Estudios originales

← vista completaPublicado el 2 de agosto de 2021 | http://doi.org/10.5867/medwave.2021.07.8434

Desarrollo y validación de un instrumento para medir el estilo de vida de estudiantes de medicina

Development and validation of an instrument to evaluate medical students' lifestyle

Abstract

Introduction It is required to have validated instruments in health science students that identify unhealthy habits and assess the impact of educational interventions and programs aimed at promoting a healthy lifestyle.

Objective To evaluate the validity and reliability of an instrument to measure medical students' lifestyles.

Methods A lifestyle questionnaire was developed using the Delphi technique by a group of experts. The final questionnaire was applied to 332 students of the School of Medicine of the Ricardo Palma University in 2017. A preliminary examination was carried out to assess preconditions for construct validity—including the correlation matrix, the Kaiser Meyer Olkin statistic, and the Bartlett sphericity test. Factor analysis was used for construct validity, and the possible resulting factors were extracted through the principal component analysis. Cronbach's alpha coefficient was calculated to assess the instrument reliability.

Results In this study, 41.6% of participants were men with a mean age of 20 years (standard deviation = 3). The preconditions for the factor analysis were a Kaiser Meyer Olkin coefficient = 0.773 and a significant Bartlett sphericity test. For the 47 items of the final questionnaire, the factor analysis showed an explained variance of 56.7% with eigenvalues greater than one. Cronbach's alpha was 0.78. The final questionnaire could assume values between -23 to 151 points. Based on a cut point of 71 points, the prevalence of students with an unhealthy lifestyle was 73.6%.

Conclusion The developed instrument has acceptable validity and reliability to measure lifestyle in medical students. For external validation, studies in other university populations are suggested.

|

Main messages

|

Introduction

Lifestyle as a relevant element of health sciences has its origins in the Lalonde Report. This document emphasizes the importance of four determinants of human health: biology, the environment, lifestyle, and the health services organization [1].

Since then, different approaches to this concept have been proposed. Most authors agree in defining it as a person's way of life, based on two relevant determinants: living conditions and individual patterns (which include beliefs, decisions, motives, habits, and behaviors). These determinants lead to good health, an increased risk of illness or even death [2],[3]. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines a healthy lifestyle as a way of life that reduces the risk of becoming seriously ill or dying prematurely [4].

Epidemiological transition is understood as the complex and dynamic process of moving from predominant infectious disease mortality to a pattern of late morbidity and mortality associated with non-communicable diseases [5]. This epidemiological transition has emphasized the importance of lifestyle as an essential determinant of health. Therefore, the WHO developed the "Global Strategy on Diet, Physical Activity and Health" that emphasized the global epidemiological change in mortality in industrialized countries and the 25 conditions that lifestyle changes can prevent. In addition, it is highlighted the importance of a healthy lifestyle as a critical factor to be considered from a public health point of view [6].

Although the current epidemiological approach considers social determinants and their interactions with classical biological factors, health sciences have not consistently inquired into extrinsic factors beyond purely biological ones. As recently shown, lifestyle is one of the major determinants of chronic diseases. Its modification has an enormous potential to halt or slow down the natural course of the disease or even reverse it. In this context, lifestyle medicine emerges as a discipline aimed at preventing diseases and promoting the biopsychosocial integrity of the human being. It also seeks to interact synergistically with interventions on classical biological determinants [7],[8],[9],[10].

Several studies have evaluated the lifestyle of university students based on different instruments. One of the most widely used instruments in Latin America is the FANTASTIC questionnaire (family-friends, physical activity, nutrition, tobacco-toxins, alcohol, sleep-safety belt-stress, personality type, introspection, and career-work). This tool was developed to identify and measure the lifestyles of the general population at McMaster University in Canada to aid health promotion. The instrument has been adapted and validated in various Latin American settings following the original version designed by Wilson et al. [11],[12],[13],[14].

Despite describing behaviors and bad habits related to lifestyle, the results of this questionnaire showed high frequencies of the categories: acceptable, good, and excellent. These categories indicated a healthier lifestyle in university students in general and students from the health sciences careers, compared to healthy people attended by physicians [15],[16],[17],[18],[19],[20],[21],[22],[23]. However, the results have shown heterogeneity in different populations, and its use may not necessarily be handy for the health personnel or physicians in training in particular. The physician is a professional considered as a pillar of society that is in charge of promoting healthy lifestyles. The lifestyle of health science students could influence their professional recommendations when they are in practice. In addition, one would generally expect medical students to have a healthy lifestyle. However, a recent review [22],[24] concluded that lifestyle habits in this population need to be modified to achieve healthier lifestyles.

Interventions aimed at achieving this change require tools that allow lifestyle to be objectively quantified and assessed. Therefore, it is essential to have validated instruments that identify unhealthy habits and evaluate the impact of interventions and educational programs to promote a healthy lifestyle, which undergraduates are expected to teach in their future professional practice. This study aims to assess the validity and reliability of an instrument developed to measure lifestyle in medical students.

Methods

A prospective, observational, analytical study was created to develop and validate a questionnaire intended to measure medical students' lifestyles. For this purpose, 332 medical students from Ricardo Palma University were surveyed in 2017 in Lima, Peru. The reference population consisted of 900 students enrolled in the first academic semester of 2017 at the School of Medicine of Ricardo Palma University, corresponding to the first six years of the career.

A simple random sampling formula without replacement for finite populations was used to obtain a representative sample of this population. The proportion used was 50% to maximize the sample size, obtaining 270 students. We added a non-response rate of 15% to this value, resulting in a final sample of 311 students. The questionnaires were self-administered and filled out in person at the university during regular academic activities in students who did not refer to any active disease. First, content validity was performed, following construct validity and reliability, and finally, the ranges and categories of participants' lifestyles were determined.

Instrument

The instrument used in the surveys was a questionnaire developed at the Research Institute of Biomedical Sciences (INICIB) of the Ricardo Palma University for students pursuing a health science career. The first version of the questionnaire had 50 questions grouped into five domains oriented to measure lifestyle construct. These included: physical activity, eating habits, self-care, harmful habits and risk behaviors, and mental health. The instrument was designed with a Likert-type scale with five response options, which had a numerical value from one to five. The five response alternatives were: always (5), almost always (4), sometimes (3), rarely (2), and never (1), varying according to the respondent's level of agreement or disagreement. Each question or item was elaborated with a specific objective. These objectives would give us an insight into weak points or unhealthy behaviors to issue recommendations.

Content validity

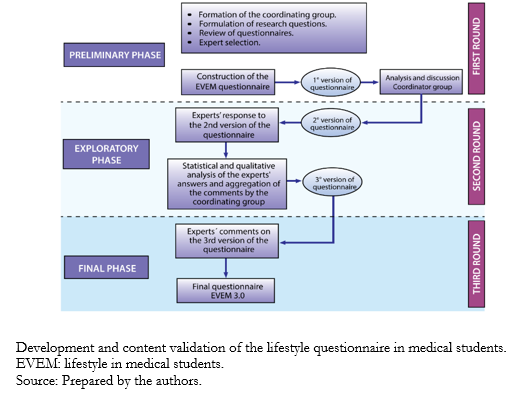

Using the Delphi technique [25], the instrument's content validity was carried out in three phases: preliminary, exploratory, and final (Figure 1).

Full size

Full size Preliminary phase

First, the coordinating group consisted of physicians specialized in lifestyles, including internists and mental health specialists. The coordinating group of the Biomedical Sciences Research Institute reviewed the literature focusing on the validation of lifestyle instruments. Similarly, the group of experts who would evaluate the first version of the questionnaire was subsequently selected. This group of experts comprised four mental health specialists, two internists, two physical medicine specialists, one rehabilitation specialist, and two nutritionists. After reviewing questionnaires through international databases (Google Scholar, SciELO, PubMed, ScienceDirect), the questionnaires relevant to lifestyle line of research were identified. Based on this identification, the questions for the construction of the questionnaire were formulated.

The first version of the questionnaire contained 63 items, which were sent to a group of experts to evaluate their content individually and anonymously. This first version was subjected to an initial pilot test with a group of 30 students. This sample size was determined by the group of experts following literature suggestions, in which 30 to 50 individuals for the application of pilot surveys were recommended[26]. This preliminary phase allowed changes to be made in the lexicon and grammatical construction of survey items. In addition, the areas, dimensions, or domains that would group the questions were clarified.

The first round of evaluation concluded with the qualitative adjustments made after the first pilot test, based on expert suggestions. All these changes were obtained based on consensus during face-to-face meetings. Consequently, a second version of the questionnaire was drafted and passed to the second round.

Exploratory phase

The second round consisted of the submission of the second version of the questionnaire to the experts. They were also in charge of assessing content validity using the incongruence index and the relevance index for each question. The group of experts evaluated the content of the proposed items from a qualitative approach with the proposed criteria according to the relevance, usefulness, pertinence, clarity, and wording in the statement of each item. In this process, possible biases and the relationship with their respective domains were detected. These biases included observations related to the self-care and harmful habits domains, which had to be reconsidered by consulting with other experts. The Delphi method culminated in the proposal of a questionnaire of 49 items grouped into five preliminary dimensions.

The expert's ratings in relevance, pertinence, usefulness, wording, and clarity for each question indicated that all values were at an optimum level of reliability (above 0.80). The instrument was then subjected to a new pilot test with 50 participants, and the results were sent to the experts for the final phase.

Final phase

In the third round, final adjustments were made, resulting in the final questionnaire version applied to measure lifestyle in medical students. Subsequently, psychometric evaluation and multivariate analysis were performed to demonstrate the construct validity of the designed instrument to determine the final number of questions to be included.

Construct validity and reliability

First, a preliminary exploration was carried out with SPSS-IBM 24.0 software to evaluate the preconditions for construct validity. One of these conditions was to evaluate in the correlation matrix whether most of the item-total correlations exceed a value of 0.3. In addition, the Kaiser Meyer Olkin statistic and Barlett's test of sphericity were determined. Imputation was not used in case of missing data.

As for construct validity, the principal component factor analysis was used. Its primary purpose is to define the underlying structure in a data matrix, identifying underlying dimensions called factors. An exploratory analysis was carried out because we worked under the hypothesis of factors specific to a population that had not been assessed in other research. In addition, the possible resulting factors were extracted using principal component analysis. Eigenvalues components that exceeded unity and a total accumulated variance greater than 50% were determined. A Cronbach's α coefficient was calculated in SPSS-IBM 24.0 software considering a value higher than 0.7 as an indicator of consistency to demonstrate the reliability of the instrument [24],[25],[26],[27].

Ethics

The ethics committee of the School of Medicine of the Ricardo Palma University approved the study.

Results

Preliminary analysis of the metric properties of the questionnaire items was performed. A Kaiser Meyer Olkin index of 0.773 and a P < 0.001 in Barlett's test of sphericity were obtained. The latter results indicated that it was feasible to perform the factor analysis on the questionnaire. The exploratory factor analysis of the 49-item questionnaire identified 13 principal components with eigenvalues greater than one, which explained 60.47% of the total accumulated variance. The variances of each component ranged from 11.7% for the first component to 2.17% for the last one. Two items that did not contribute significantly to any of the identified dimensions were excluded.

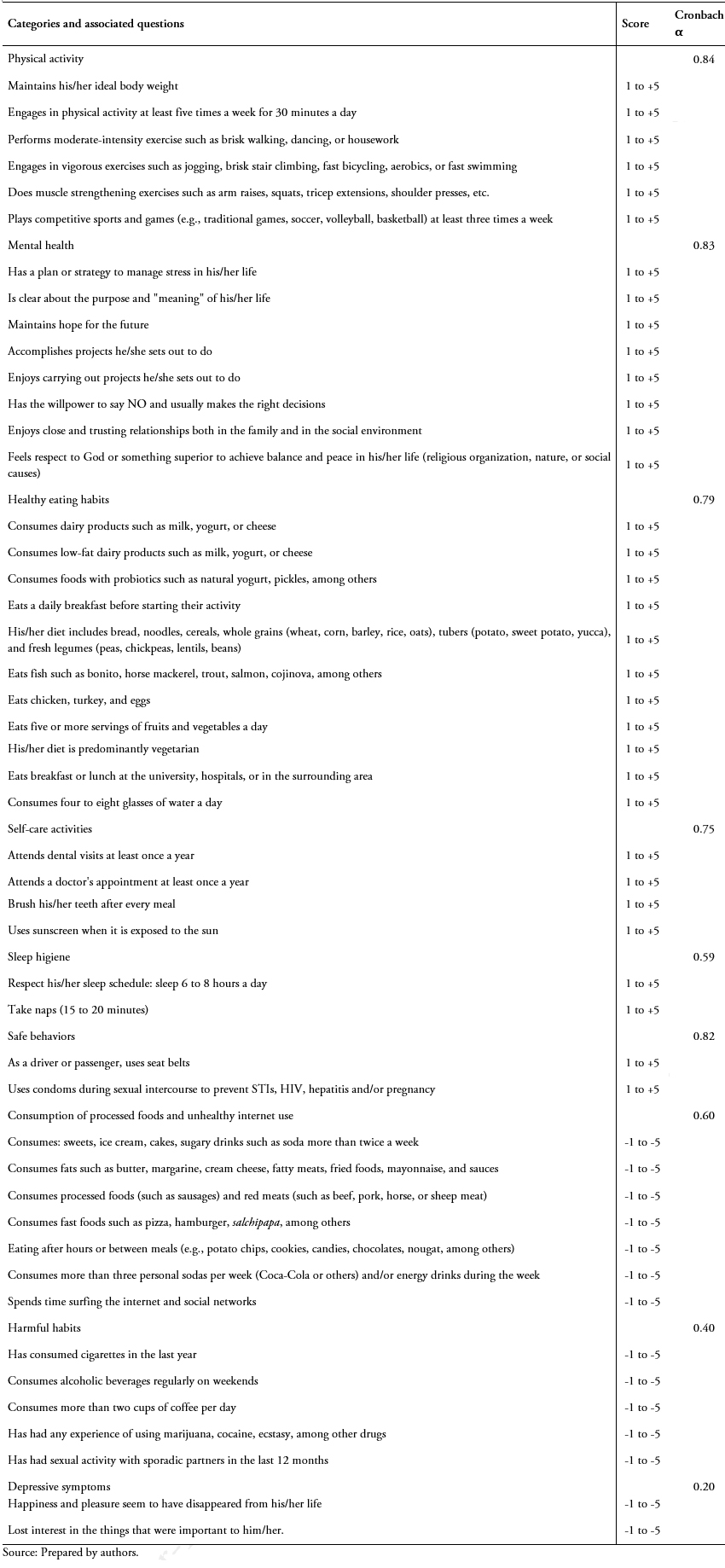

The final factor analysis identified 47 items grouped into 13 dimensions that explained 56.7% of the accumulated variance. The Annex (Tables 3 and 4) shows additional details of the factor analysis. Subsequently, an evaluation of these dimensions permitted grouping them according to their conceptual relationship. Thus, the final questionnaire had nine dimensions. The overall reliability of the final questionnaire of 47 questions was 0.78, measured by Cronbach's α. From the statistical point of view, the new questionnaire dimensions grouping is described below:

Component 1: Physical activity. It consisted of six items. This domain explained 9.22% of the total variance and presented a Cronbach's α value of 0.84.

Component 2: Mental Health. It consisted of eight items. This domain explained 11.7% of the total variance and presented a Cronbach's α value of 0.83.

Component 3: Consumption of processed foods and unhealthy internet use. It was composed of seven items. This domain explained 7.89% of the total variance and presented a Cronbach's α value of 0.79.

Component 4: Unhealthy habits. It consisted of five items. This domain explained 5.44% of the total variance and presented a Cronbach's α value of 0.75.

Component 5: Consumption of dairy products and natural probiotics. It consisted of three items. This domain explained 4% of the total variance and presented a Cronbach's α value of 0.72.

Component 6: Feeding patterns. It consisted of four items. This domain explained 3.48% of the total variance and presented a Cronbach's α value of 0.57.

Component 7: Depressive symptoms. It consisted of two items. This domain explained 3.30% of the total variance and presented a Cronbach's α value of 0.82.

Component 8: Self-care activities. It consisted of three items. This domain explained 2.97% of the total variance and presented a Cronbach's α value of 0.62.

Component 9: Fruit consumption and being vegetarian. It consisted of two items. This domain explained 2.77% of the total variance and presented a Cronbach's α value of 0.54.

Component 10: Sleep hygiene. It consisted of two items. This domain explained 2.69% of the total variance and presented a Cronbach's α value of 0.40.

Component 11: Safe behaviors. It consisted of two items. This domain explained 2.48% of the total variance and presented a Cronbach's α value of 0.20.

Component 12: Dental care. It consisted of only one item. This domain explained 2.37% of the total variance.

Component 13: Other eating habits. It consisted of two items. This domain explained 2.17% of the total variance and presented a Cronbach's α value of 0.14.

Subsequently, the categories were established by grouping the related components. Thus, components five, six, nine, and 13 were grouped in the healthy eating habits category (Cronbach's α = 0.59) and components eight and 12 within the self-care activities category (Cronbach's α = 0.6). The final questionnaire consisted of 47 questions (33 associated with positive scores and 14 with negative scores) divided into nine categories (Table 1).

Full size

Full size The minimum and maximum possible instrument scores were -23 and +151 points, respectively. If the total score of the instrument were closer to 151 points, it would indicate a better lifestyle. A score of 71 points was considered the cut-off point for a healthy lifestyle. This total score was obtained by having answers with a score of 3 or higher on the Likert scale (frequently, almost always, or always) to the questions with positive valuation, and less than 3 points (rarely or never) in the questions with a negative valuation.

Lifestyles distribution in the evaluated cohort of students

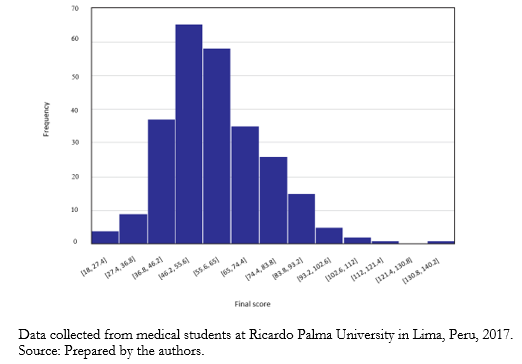

From 332 medical students, a mean score of 59.65 with a standard deviation of 17.1 was found. The distribution graphically approached normality, although slightly skewed to the right (skewness = 0.73). Normality tests showed a non-normal distribution (p < 0.01) (Figure 2).

Full size

Full size Discussion

The physician is responsible for exemplifying (and not just recommending) a healthy lifestyle in the community. This is probably one of the most powerful and underutilized interventions within our reach to achieve a good health status in the population, so medical students should be involved. Consequently, it is essential to assess medical student lifestyles to raise awareness and, if necessary, to promote a healthy lifestyle among them. The development and validation of our instrument have shown sufficient consistency to assess lifestyle in health science university students and, particularly, in medical students.

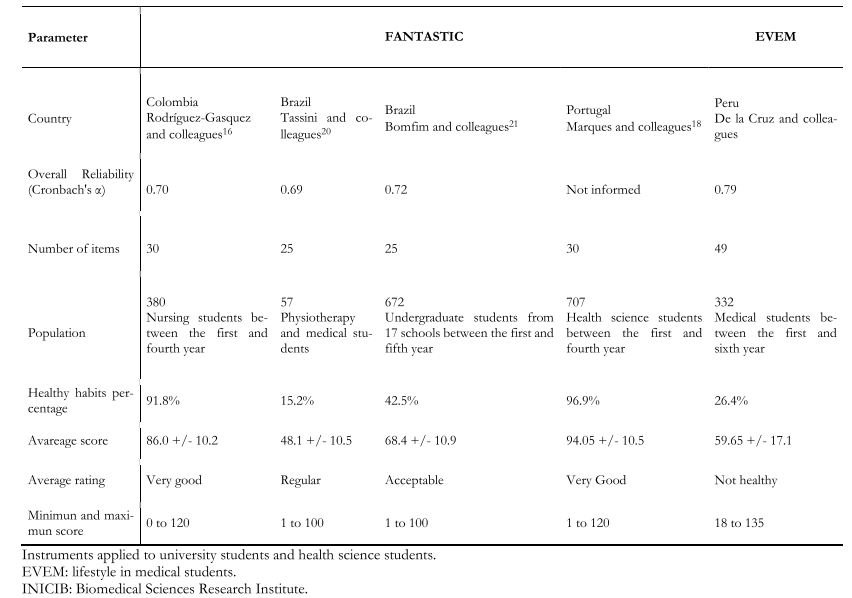

The internal consistency of the instrument evaluated through Cronbach's α was 0.78. This value is acceptable compared to previous adaptation and validation studies of lifestyle measurement instruments such as the FANTASTIC. The latter survey showed an α of 0.69 to 0.80 [13],[14],[15],[16],[17],[18],[19] in different populations. Four of the thirteen initial domains of the instrument showed reliability values above 0.7, which is the cut-off point for considering an adequate level of consistency [25]. The low Cronbach's α of the remaining seven domains may be caused by the values found during the analysis of the metric properties of items such as variability and in the item-total correlation. However, after recategorization into nine domains, most of the Cronbach's α showed values greater than 0.7. Therefore, the instrument can be considered a useful tool for screening and obtaining baseline information to improve the lifestyle of health science students.

The average lifestyle score in this study was 59.65 +/- 17.1 points, which is well below the optimal cut-off point to consider it healthy. This high frequency of unhealthy lifestyle habits has been previously described in Peruvian students, where 89% presented an unhealthy lifestyle through the FANTASTIC instrument [22]. In our study, this figure reached 73.6%. This difference could be attributed to the different items included in the questionnaires and because medical students may have different lifestyles compared to other university students.

On the other hand, the results disagree with those reported by Villar and colleagues [11], where 71% of participating workers reported a healthy lifestyle. Likewise, studies by Rodriguez-Gasquez et al. [16], Canova-Barrios [17], and Tassini et al. [20] − conducted in health science students − showed dissimilar results compared to our findings. These three studies found higher frequencies of students with very good, acceptable, and excellent lifestyles. Two Brazilian studies that used the FANTASTIC questionnaire show different results. The first study – conducted among undergraduate and graduate students [13] – found that most had acceptable and very good lifestyles; and the second study – conducted among medical and physiotherapy undergraduate students [20] − found that most had a regular lifestyle, although no student had a very good or excellent lifestyle.

The results of our questionnaire agree with the second study. Our work found many students with bad and lousy lifestyles, implying that the FANTASTIC questionnaire gives different results when classifying bad and lousy lifestyles in university students from careers other than health science. The heterogeneity of results among students from different careers justifies the development of instruments specifically for medical students. This limitation may also apply to other populations with comorbidities such as diabetes or hypertension linked to unhealthy lifestyles. Table 2 shows our findings compared with the FANTASTIC questionnaire results among university students. However, to accurately assess the similarity of results, it is suggested to compare both questionnaires in health science students in a prospective manner.

Full size

Full size Several studies conducted among medical students or health sciences students reveal a low prevalence of a healthy lifestyle. In this population, sedentary lifestyle, occasional or no physical exercise, followed by eating habits with low nutritional intake and a high intake of calories, sugars, and trans fats, stand out [15],[16],[17],[18],[19],[20],[21],[22],[23]. Therefore, these studies recommend behavioral intervention programs to adopt a healthy lifestyle, including the implementation of an undergraduate lifestyle course and planning strategies aimed at improving the health of future generations [28],[29],[30],[31]. The developed questionnaire can assess lifestyle in health science students quantitatively and contribute to these interventions.

The study's limitations include the fact that it was conducted among medical students from a single Peruvian institution. Therefore, we consider it essential to validate the instrument in several institutions, ideally among Latin American countries. The instrument is primarily intended to aid an objective evaluation of behaviors associated with healthy lifestyles. Although a cut-off point that inherently defines a healthy lifestyle may be questionable, we included a proposal that may be useful when comparing our scoring system with others studies.

On the other hand, some questions could be refined according to the evidence accumulated post hoc. For example, vegetarianism or consumption of nonfat dairy might not necessarily impact directly on morbidity or mortality. However, regardless of this controversy, these behaviors are associated with a healthy lifestyle, precisely our questionnaire's aim. Likewise, it should be considered that these results may not be extrapolated to other medical students in Peru or Latin America. For this reason, it is essential to validate the questionnaire in other health science and medical students, ideally through multicenter studies. Finally, the questionnaire could not be contrasted with a reference standard because there are no universally accepted criteria for defining a healthy lifestyle. However, we consider that the evaluation by a multidisciplinary team provides consistency to the results.

Conclusion

The instrument developed in this study has the psychometric properties to be considered a valuable, valid, and reliable tool for measuring lifestyle in medical students.

It is recommended that this instrument be prospectively validated in students of other careers and other countries.

Notes

Contributor roles

JDV: conceptualization, methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, research, resources, data processing, writing, visualization, supervision, project management. DO, LR: conceptualization, methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, research, data processing, writing, visualization. LC: conceptualization, methodology, validation, resources, writing, visualization. AS: conceptualization, methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, research, resources, writing, visualization.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Funding

The authors declare no external funding.

Competing interests

The authors completed the ICMJE conflict of interest statement and declared that they received no funds to complete this article. In the last three years, they had no financial relationships with organizations that may have an interest in the published article, and they have no other relationships or activities that may influence this publication. Forms can be requested by contacting the corresponding author or the journal.

Ethics

The research ethics committee of the School of Medicine of the Ricardo Palma University approved this study through file 2017-039 URP. The identity of each participant was coded in numbers maintaining anonymity and preserving the confidentiality of personal information.

Data sharing statement

The thesis related to the present research study can be found within the Ricardo Palma University repository database.

Language of submission

Spanish.

Annex 1

Annex.