Research papers

← vista completaPublished on July 22, 2016 | http://doi.org/10.5867/medwave.2016.06.6501

The Cuban Institute of Oncology and Radiobiology experience on the beliefs and opinions about digital rectal exam in urological patients

Creencias y opiniones sobre el examen dígito rectal en pacientes urológicos: experiencia en el Instituto de Oncología y Radiobiología (Cuba)

Abstract

OBJECTIVE To describe the beliefs, knowledge and opinions that influence the practice of digital rectal examination in a group of urological patients.

METHODOLOGY A descriptive study was conducted using convenience sampling and an anonymous questionnaire with 15 questions. The questionnaire was divided in three blocks: socio-demographic variables; delay in going to the urology clinic and taking the rectal examination; evaluation of patients’ perception of pain and discomfort during digital rectal examination and the impact of discomfort on potential future screening compliance. Percentages were used for the descriptive analysis.

RESULTS Eighty-five surveys were conducted at the Institute of Oncology and Radiobiology of Cuba. The results showed that 70.24% of participants to some extent had information about prostate cancer and 64.29% about prostate specific antigen. Only 27% thought that the digital rectal examination would be helpful, while 66.66% delayed their visit to the urologist in order to avoid the digital rectal examination and 79.76%, to elude the biopsy. It was observed that 52.39% and 36.90% of men complained of moderate and severe pain, respectively. Digital rectal examination was deemed traumatic by 61.9% of the surveyed men. A high number of patients responded they would repeat prostate exam the following year (88.09%) and 94.05% would encourage a friend to have the prostate exam.

CONCLUSIONS More than half of the sample claimed to know about prostate cancer and prostate specific antigen; however, they did not consider helpful to undergo digital rectal examination. The main reasons for not assisting to the urologist was to avoid biopsy and the digital rectal examination. Nonetheless, in most patients traumatic digital rectal examination was performed and responders said they would repeat it in the future.

Introduction

Prostate cancer is a world health problem as it is the second tumor diagnosed in men worldwide, with 1.1 million new cases annually. The appearance of this type of tumor is increasing due to the growth and aging of the population. The variation in incidence rates is the reflection of the widespread use of prostate specific antigen (PSA) testing, its tumor marker par excellence [1].

According to data published in GLOBOCAN, prostate cancer is the fifth leading cause of cancer death throughout the world. The highest mortality rates were observed in the Caribbean and in South Africa [2]. The five-year prevalence of this disease for Latin America and the Caribbean is 40% [1]. In Cuba, according to the Health Statistical Yearbook 2014, this type of tumor is the second in incidence and second in mortality. The clinical stages distribution of the cases studied shows an increase in diagnosis in advanced stages, with an incidence of 3,023 cases and an age-adjusted rate of 33.3 per 100 000 inhabitants. The total number of cancer deaths in the Cuban population was 2,793 cases in 2014, with 50.1 crude rate per 100 000 inhabitants [3].

Before the introduction of prostate specific antigen, prostate cancer was diagnosed in individuals with clinical symptoms (indicative of advanced disease) and older than 70 years. Currently, about 60% of newly diagnosed cases are men over 60 years. Localized disease (detected in asymptomatic individuals) represents about 82% of all cases and leads to a relative five-year survival of 100% [4].

The combined use of digital rectal examination (DRE) and prostate-specific antigen, is the method used in secondary prevention with periodic screening in men over 50 years with a more than 10 years life expectancy and after discussion with the doctor about the risks and benefits of their practice [5],[6],[7],[8]. Yet, there are several controversies concerning to prostate cancer screening [9],[10].

The factors that influence the adoption of healthy and preventive behaviors, such as screening, may be multiple because they not only depend on its implementation by the Ministry of Public Health of Cuba. People make decisions about preventive practices according to their perceptions and assessments, made individually or in groups, on the consequences of such practices. Taking into account all these factors, the present study was developed in order to describe the beliefs, knowledge and opinions about the digital rectal exam in a group of urological patients who attended to the Institute of Oncology and Radiobiology of Cuba.

Methods

A cross-sectional descriptive study was conducted based on self-perception interview about prostate cancer and its diagnostic methods. It was carried out from May 2015 to February 2016, at the Institute of Oncology and Radiobiology (INOR), in patients who came to the urologist consultation for the first time. This research was performed according to the protocol approved by the Scientific Council and the Ethics Committee of the INOR, following the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, with the current review of 2013 [11].

Universe and sample

The universe consisted of all patients who attended the urologist consultation at the Institute of Oncology and Radiobiology, for a review or because of urinary obstructive symptoms. Participants were a convenience sample and the interview was conducted by pollsters trained in the clinical area. They invited to participate individually, men between 45 and 70 years old, to whom the aims of study were explained and presented and who were given a preliminary talk on what the study was for. Data concerning socio-demographic variables were collected anonymously and it was verified that they had no physical or mental conditions preventing their participation. The latter, along with the age outside the range described above, were the exclusion criteria.

Informed consent was requested from each participant before he answered the questionnaire. The urologist and a resident in oncology were always present in each interview. In most cases (78%) one family member (wife or daughter) was also present. After the completion of the questionnaire, a pamphlet with information about the disease was given to each participant, so they could be able to review and check their answers to pollsters, as required [12].

The principal investigator reviewed each questionnaire and verified its proper implementation. To confirm the data accuracy, 10% of participants were randomly selected for a new interview by phone. To avoid bias, each interview was coded and was analyzed by the principal investigator who did not apply the survey instrument.

Questionnaire design

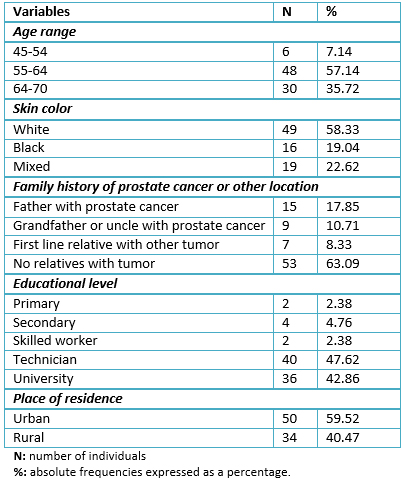

In the absence of validated questionnaires on the subject at the Institute of Oncology and Radiobiology, the present one was built starting with 15 questions grouped into three blocks, with application time estimated to be 30 to 35 minutes. The interview blocks 1 and 2 lasted 10 to 15 minutes, pollsters waited five minutes after digital rectal examination and then resumed for 10 minutes to perform questions of block 3. For each question data were organized, coded and categorized. Frequencies and/or percentages by subject category were also calculated. The first block contained socio-demographic variables (Table 1): age, skin color, educational level, place of residence (rural or urban) and family history of prostate cancer or other locations.

Table 1: Socio-demographic and clinical variables of sample individuals at National Institute of Oncology and Radiobiology, Cuba.

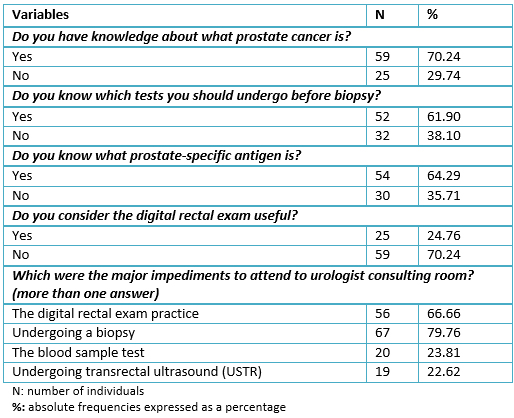

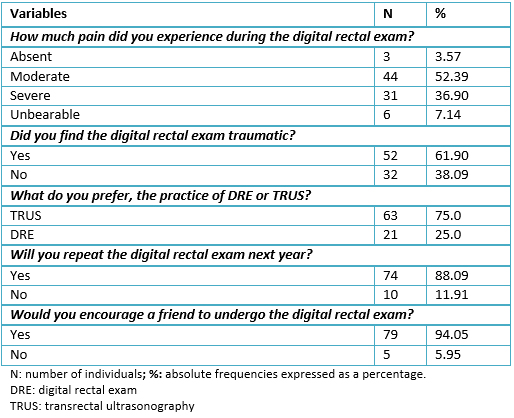

For age analysis purposes participants were split into three groups: 45 to 54, 55 to 64 and 65 to 70 years. Meanwhile, for schooling they were classified into four major ranges according to educational levels acquired by a person in Cuba: primary, secondary, skilled worker, technician, university. The second questionnaire block (Table 2), focused on the type and way of getting information about prostate cancer and digital rectal examination. This block, was also linked to the reluctance to go to the urology consulting room and intend to practice rectal examination. The third block of the questionnaire (Table 3), directed the questions to nonconformity with digital rectal examination once it was practiced and to the possibility of a medical exam periodically. In order to perform the digital rectal examination to each patient, the urologist took him to a contiguous and private room. Before executing the procedure, the urologist explained everything about the digital rectal exam. Prior to the procedure, lidocaine topical gel at 2% was applied, the position adopted for the digital rectal exam was lateral decubitus.

Table 2: Questionnaire results of individuals at National Institute of Oncology and Radiobiology, before digital rectal exam practice

Table 3: Questionnaire results of sample individuals at INOR, applied after digital rectal exam practice.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics to summarize categorical variables were absolute frequencies and percentages. We created a database in Access program and used the statistical program GraphPad Prism 5.0. The beliefs held by individuals on testing for prostate biopsy, the degree of nonconformity with the digital rectal exam and the possibility of a periodic medical examination, were expressed as dichotomous variables (yes or no). The major impediment to attend the urologist consultation (undergo prostate-specific antigen testing, digital rectal examination, biopsy or ultrasound), and the level of painful examination (absent or low versus moderate, severe or unbearable) were categorical variables. The results were presented in a workshop at the Institute of Oncology and Radiobiology, where the participants in the study and population were also invited. All of them received information and training on the topic in two scheduled sessions, taking into account the research findings.

Results

Data from 95 questionnaires were processed, however, once quality control was performed before digitation; eleven were canceled (seven for absence of some answers and four for inconsistencies), finally a total of 84 surveys were analyzed. Median age was 66.24 years (range 49-70). Patients with ages between 55 and 64 years old were more frequent (Table 1). Individuals with white skin color and no family history of prostate cancer, predominated. In addition, it was perceived that most patients attending the urology consulting room had an average or higher level education, and were mostly from urban and not rural areas (Table 1).

Over 50% of patients stated to have knowledge about prostate cancer and its diagnostic tools (Table 2). However, 70.24% of individuals revealed their discomfort with a digital rectal exam and considered it ineffective. The major impediments to attend to the urologist consulting room were not undergoing a biopsy (79.76%), or evade the digital rectal exam practice (66.66%).

The degree of discomfort associated with pain was summarized in Table 3 where 52.39% and 36.90% of patients reported moderate to severe pain during the digital rectal exam, respectively. This led to the 61.9% of individuals that found traumatic the digital rectal exam. However, there was a propensity to undergo the transrectal ultrasound (75.0%), with more consent. Eighty eight percent of subjects responded that they would repeat the digital rectal exam next year and also would invite a friend to a similar medical exam.

Discussion

More than two decades ago it was accepted as a general consensus, that a biopsy should be indicated only when the digital rectal exam was suspicious and/or the prostate specific antigen levels were higher than 10 ng/ml. However, since the publication of the multicenter study carried on by Catalona et al. [13], in 18% of men in whom a prostate biopsy was performed, it was necessary to change this idea. Because prostate cancer was found in 21% of cases with prostate-specific antigen values range 4 to 10 ng/ml with no indication of malignancy on digital rectal exam. This percentage was similar to that found in included cases with suspicious digital rectal exam (21%).

Digital rectal exam is an important clinical tool used on individuals, with the aim of providing information about the morphology, size, consistency, mobility, shape, sensitivity and presence of nodules on the prostate gland, so it is of great clinical utility for diagnosis. The combined effect of the digital rectal exam test with the values of prostate specific antigen, facilitates the early detection of prostate cancer [14],[15], even though the use of mass screening continues controversial [9],[10],[16].

In spite of a large number of prostate cancer deaths in Cuba, men are not familiar with the digital rectal exam practice. This has a negative influence on mortality, as there are a high number of patients diagnosed in advanced stages [3]. In addition, we did not count on validated questionnaires to assess knowledge about prostate cancer or about criteria, beliefs and factors that might influence the performance of the digital rectal examination, in Cuban individuals.

In order to eliminate barriers to access to this preventive and free service of the Ministry of Public Health of Cuba, the development of actions is necessary to ensure a higher quality induction demand on digital rectal examination practice, as the most appropriate and relevant information concerning the practice of this test as was described in this study, according to the points made by other authors [12],[17]. To generalize this study, the potential offered by primary care in Cuba will be used. The Cuban family doctors systematically perform digital rectal examination to a high number of patients older than 50 years, who present symptoms of obstructive lower urinary tract and frequently, measures of prostate specific antigen are made.

The present study found a large number of patients with affirmative answer about prostate cancer knowledge and prostate-specific antigen, these results were higher than those reported by other authors in Latin American countries who developed similar studies [18],[19],[21]. This fact suggests that the elevated educational standard and literacy existing in Cuba, could have had a positive impact on the information levels about prostate cancer and its diagnostic methods. Regarding this aspect, it has been raised in similar studies that psychosocial and demographic factors along with beliefs, were the biggest obstacles to perform the digital rectal exam and prostate cancer screening enrollment [22],[23],[24].

One of the biggest fears persisting in Latin American men is undergoing the prostate test, even though this can save their life. This palpation produces a lot of insecurity for fear of losing masculinity. This concept, which has the man about himself and is related to a culture and custom rooted in most Latin American countries [18],[19],[20],[21], is not restricted only to Latinos, African Americans suffer from similar insecurities [24],[25]. In consideration of the foregoing, it has been suggested that some socio-demographic factors such as beliefs, anxiety and attitude to a rectal examination [18],[19],[21],[24], may adversely affect the test. This generates a delay in the visit to the urology clinic, which could be related or not with the diagnosis delay of the disease.

Similarly, the reluctance of men to admit weakness or decay, or feel that their capacity is reduced due to a disease, could lead not to look timely for health care, setting up a phenomenon that has been called "marginalized masculinity " [26].

The level of discomfort given by the degree of the referred pain to the digital rectal exam, was postulated as one of the main barriers to conducting screening in the population [27],[28]. Over 50% of patients explored in the present study felt pain and were uncomfortable performing the test. About this, it is known that the pain may be due to the contraction of the sphincter and palpation of the prostate, seminal vesicles and bladder trigone. These structures are innervated by the visceral nervous system, which transmits pain sensation through the parasympathetic and sympathetic autonomous nervous system [27]. This high pain perception observed in the present study, was also reported by other authors [18],[19],[21]. Besides, the discomfort of the exam or preventive action (here takes relevance shame and the possibility of a threat to their privacy during the prostate exam) was also the subject of others studies [29],[30] where results were similar to ours.

Rejection of the biopsy and the digital rectal examination, caused reluctance to go to the urologist consultation in most of the interviewed individuals. This type of behavior may affect early detection disease, as has been proposed by other authors [19].

In spite of the above, 88.09% of respondents agreed to undergo the digital rectal exam procedure again and 94.5% would encourage a friend. This indicates that, despite of taboos concerning the realization of digital rectal examination, this would not influence the performance of future research. These results were consistent with other investigations with similar purpose than the present study [21],[22],[27].

The limitations of this study have to do with its not probabilistic sample, which prevents inferences or causality conclusions. An additional limitation was related to the fact that information about the practice of digital rectal exam was self-reported. This is a bias found in the study results, given the tendency of individuals to give answers which might satisfy the pollster, especially if it is a female, as it was the case in this study. Taking this into account, the practice antecedent of digital rectal exam can be even lower than described. In addition, the design was structured and predetermined, which limited the collection of more comprehensive data.

Despite limitations referred to, the study results are useful to guide actions in order to increase the coverage of the digital rectal exam practice. Although the intention is to have an approach to future behavior, it may be affected by multiple factors that reduce its prediction. For this reason, subsequent cohort studies where individuals are followed may help to establish the correlation between intention and practice of digital rectal examination.

The main strength of this study was that its development led to the creation of the questionnaire. It was made and implemented for the first time following a rigorous process at the Institute of Oncology and Radiobiology, of Cuba.

In order to eliminate access barriers to this preventive service, the Cuban Ministry of Public Health will need to develop the necessary actions to ensure higher quality in inducing demand of the digital rectal exam, as well as providing more appropriate and relevant information to a higher number of men. Additionally, it will improve services on prevention and early detection of prostate cancer, not only limited to the scope of health professionals, but also to the general population for awareness in prevention and early detection of prostate cancer; given this pathology constitutes the second cause of death in Cuban men [3].

Thus, future studies on a large scale, should further extend the issues raised in this descriptive study. The results should help to structure actions that improve the opportunity of access to other diagnostic variants such as transrectal ultrasound, contributing to increased specificity of the prostate biopsy. Similarly, the study will allow to increase and improve the information about prostate cancer and digital rectal exam practice for Cuban men.

Conclusions

More than half of the sample of individuals studied, claimed to know about prostate cancer and prostate-specific antigen. However, they did not consider profitable to undergo a digital rectal exam. Furthermore, avoiding to undergo a biopsy or a digital rectal examination were the main impediments to assist to the urologist consultation room. Although in most patients the digital rectal exam was traumatic, they agreed to repeat it in the future.

Notes

From the editor

The authors originally submitted this article in Spanish and was translated into English by the authors. The Journal has not copyedited the English version.

Ethical aspects

The Journal is aware that all participants signed the informed consent form and that the Research Ethics Committee of the Institute of Oncology and Radiobiology in Havana, was informed about this study and its possible publication in a journal of biomedical diffusion.

Conflicts of interest

The authors completed the ICMJE conflict of interest declaration form, translated to Spanish by Medwave, and declare not having received funding for the preparation of this report, not having any financial relationships with organizations that could have interests in the published article in the last three years, and not having other relations or activities that might influence the article´s content. Forms can be requested to the responsible author or the editorial direction of the Journal.

Funding

The authors declare that there was no funding coming from external sources.