Revisión sistemática

← vista completaPublicado el 22 de mayo de 2024 | http://doi.org/10.5867/medwave.2024.04.2910

Consideraciones metodológicas en el estudio de la discriminación laboral percibida y su asociación con la salud de los trabajadores y resultados ocupacionales: revisión panorámica

Methodological considerations in the study of perceived discrimination at work and its association with workers health and occupational outcomes: A scoping review

Abstract

Introduction Perceived workplace discrimination is a complex phenomenon involving unfair treatment in the workplace based on personal characteristics such as age, ethnicity, gender, or disability. The objective of this study is to explore the association of perceived workplace discrimination with health and occupational outcomes.

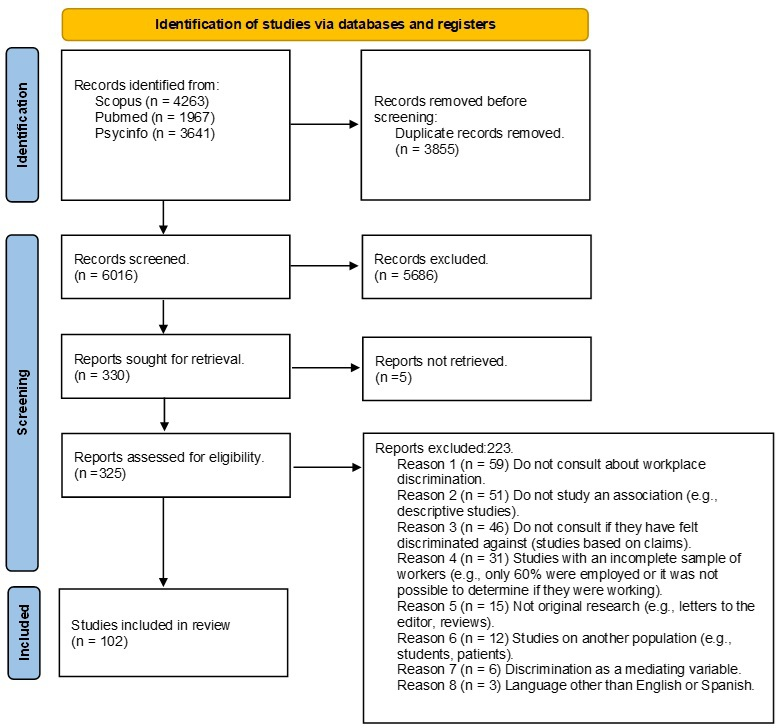

Methods Following the PRISMA-ScR guidelines and the Joanna Briggs Institute methodology, a scoping review of articles published between 2000 and 2022 was conducted in databases such as Pubmed, Scopus, and PsyInfo. Inclusion criteria focused on studies exploring perceived workplace discrimination among workers, excluding those on patients, students, or the general population, and articles not written in English or Spanish.

Results Of the 9,871 articles identified, 102 met the criteria and were analyzed. Research showed a progressive increase in the study of perceived workplace discrimination, with a majority of studies in North America and Europe and a predominance of cross-sectional designs. Most studies did not clearly define the concept of perceived workplace discrimination nor report the psychometric characteristics of the measurement instruments. A significant association was found between perceived discrimination and negative outcomes in workers' mental and physical health, as well as a negative impact on job satisfaction and an increase in absenteeism. Additionally, sociodemographic characteristics such as race/ethnicity, gender, and age influenced the perception of discrimination.

Conclusions This review confirms that perceived workplace discrimination significantly impacts the health and job satisfaction of workers, with particular detriment in minorities and women. Despite an increase in research over the last two decades, there remains a lack of consistency in the definition and measurement of the phenomenon. Most studies have used cross-sectional designs, and there is a notable absence of research in the Latin American context.

Main messages

- This article is the first scoping review that addresses the complexity of measuring perceived job discrimination and its association with health and occupational outcomes.

- The main finding of this review corresponds to the methodological gap, which highlights the lack of clear definitions and standardization in the measurements.

- The limitations of this work include the exclusion of studies that incorporate non-working populations that analyzed the variable job discrimination as a mediator in the hypothesis analyzed, the lack of studies in languages other than Spanish and English, the limitation to three databases, and the lack of a search for gray literature.

Introduction

Perceived discrimination is a complex concept. There are multiple characteristics associated with this phenomenon, such as the domains of life in which it can occur, the type of person who discriminates, the different forms of expression, and the different levels (individual, institutional, regional, national) at which it occurs [1]. The definitions of this construct usually agree that it is the perception of unfair treatment. For example, Pascoe and Richman [2] consider perceived discrimination as "a behavioral manifestation of a negative attitude, judgment or unfair treatment towards members of a group" [2]. Other authors emphasize that it can occur from institutional structures and policies or individual behaviors [3].

In the workplace, a widely used meaning is that which defines it as the unfair and harmful treatment of employees based on individual characteristics unrelated to job performance [4] but embody structural axes of discrimination such as age, ethnicity/race, gender, and disability, among others. Perceived discrimination has effects on the occupational and health outcomes of workers, with evidence indicating that the higher the level of perceived job discrimination, the higher the job stress; and the lower the "perceived fairness", the lower the "job satisfaction" and the more affected are physical and psychological health [5]. In addition, it would seem that only witnessing attitudes and behaviors of discrimination at work can influence the health of those who are not directly affected by them [5].

One of the great difficulties when investigating perceived discrimination is how it is measured since there is no single, objective way of doing it. From an epidemiological perspective, there are two ways to quantify discrimination’s effects on health at an individual level [6]. The first corresponds to an indirect measurement by assuming that certain groups with recognized negative discriminatory characteristics (subordinate groups) are discriminated against. This is the case of studies that compare a traditionally discriminated group versus a non-discriminated group and then analyze the differences in a given outcome, although neither group is asked about discrimination. The second does not assume discriminated and non-discriminated groups but measures it empirically by querying people for perceived discrimination using a self-report questionnaire [6].

Since there is no consensus on the use of a particular questionnaire or how consultation on perceived discrimination should be approached, self-report questionnaires are frequently used, although they are also associated with a number of difficulties. Some of the challenges posed by the measurement of perceived discrimination in the form of self-report are minimization bias (associated with lower reporting), vigilance bias (associated with higher reporting), few studies and inconclusive results about their psychometric properties, uncertainty about the optimal number of questions to improve validity, and the diversity of ways of asking questions, which even prevents comparison between studies. Added to this is the difference in approaches between the social and health sciences [3].

This article explores how perceived job discrimination has been investigated in the context of research on its association with health and occupational outcomes. Although previous research has addressed methodological aspects of "perceived job discrimination," it has done so from a different approach than the present article. Burkard et al. [7] developed a review of five instruments designed to measure discrimination, prejudice, and attitudes toward diversity in the workplace. Shen and Dhanani [8] reviewed the literature published between 2000 and 2014 about discrimination in the workplace to identify common trends regarding how discrimination is commonly studied and assessed. However, none of this research corresponds to a scoping review design. Based on the above, and to the authors' knowledge, this is the first scoping review to explore how perceived workplace discrimination has been investigated, considering its association with occupational health and outcomes.

Methods

This overview review was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA-ScR) guidelines [9] in conjunction with the methodology proposed by the Joanna Briggs Institute [10]. Prior to the development of the review, a protocol was developed which was registered in the international database International Platform of Registered Systematic Review and Meta-analysis Protocols, INPLASY (registration number: INPLASY202280009; doi:10.37766/inplasy2022.8.0009). Subsequently, this protocol was published [11] to improve research transparency and reduce the risk of reporting bias [12].

Eligibility criteria

Participants

This review considered articles investigating worker-perceived job discrimination and its association with occupational health or outcomes.

Concept

The concept that guided this review was "perceived job discrimination", considering the minimum commonality that different definitions present when discussing perceived discrimination. This concept refers to unfair treatment due to belonging to a particular social group or some characteristic of workers associated with discriminatory structuring axes [1,2,3,4]. Therefore, we included those studies where the term "perceived labor discrimination" was explicitly stated and also those studies that, although they did not explicitly state the term, through the reading of the methodology, it was possible to verify that the workers had been consulted if they had felt discriminated against in their workplaces.

Context

Only studies in occupational contexts were included (100% of the sample of workers). Therefore, studies on patients, students, or the general population were excluded. The geographic location of the sample did not limit the included studies. Studies that did not correspond to an original article and were written in a language other than English or Spanish were excluded.

Sources of information and search strategy

The primary studies were identified by searching the PubMed, Scopus, and PsycInfo databases published between 2000 and 2022. The search strategy considered the following terms: "employment discrimination" OR "workplace perceived discrimination" OR "perceived discrimination" OR "workplace discrimination" OR "work discrimination" OR "discrimination at work". This strategy was developed based on identifying relevant terms used in previous research.

Selection of data sources

After searching each of the databases, all identified records were uploaded to the Rayyan web application [13], where the removal of duplicate articles [14] was carried out along with a review of titles and abstracts. Before starting the review of titles and abstracts, a pilot test of the proposed eligibility criteria was performed with three articles to resolve disagreements before selection. After this, two investigators independently reviewed the titles and abstracts against the eligibility criteria, determining which article should enter the review. In those cases where there was disagreement between the reviewers on the title, abstract, or full-text review, it was resolved by discussion with a third reviewer. The search results and the reasons for excluding full-text articles that did not meet the eligibility criteria were recorded and subsequently reported in the PRISMA-ScR flowchart.

Data extraction process

Two independent reviewers extracted data from the articles selected for the overview review into a predefined template. This template considered the record based on the recommendation of the Joanna Briggs Institute [10]: author, year of publication, country of origin, objectives, study population and sample size, methods, results and details of these, and key findings related to the question of this review such as the name of the instrument for measuring discrimination, definition of discrimination, number of questions, among others.

Prior to data extraction, an extraction trial was conducted in which two of the researchers extracted data from the first three items. The extracted results were then compared, and the data extraction template changes were made. Once the data extraction template was obtained, the researchers extracted the corresponding records from all the articles.

Risk of bias assessment

Two investigators independently reviewed the methodological quality of each article using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) [15]. Studies were assessed according to the criteria of the referred tool based on the selected category. The response options in all study categories include "yes," "no," and "cannot say." The response "cannot say" indicates that insufficient information was provided in the study for a "yes" or "no" answer.

Results

Through the search for original articles in the databases above, 9871 articles were initially identified. Figure 1 shows the number of articles excluded at each stage and the final number of 102 articles that met the eligibility criteria.

Flow chart of the selected studies.

Characteristics of the selected studies

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the 102 articles published between 2000 and 2022 that investigated the association between perceived job discrimination and health or occupational outcomes of workers and as a dependent or an independent role in that association. A progressive increase in the production of articles over time is observed, reflecting a steady growth in the volume of research in the period analyzed. Regarding geographical distribution, about 60% of the research was conducted in North America, followed by 20% in Europe and 17% in Asia. The most commonly used design was the cross-sectional design, present in almost 90% of the articles. Only 8% had longitudinal designs. Concerning sample size, approximately 56% of the articles reported sample sizes ranging from 100 to 1000 participants, while 37% presented samples with more than 1000 participants. Regarding the industries studied, it was observed that 29% of the articles incorporated various industries, while 22% were conducted in healthcare settings. However, in 36% of the articles, it was not possible to identify the type of industry in which the workers in the sample belonged.

Characteristics of the measurement of perceived job discrimination

Table 2 shows some specific characteristics of the measurement of perceived job discrimination. In the methods section, 40% of the articles state that they used specific instruments, adapted from or based on previous research. On the other hand, only 10 (9.8%) articles developed instruments to evaluate perceived job discrimination. Notably, in almost half of the articles, no bibliographical reference is reported that would allow us to know the origin of the method of measuring discrimination.

It should be noted that 91% of the studies did not define the concept of perceived job discrimination when the participants were asked. The forms of application varied between online (35%), face-to-face (15%), mixed (12%) and telephone (6%) surveys. Most of the studies (63%) used between 2 and 25 questions in their questionnaires, 20% used only one question to measure perceived job discrimination, and for the remaining 17%, the number of questions used could not be identified.

Seventy-three percent of the items identified the reasons why discrimination occurs. Of these, one-half of the articles addressed a single reason for discrimination, and the other half of the studies explored two or more reasons for job discrimination. However, approximately 28% of the research did not explore the reason for perceived job discrimination.

In 64% of the studies, no reference was made to the psychometric characteristics of the instruments or any assessment that would allow the instrument’s validity to be established. Of those studies that did evaluate some characteristic, most focused on reliability, usually through Cronbach’s α coefficient. Similarly, in 65% of the articles, no information was provided when asking about the period in which the discrimination occurred, with 12 months being the most frequently used time frame when this was reported (26%).

Finally, in all the articles analyzed, no mention is made of the severity of the perceived discrimination, while only a meager proportion of these articles reference other important aspects of discrimination, such as the frequency with which it occurs (18%) and who perpetrates it (22%), with superiors and colleagues being considered the main perpetrators.

Association between perceived job discrimination and its influence on health and occupational outcomes

Of the total number of articles included in this review, 60 (58.8%) investigated the association between perceived job discrimination and various health and occupational outcomes (Table 3). In the health outcomes category, mental health is the main outcome studied in 38% of the articles, covering aspects such as depression [22,24,26,27,29,31,33,37,38,75], stress [16,18,19,32,35,36,45], general measures [16,17,18,19,21,30,34,35], anxiety [16,26,33], self-esteem [23,25], among others [20,28,33] (Table 4). Most of this research indicates that perceived job discrimination negatively affects the mental health of workers. Different research designs point to a statistically significant association between job discrimination and depressive symptoms [22,24,26,29], mainly in cross-sectional designs [27,33] but also in longitudinal designs [31,37]. Like depression, stress shows a significant relationship in most of the articles where this was explored and considering different contexts, whether assessing in male-dominated jobs [18], in migrant workers [32], or health professionals [35]. Finally, findings show that higher levels of race-based job discrimination predict lower levels of self-esteem [23].

Second, 17% of the articles reviewed addressed general health outcomes, evidencing that perceived job discrimination is negatively related to self-reported health [16,41], both when considering age discrimination [31] and race [23]. However, the presence of this effect is not uniform [44]. Some found the effect partly due to the samples used [43] or for a specific type of discrimination [23].

Third, 13% of the articles addressed physical health outcomes, considering different domains such as physical symptoms [16,38,39], general physical health [18,21], and specific pathologies such as low back pain [40]. The results show that an increase in perceived job discrimination negatively influences the physical health of workers [18,21,26,38,39].

To a lesser extent, aspects such as behaviors and health conditions were addressed, highlighting that female firefighters with high rates of discrimination were more likely to report problems with alcohol consumption [26], findings aligned with other research [45,104]. In addition, perceived job discrimination showed statistically significant associations with sleep problems, including insomnia, sleepiness, reduced duration, and severe sleep disturbances [16,35,47].

Concerning occupational health outcomes, the main findings are associated with job engagement and job satisfaction (33%). The findings demonstrate that perceived job discrimination, whether based on gender [18,50], age [31,60], sexual orientation [36,52], disability [55], racial/ethnic [51,53], or regardless of different reasons [33], is consistently linked to negative outcomes in job satisfaction. In second place are work-related mental health outcomes (12%). Some findings reveal that job discrimination significantly predicts job stress [26,50,51] and burnout [35,53,62]. Thirdly, results related to organizational conditions represent 10% of the studies, finding various ways to operationalize it as grievances [58], job mistreatment [63], work-family conflict [64], job turnover [65], and job strain [45,56,66]. According to these investigations, various relationships are observed. For example, no relationship was identified between perceived job discrimination and claims filed [58]. Conversely, perceived job discrimination favors job mistreatment in those who reported at least one form of discrimination [63], work-life conflict [64], and job turnover [65].

Finally, articles that investigated outcomes related to absenteeism account for 8%. Most of these show that perceived job discrimination favors absenteeism [33,53,98].

Association between sociodemographic characteristics and their influence on perceived job discrimination

We found 58 articles that explored various demographic characteristics of workers and their influence on perceived job discrimination (Table 4). The three most studied characteristics were race/ethnicity (55%), sex/gender (53%) and age (33%). Most studies on the influence of race/ethnicity on job discrimination indicate that race/ethnicity is a predictor of discrimination (81%). In general, black workers report significantly higher levels than whites in various work settings [76,77,78,79,80,81]. Likewise, nationality plays a similar role, with evidence that foreign nurses experience higher levels of discrimination than native nurses [82]. This trend is also observed in non-Irish foreign workers compared to Irish [83], in Chinese workers compared to whites [84], in Nepalese workers compared to Pakistani [85], and in visible and indigenous minorities compared to whites [86]. However, the rest of the studies do not support the significant influence of race on job discrimination (Table 4).

Similarly, most studies that evaluated differences between men and women reveal disparities in the outcome of employment discrimination, with women being the most affected (68%). Some findings show that women are 12 times more likely than men to perceive job discrimination [76], and female surgeons are three times more likely to report experiences of job discrimination than men [99]. This trend of higher rates than the male counterpart is described in several investigations in the healthcare industry [80,81,87,88,100,101]. However, 26% of the studies did not find sex/gender to be a predictor of employment discrimination, and only 7% reported that men were more affected.

Concerning age, Table 4 shows the complex relationship of age as a predictor of perceived job discrimination. It was found that 31.6% of the studies identified age as a predictor of discrimination, with a tendency to increase with age. In the opposite direction, 31.6% of the studies identified age as a predictor, with more discrimination observed at younger ages. Another 31.6% of the studies did not find age to be a predictor of discrimination, and only one study reported a higher prevalence in workers of middle age (35 to 39 years).

Risk of bias assessment

The findings of the quality assessment of the studies based on the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool are presented in Annex 1. Overall, the included studies show moderate-high quality. However, more than half of the studies did not provide a clear definition or any assessment of the validity of the perceived job discrimination variable.

Discussion

Characteristics of the studies

The gradual increase in the production of articles on perceived job discrimination reflects the importance of this phenomenon in recent decades, possibly attributable to the growing public awareness of the negative impacts of discrimination on workers' health. In this context, the lack of studies in Latin America indicates a gap in research on perceived employment discrimination in this region. Undoubtedly, research is needed to explore these experiences to have local evidence to address this public health problem.

As expected, cross-sectional studies were the most used in terms of study designs. Their characteristics include speed of execution, speed in establishing associations, and low economic cost. However, their design does not allow causal relationships to be established, so their results should always be interpreted cautiously [105]. Thus, the need is identified to incorporate longitudinal designs that offer a deeper understanding of the evolution of the effects of discrimination in the long term and its possible modifications, even with intervention designs. In turn, including mixed designs can further enrich the understanding of this phenomenon.

It is important to mention that the effects of discrimination may manifest themselves uniquely in specific employment contexts. Related to this, research in particular industries can provide more detailed insight into workers' challenges in those settings. Different theoretical perspectives can be identified in the literature explaining how workplace demographics may influence workers' perceived discrimination [106]. For example, industries with a lower proportion of women and a masculinized organizational culture tend to favor job discrimination [107]. However, 36% of the articles do not state the industry to which the workers belonged, which points to a significant limitation since knowing the employment context in which discrimination occurs is crucial to understanding better the results. Therefore, future research should systematically provide this information.

Characteristics of the measurement of perceived employment discrimination

Studying perceived job discrimination is not easy due to the subjectivity component provided by the concept of "perception". An essential finding of this review is the lack of a definition of perceived job discrimination since more than 90% of the articles do not present a definition in the methodology or in their questionnaire. Those studies that did define it [19,62,65,80,82,88] identify two common elements: unfair, different, or unfavorable treatment, and the underlying reason for the discrimination, where all definitions refer to some reason such as age, race, sex, or belonging to a specific group of people. It was also possible to identify two axes along which these definitions differ. Some definitions emphasize a legal approach [88], and others indicate that discrimination implies treating people unequally "without an acceptable reason". In particular, this last element seems fundamental to discuss, since in the labor context decision-making is often based on workers' productivity. Therefore, we believe that a good way to define perceived labor discrimination is as "unfair or negative treatment of workers based on individual characteristics or membership in a social group and unrelated to job performance". This definition combines those critical elements described in the literature and identified in the review [1,2,3,4].

Another finding corresponds to the various instruments used to measure perceived job discrimination and the lack of standardization in these measurements. This poses challenges for comparability between studies and interpretation of the results. No single instrument is globally identified as the gold standard for measuring this construct. The few articles that used previously validated instruments were created to assess discrimination, usually considering a specific focus, either based on age [73], sexual orientation [95], accent when speaking [56], or race [108].

In line with previous research, there is a lack of disclosure of the psychometric characteristics of the instruments in a high percentage of studies. Regarding the absence of detailed information on the period in which discrimination occurs, half of the articles do not present bibliographic references associated with perceived job discrimination. The approach to discrimination in one or more questions prevents comparison between studies [3]. Thus, the studies raise questions about the reliability and validity of the measurements made, and future research should consider these elements. Probably, a difficult aspect to solve in the approach to discrimination is the number of questions. In addition, we also believe it is complex to determine whether to measure with a broad approach (without identifying the reasons for discrimination) or a specific approach (considering a specific reason for discrimination). From a practical perspective, it is important to consider the multiple forms of discrimination that can be found in the workplace. This would allow the incorporation of more complex approaches such as intersectionality, recognizing the structures of class, race, age, sex, and gender, among others, that intersect in workers' positions in a given industry, triggering discrimination and shaping more complex social inequalities [109].

Finally, the lack of systematic exploration of aspects such as perpetrator, frequency, and severity of discrimination in most studies suggests the need for greater attention to contextual factors that may influence experiences of perceived employment discrimination. These aspects have been previously described by pioneering discrimination researchers such as Nancy Krieger [1]. Therefore, incorporating these elements would allow to better capture the phenomenon and focus intervention strategies aimed at eliminating perceived employment discrimination.

Association between perceived job discrimination and its influence on occupational and mental health outcomes

The review reveals an inescapable association between perceived job discrimination and a wide range of worker health outcomes. Such an association aligns with previous research [2,5,110] and underscores the urgency of addressing mental health in the workplace. This requires following the recommendations of the World Health Organization (WHO) and the International Labor Organization (ILO), which indicate that stakeholders in the world of work (governments, employers, and workers) should create enabling environments for mental health-related change. Governments must ensure that labor laws are aligned with international human rights instruments and can provide for non-discrimination of workers with mental health problems. On the other hand, employers are responsible for complying with rights-based laws and implement non-discriminatory hiring and employment policies and practices. Therefore, governments, in close liaison with workers and employers, are charged with carrying out a critical role in facilitating supportive interventions [111].

The negative influence of perceived employment discrimination extends beyond the mental sphere and can impact the physical health of workers, which has also been described in previous reviews [5]. Occupational health outcomes consistently reveal that perceived job discrimination is linked to negative outcomes in job satisfaction, job stress, and burnout. These findings highlight the importance of adopting a holistic approach, addressing mental and physical health to ensure complete employee well-being; thus, organizational interventions that promote a healthy work environment and mitigate the adverse impacts of discrimination are necessary. An alternative is the total worker health approach [112], which allows prioritizing risk-free work environments for all workers by considering integrated interventions that collectively address workers' safety, health, and well-being.

Association between sociodemographic characteristics and their influence on perceived job discrimination.

Studying the influence of sociodemographic characteristics on job discrimination is essential for developing interventions that promote equitable and healthy work environments. Addressing disparities associated with sociodemographic characteristics, therefore, not only benefits affected workers but also contributes to building more inclusive and fair workplaces [113].

Limitations

Four important limitations can be identified. First, many studies were excluded because the samples were composed of students, of working-age populations who were not necessarily active at the time of asking or of a large percentage of unemployed. Thus, only studies that stated or from which it could be inferred that the participants were working in the period when they were asked about discrimination were included. Therefore, this review left out a large body of research that studied perceived employment discrimination. The work experiences of these participants could be considerably different and contribute to bias in the research. Second, those studies that did path analysis and in which the job discrimination variable was only considered as a mediator in the study hypotheses were not included. Third, only studies in English and Spanish were considered, which diminishes the ability to examine research associated with employment discrimination published in other languages. Fourth, only three databases were considered, and a search of the gray literature was not conducted. We believe that the vast majority of the literature is contained in the findings of this review, but the loss of literature of interest is possible.

Conclusion

This scoping review shows that research on perceived employment discrimination has evolved significantly over the last two decades, with a progressive increase in the number of studies conducted. However, there is a notable lack of consistency in defining and measuring the concept. Most of the studies did not provide a clear definition or details on the characteristics associated with the instruments' validity. Other characteristics, such as insufficient exploration of aspects such as the perpetrator, and frequency and severity of perceived job discrimination, suggest an important area for improvement. In addition, it is necessary to diversify the study designs to advance in understanding this phenomenon, exploring beyond the cross-sectional design.

On the other hand, a lack of studies in Latin America is identified, underscoring the importance of expanding research to different geographical and cultural contexts. These gaps in methodology indicate an urgent need to establish standardized protocols and more precise definitions to improve the quality and comparability of future research.

Finally, the evidence gathered clearly demonstrates that perceived job discrimination has a significant impact on the mental and physical health of employees and various occupational aspects. This phenomenon not only contributes to health problems such as stress and depression but also negatively affects job satisfaction and job commitment.

In addition, sociodemographic characteristics, including race/ethnicity, gender, and age, play a crucial role in the experience and perception of job discrimination. It is observed that certain groups, especially ethnic minorities and women, are more susceptible to face discrimination in the workplace. Thus, the importance of addressing discrimination from a public health perspective that allows the implementation of inclusive and equitable work policies and practices to promote healthier and more productive work environments is highlighted.