intestinal form. In three cases, abdominal tuberculosis was associated with immunosuppression (HIV and rheumatoid arthritis treatment) and six cases presented with wasting syndrome of at least one month duration. Three patients had an acute presentation with signs of intestinal obstruction. Diagnosis was made by surgical biopsy. Of the seven patients, who underwent surgery, three required bowel resection for intestinal obstruction.

CONCLUSION Abdominal tuberculosis requires a high index of suspicion for an early diagnosis, especially in populations at risk.

Introduction

In Chile, morbidity associated to tuberculosis (TB) has declined considerably in recent decades, from 52.2 per 100,000 habitants in 1989 to 18.4 per 100,000 in 2003. Mortality rate has dropped from 220.8 per 100,000 habitants in 1950 to 2 per 100, 000 habitants in 2002 [1].

Lungs are the most frequently affected organs in tuberculosis. Extra pulmonary disease is reported in 15-20% of cases and is proportionately more common in association with immunosuppression [2]. In HIV-infected patients, extra pulmonary disease can reach up to 50-70% [3],[4], with a higher proportion of atypical and disseminated forms, with cavitation and granuloma formation as a less frequent presentation.

The abdomen is the second most common site of extra pulmonary tuberculosis after the urinary tract [5]. Abdominal tuberculosis can occur as an isolated manifestation or in conjunction with pulmonary or lymph node infection. Active pulmonary tuberculosis foci have been reported in 15-20% of patients with abdominal tuberculosis [5]. In turn, 50-90% of patients with active pulmonary foci have some degree of gastrointestinal involvement, which is explained by the load of swallowed microorganisms [4],[5],[6].

Abdominal tuberculosis has an insidious course and nonspecific clinical manifestations, so its diagnosis is difficult [7],[8],[9],[10],[11],[12]. Etiologic diagnosis required histopathological and bacteriological analysis. Endoscopy and laparoscopy play a key role in taking samples for biopsy [4],[7],[13],[14],[15].

The aim of this study is to report a series of seven patients diagnosed with abdominal tuberculosis that underwent surgery at Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile Hospital.

Methods

Clinical records of patients who were admitted and underwent surgery for abdominal tuberculosis in the Service of Digestive Surgery at the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile Hospital between August 2001 and June 2013 were reviewed retrospectively.

Analysis of biopsies included histopathological features, histochemical study with Ziehl-Neelsen staining and molecular biology study of TB-632 with polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for the presence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in duplicate by amplification of sequences IS6110, with internal positive and negative external control.

Results

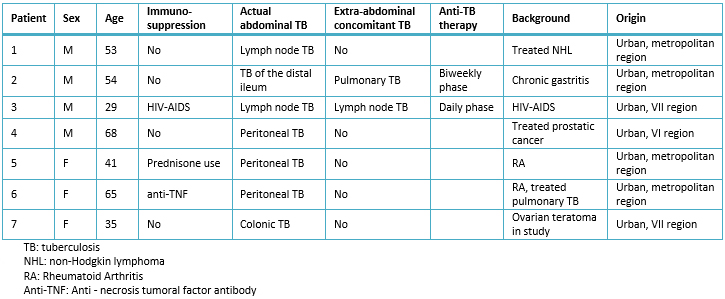

This series consists of seven patients who underwent surgery in our center with a postoperative diagnosis of abdominal tuberculosis. They were three women and four men. Age range was 29-58 years. Three patients presented with peritoneal tuberculosis; two patients had nodal affection and two patients had intestinal tuberculosis. Two patients had been treated for extra-abdominal tuberculosis when presenting abdominal symptoms (see Table 1). A patient without concomitant extra abdominal tuberculosis had history of treated pulmonary tuberculosis (medical management and pneumonectomy) 30 years ago. Only three patients had an immunosuppression condition (HIV or immunosuppressive therapy). Immunosuppressive therapy consisted in Prednisone or anti-TNF antibodies for the management of rheumatoid arthritis. One HIV-patient was on stage AIDS despite antiretroviral therapy and had been treated for concomitant extra-abdominal lymph node tuberculosis.

Table 1. Clinical data of patients who underwent surgery for abdominal tuberculosis.

Regarding clinical features, fatigue and weight loss were present in five patients. Those without this condition were in treatment with anti- tuberculosis drugs for concomitant tuberculosis. Abdominal pain was present in four of seven patients, three of whom had peritoneal irritation associated with fever. Patients without abdominal pain had an insidious clinical course: one patient presented with fever, night sweats and weight loss; another two patients presented with ascites and wasting syndrome. Abdominal symptoms were related to an acute complication of abdominal tuberculosis like intestinal perforation, cecal fistula, tuberculous peritonitis and intestinal obstruction.

All patients were studied with basic laboratory tests, with nonspecific results. This initial study guided management in patients with a severe underlying complication. All patients were studied with contrasted computed tomography that suggested diagnosis of tuberculosis in four cases. These signs suggestive of tuberculosis included intestinal parietal thickening in three cases and retroperitoneal lymph nodes and cecal fistula in one patient. Colonoscopy was performed in three cases; one patient had suggestive features (sores and ulcers), but the pathology showed nonspecific colitis.

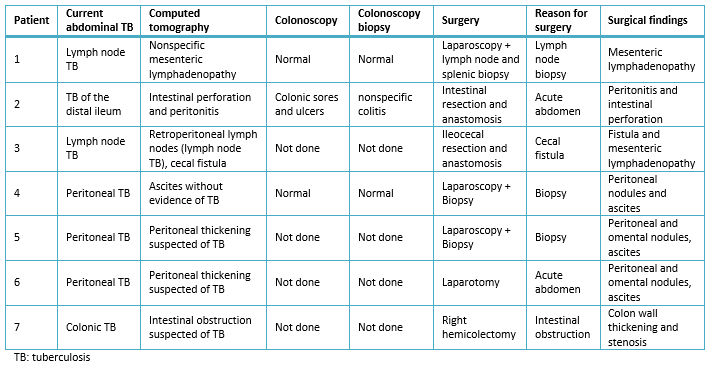

Seven patients underwent surgery to obtain samples for pathological examination. The details of the interventions performed are presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Clinical findings in patients who underwent surgery for abdominal TB.

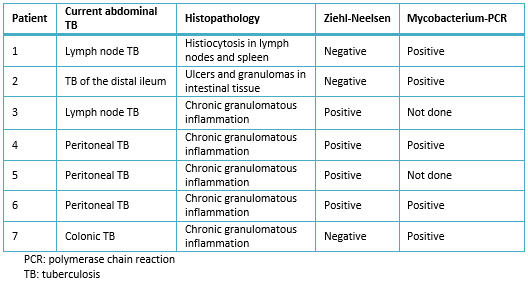

Intraoperative findings were peritoneal nodes, omental implants, ascites in peritoneal tuberculosis cases; intestinal parietal thickening in cases of intestinal tuberculosis and lymph nodes in lymph node tuberculosis. The summary of the pathologic findings is presented in Table 3.

Table 3. Histopathological findings in patients who underwent surgery for abdominal TB.

Discussion

Abdominal tuberculosis represents a diagnostic challenge. It requires a high suspicion index to make an accurate diagnosis by performing a sequential and standardized study. Several diagnostic elements are common with other abdominal diseases, but these should be key to suspect abdominal tuberculosis [3],[9],[14].

The risk population is mainly immunocompromised subjects: HIV (+), people with immunosuppressive therapy and cachectic states. Immunosuppression must be considered an element of suspicion of TB in all its forms, but this context should suggest atypical presentations of tuberculosis [5],[6],[16],[17]. In our study, almost half of the cases were associated with immunosuppression; most of them had a consumptive disease with an acute event that triggered consultation.

Laboratory and imaging tests are key to assess primary evaluation, detect possible complications, rule out other diseases and guide further tests. Higher resolution images, such as computed tomography can demonstrate findings suggestive of tuberculosis and guide appropriate histopathological study to confirm the diagnosis [1],[3],[4]. In our series, computed tomography showed findings suggestive of abdominal tuberculosis in four patients.

There are endoscopic abnormalities suggestive of tuberculous enteritis, which can confirm the diagnosis through the histological study in a number of cases; in other cases [4],[13],[15],[18], it will be difficult to distinguish from other causes of chronic intestinal inflammation such as Crohn's disease [19],[20],[21],[22]. In our experience, although colonoscopy was not performed in all cases, when performed, it provided therapeutic guidance.

The etiological confirmation must consider usual microbiological analysis and molecular analysis if histological study is inconclusive [4],[6],[18]. In our series, PCR for Mycobacterium was necessary to confirm the diagnosis in 5 patients. In 2 cases the diagnosis was made solely on the basis of molecular analysis.

There is a group of patients, who despite all of the above, can still not achieve confirmation of tuberculosis. A very high clinical suspicion even without histological confirmation allows starting a course of medical treatment and assesses clinical response ("therapeutic trial") [1],[23],[24]. Therapeutic trial required an appropriate clinical follow-up. Laboratory parameters and endoscopic studies play an important role in this assessment [5],[6]. In our series, surgical exploration was an adequate way to obtain samples for histopathological and molecular analysis. This study confirmed diagnosis of tuberculosis.

Conclusion

Abdominal tuberculosis requires high index of suspicion for early diagnosis, particularly in populations at risk. Clinical context, associated with an insidious, progressive and consumptive course is a characteristic setting of tuberculosis [24],[25]. Computed tomography and adequate biopsy sampling are key for diagnostic confirmation.

Notes

From the editor

This article was originally submitted in Spanish and was translated into English by the authors. The Journal has not copyedited this version.

Ethical aspects

The Journal ethical aspects editor reviewed the original manuscript of this article. He considers that, since the cases were analyzed retrospectively from clinical records, the identities of the patients are not discernible nor traceable from the information provided in the article. This protects the confidentiality of sensitive data of the patients, who do not suffer any physical or psychological intervention as part of the study. Consequently, no violation of basic principles of research ethics are violated.

Conflicts of Interests

The authors completed the conflict of interests declaration form from the ICMJE, and declare not having any conflict of interests with the matter dealt herein. Forms can be requested to the responsible author or the editorial direction of the Journal.