Research papers

← vista completaPublished on May 23, 2019 | http://doi.org/10.5867/medwave.2019.04.7637

Health determinants in adults in Chimbote, Peru: A descriptive study

Determinantes de la salud en adultos de la ciudad de Chimbote, Perú: estudio descriptivo

Abstract

Objetive To describe health determinants in adults from the jurisdictions of the North and South Pacific Health Networks in the city of Chimbote.

Methods A non-controlled descriptive study was carried out. Health determinants were classified in the following categories: bio-socioeconomic characteristics, lifestyle, and social and community support. For the descriptive analysis of categorical variables, relative and absolute frequencies were used.

Results A total of 1 496 adults were included in the study. In the bio-socioeconomic determinants category, 62.2% were women and 53.3% were older adults. In the lifestyle determinants category, 52.4% did not smoke and had not ever smoked regularly, 50.5% did not consume alcoholic bever-ages, and 66.9% had 6 to 8 hours of sleep. In the social/community support determinants category, 53% had been treated at a health facility in the previous 12 months, 47.5% considered the distance between the health facility where they were treated and their home to be average, and 64.6% had public health insurance (SIS) from Peru’s Ministry of Health (MINSA).

Conclusion Most participants completed high school but this level of education did not result in access to higher-scale salaries. In addition, most partici-pants owned their own homes as well as access to basic services but lived in overcrowded conditions. A sedentary lifestyle and high-carbohydrate diet were predominant in this sample, highlighting the need for education to improve health.

|

Key ideas

|

Introduction

Health is a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being[1]. An individual’s health is affected by contextual conditions that, for the purpose of this research, include a set of social, economic, political and lifestyle factors that are established in the human life course, translate into future health impacts[2], and are therefore known collectively as determinants of health.

Considering all ages, the global population increased by 1.2%, to 7 530 million people, between 2000 and 2017. Of these, 65% are between 18 and 64 years old[3]. Over time people often adopt unhealthy lifestyles or behaviors (e.g., smoking, alcohol abuse, poor eating habits)[4],[5],[6] that, with various social and economic conditions (poverty, type of residence, gender issues, and education level, among others) can affect the occurrence and co-occurrence of communicable and noncommunicable diseases in adulthood[7],[8],[9].

Despite advances in the diagnosis and treatment of diseases, the social determinants of health have not changed, although they have become mo re complex[10]. Because of the unsatisfactory health status of populations worldwide, health systems have strengthened comprehensive primary health care, shifting attention and priorities to health promotion and disease prevention[2],[11]. The objective of this study was to describe determinants of health in adults from the jurisdictions of the North and South Pacific Health Networks in the city of Chimbote, Peru.

Methods

Design and context of the study

This was a descriptive study with a single-box design[9]. The research was conducted in the city of Chimbote. The Chimbote health system is under the jurisdiction of the North Pacific Health Network and the South Pacific Health Network. Each of the two networks includes six micro-networks. Four of the 12 micro-networks—three from the North Pacific Health Network (El Progreso, Magdalena Nueva, and Miraflores) and one from the South Pacific Health Network (Yugoslavia)—are in the city of Chimbote. All four micro-networks participated in the study. The sampling frame consisted of adults (≥ 18 years old) from the four micro-networks. A probability sample of 1 496 adults was obtained using simple random sampling.

Participants

Men and women 18 years or older who were treated in the selected health networks were considered eligible. People with mental disorders who were unable to complete the study procedures were excluded.

Ethical aspects

Permission from the North and South Pacific Health Networks was obtained before carrying out the study. Subsequently, the lead researcher obtained informed consent from each selected participant prior to applying the assessment instrument. The study was carried out between April and September 2016. No participant surveys were excluded from the study.

Instruments

The Social Determinants of Health questionnaire was adapted for Peru and validated by ten experts[12]. Based on a statistical test, the instrument showed high reliability (Cronbach’s α = 0.89). The questionnaire included 30 items divided into four parts:

- Identification data.

- Bio-socioeconomic determinants: sex; age (young adult, 18–29 years; middle-aged adult, 30–59 years; and older adult, 60 to more years)[12]; education level; economic income; occupation of head of household; housing type, tenure (financial arrangements), and material; number of people in the household, and number sharing a bedroom; basic services received at the home, excreta elimination, and garbage disposal.

- Lifestyle determinants: tobacco consumption, alcohol consumption, hours of sleep, frequency of personal hygiene, use of health services, physical activity, and food consumption;

- Social/community network determinants: support from friends/family, social services support, wait time and quality of support services, and exposure to gangs.

Dependent variable: determinants of health

Determinants of health are a “set of personal, social, economic, and environmental factors that determine the health status of the person”[2]. In this study, we describe “determinants of health” using the categories described above (bio-socioeconomic, lifestyle, and social/community support). The same categories and their subcategories were used in the analysis.

Data analysis

For the analysis, a database was created in Microsoft Excel 2016 and exported to the statistic software IBM SPSS Statistics 24.0 for data processing. For the descriptive analysis of categorical variables, absolute and relative frequencies were used.

Ethical considerations

The confidentiality described in the consent form of the original study was respected through the anonymization of the data, its restricted handling, and encrypted registration. The study was reviewed by the Institutional Research Ethics Committee of the Universidad Católica Los Ángeles de Chimbote (CIEI-ULADECH Católica), which issued authorization reports (#006-2016-CEI-VI-ULADECH-Católica) prior to its execution.

Results

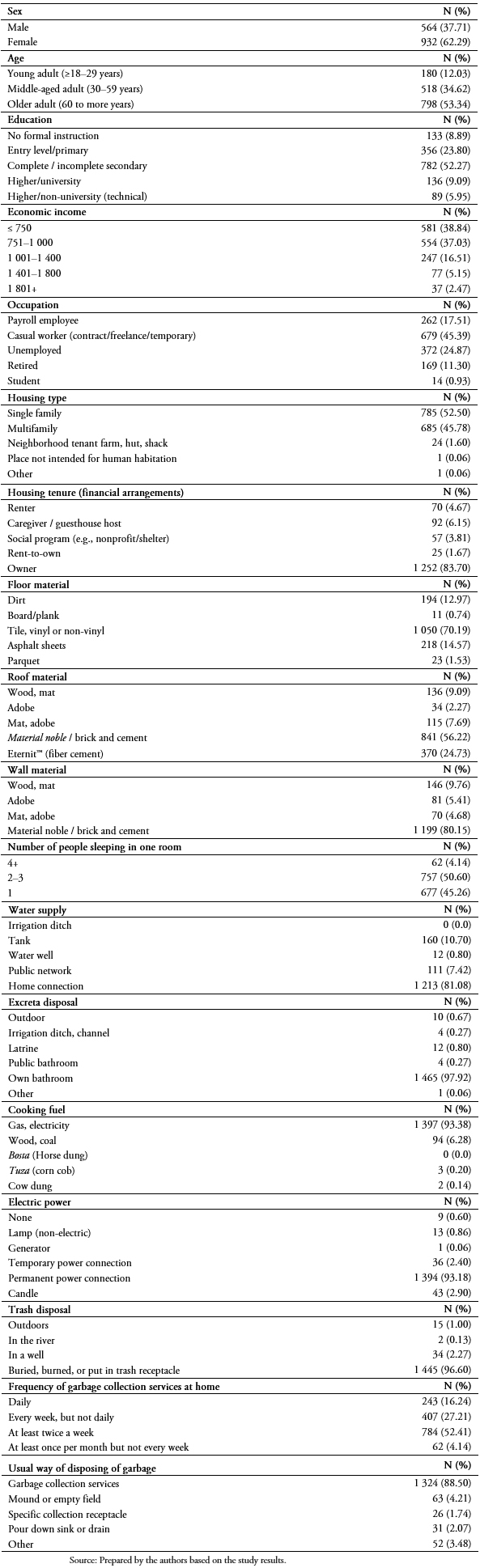

Results for bio-socioeconomic determinants included the following: 62.2% of the participants were women; 53.3% were older adults; 52.2% had complete/incomplete secondary education, and 38.8% had an economic income less than 750 Peruvian soles (Table 1).

Full size

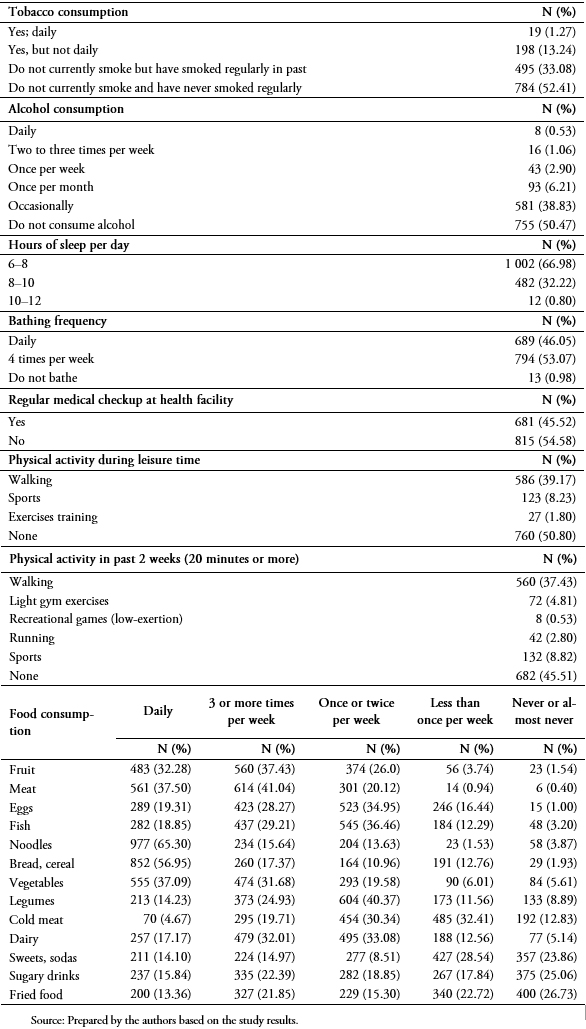

Full size For lifestyle determinants, 50.5% did not consume alcoholic beverages; 66.9% sleep 6–8 hours; and 54.4% did not receive regular medical checkups. With regard to diet, 27.4% consumed fruit three or more times per week, and 28.5% consumed sweets/sodas less than once a week (Table 2).

Full size

Full size For determinants related to social/community support, 53% had been seen at a health post in the last 12 months; 64.6% had the Ministry of Health (MINSA) Comprehensive Health Insurance (SIS); 52.5% indicated gangs or crime near their home; and 96.9% said they did not receive any formal/organized social support (Table 3).

Discussion

The increase in life expectancy along with the decrease in the birth rate implies aging of the population and, with it, new problems for a modern and changing society where older adults are low on the scale of social recognition. Herein lies the importance of analyzing the bio-socio-cultural, dietary, and social conditions in which this population group develops[6],[13].

In the category of bio-socioeconomic determinants, we found that more than half of the respondents were older adults, the majority were female, and more than half had complete or incomplete secondary education. These results were similar to what was found in a study conducted in Trujillo, Peru[14] (other than the proportion of age groups, as the latter sample was composed entirely of middle-aged adults). Similar results were also found in a study by Quiroz R in which more than half of the participants were women, 41% had complete/incomplete secondary education, and 75.8% were young adults[15]. Another study of social determinants of health carried out in Colombia found that 48.9% of the study population were middle-aged (41–64 years old), more than half (61.4%) were female, and 35.2% had studied at the undergraduate or postgraduate level[16]. Our results and those of the previously described studies show a relationship between age and education gaps, and the education gaps influence income, which in turn affects individuals’ general quality of life[17].

The majority of participants in this study reported their income as below Peruvian minimum wage (750 soles per month), and most of them said they had casual jobs. This is consistent with what was reported by residents of Piura[18], who said their income was below the minimum wage, and that 74.9% of them had casual jobs, with only 0.9% unemployed, but salaries were below the minimum wage. Different results emerged in the study in Colombia, in which 88.9% of study participants had high socioeconomic status, and 37.3% reported a salary of more than six times the minimum wage Colombian, but 30% said they were unemployed at the time of the survey[16]. Disparities in the type of available jobs, as well as the remuneration, seem to be based on age and academic degrees, with people who have not achieved a certain level of education forced to accept poor working conditions with salaries below the minimum wage. These disparities can also affect health, as shown in studies where people with higher incomes had better self-care[19].

Most of the study participants said they lived in single-family homes, but a little more than half said more than three members of the family shared a room. This is similar to the results of the studies in Piura[18] and Colombia[16]. The large proportion of home ownership could be due to the lower cost of land during certain periods, or to the land invasions (squatter settlements) that eventually led to access to property titles when many houses were built without professional guidance/standards. The increase in the number of family members living in the same house was not anticipated and led to overcrowding in areas with limited space[20],[21].

More than half of the study participants said they received their water supply through household connections, and most said they had their bathroom. Fuel for cooking was either gas or electricity, most houses had a permanent power connection, and almost all participants said they had garbage collection services for trash disposal. This is similar to what was reported in the study in Piura[17], and in a study in a rural community in Colombia[22], where 97% had electricity and more than half (58.6%) had garbage collection services, but most (69%) lacked access to safe drinking water, and only 20.7% have sewer services. Improvements in the level of basic service provision in some countries are due to social policies developed in recent years to reduce poverty and improve quality of life and social development. However, political will and commitment of government authorities are still needed to address gaps related to these important social determinants of health[23].

In the category of lifestyle determinants, a little more than half of the respondents reported not smoking and not drinking alcoholic beverages, and most said they usually sleep 6–8 hours. More than half said they did not receive regular medical checkups, and about half said they do not go for a walk in their spare time. Similar data were reported in the study by Navarro[18] in Piura. Of that study sample, 49.8% said they consumed alcoholic beverages occasionally, while 79.6% expressed concern about access to regular medical checkups at a health facility. Another study in Peru showed that 93.7% of residents in urban and semi-urban areas were not physically active[24], and a study in rural China reported that more than half of the respondents (86.2%) abstained from alcohol consumption but only a quarter (25.5%) did any outdoor physical activity[25]. A more proactive lifestyle in which physical exercise is done regularly, with a better quality of sleep, would improve peoples’ perception of their health[26].

With regard to food intake, almost all participants in our study said they consumed noodles, bread, and cereal daily and about half said they ate meat three or more times per week; only a quarter said they did not consume any fried foods. In the Piura study[18], more than half (66.8%) reported daily consumption of fruit, 38.4% said they consumed fish three or more times per week, and 57% said they consumed sweets/sodas less than once per week. The study carried out in Trujillo[14] found that the majority of participants (99%) consumed fruits and vegetables three times a week. A healthy diet is a known determinant for good health[26].

In the category for social/community support, more than half of the respondents said they had been seen at a primary-level health post in the last 12 months. These results differ from what was reported by Navarro[18]and Flores[14], which showed the majority of respondents had received treatment at a health facility in the last year. The results of our study suggest that at least some of the participants want to receive regular medical checkups, as well as knowledge about activities conducive to good health. A little less than half of our study participants reported a average distance between their homes and a health facility, which was similar to the results of the Flores study[14], but different than those for the Navarro study[18], which found that medical treatment was accessible very close to home for most participants (78%). Proximity to a health facility is a health advantage, especially in an emergency, but also for regular care and prevention, which many participants in our study said they would appreciate.

For health insurance, most participants in this study had SIS, the comprehensive health insurance provided by MINSA. This finding is similar to what was reported by Flores[14] and Navarro[18]. The current policies of the Peruvian government designed to support universal health coverage have also helped to promote free health care[27]. For wait times for care, and quality of care, slightly less than half of the participants described it as “regular” (average). The study in Piura[18] reported similar results, while the study in Trujillo[14] had a different outcome, with almost half of the participants (46%) reporting very long wait times. However, 83 or 61% of the participants in that study said the quality of care was good. Most of the respondents in this one reported not receiving any type of organized social support, whereas respondents from some of the poorest areas in China reported 48% received these types of services[25]. Although each person is responsible for finding ways to obtain better living conditions, access to these types of services improves the chances in attaining better health[25]. In many cases, barriers to enjoying good health go beyond individual dispositions and capacities[22].

One of the strengths of this study is that it included data from a large sample of men and women. We believe that our findings allow for better visualization of the magnitude of the problems and provide a strong reference point for future research evaluating older adults with similar characteristics and determining causalitycrelation among other variables.

The main limitation of this study was the restriction of the research to health networks belonging to the Ministry of Health of Peru (patients of other health facilities were not included). Therefore, despite the probabilistic sampling, the sample may not be representative of the entire population of the city of Chimbote. Another limitation is the risk of recall bias due to the use of self-reported data. However, whenever possible, the information provided by the study participants was corroborated.

Conclusions

Our research showed that 1) most of the participants had completed secondary studies, but this educational level was insufficient for access to better salary scales, and 2) a large proportion has their own home, and basic services (electricity, water, and sewage), but lives in overcrowded housing (more than three people per room). As described above, this is due to scarce economic income that does not allow this population to improve the distribution of space[21].

This research also found low consumption of alcoholic beverages and tobacco, but a high level of physical inactivity linked to a sedentary lifestyle, and high consumption of carbohydrates, which increases the risk of infectious and chronic diseases. Despite this risk, most of the study participants said they did not have regular medical checkups. These results highlight the need for the education sector to become involved in the health sector to improve population health[2].

Notes

Authorship contributions

MAVR, EZL, and JBP participated in the conception of the idea of the study. All authors participated in data collection, interpretation of results, drafting of the manuscript, and approval of the final version.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest concerning this article.

Funding sources

This study was funded by the Universidad Católica Los Ángeles de Chimbote.

From the editor

The original article was submitted in Spanish. This version is a copyedited translation provided by the authors and authorized by the journal to be published.