Resúmenes Epistemonikos

← vista completaPublicado el 25 de febrero de 2016 | http://doi.org/10.5867/medwave.2016.6379

¿Es necesario agregar aminoglicósidos al tratamiento con betalactámicos en pacientes con cáncer y neutropenia febril?

Is the addition of aminoglycosides to beta-lactams in cancer patients with febrile neutropenia needed?

Abstract

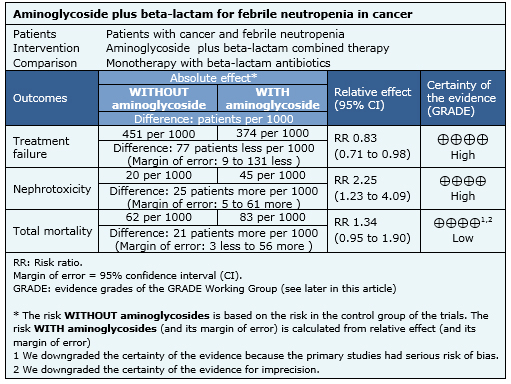

It is still controversial if the combined use of beta-lactam antibiotics and aminoglycosides has advantages over broad-spectrum beta-lactam monotherapy for the empirical treatment of cancer patients with febrile neutropenia. Searching in Epistemonikos database, which is maintained by screening 30 databases, we identified three systematic reviews including 14 pertinent randomized trials. We combined the evidence using meta-analysis and generated a summary of findings table following the GRADE approach. We concluded the combination of beta-lactam antibiotics and aminoglycosides probably does not lead to a reduced mortality in febrile neutropenic cancer patients and it might increase nephrotoxicity.

Problem

Patients with cancer have predisposition to infections that increase morbidity and mortality. Many factors contribute to this risk, including neutropenia and the anatomic barrier disruption due to the underlying disease or its treatment. This has led to the use of empirical antibiotics when infection is suspected in patients with fever, before isolating the pathogen or determining its sensitivity.

The combination of beta-lactams and aminoglycosides has been one of the most widely used treatment options. It aims to increase antimicrobial spectrum, and a synergistic effect has been proposed too, preventing the appearance of intra-treatment resistance. Currently, there are alternatives for beta-lactam monotherapy with wide coverage over gram positive and negative bacteria, which can be used to replace combinations. Furthermore, the addition of aminoglycosides increases adverse effects risk, mainly renal toxicity.

Methods

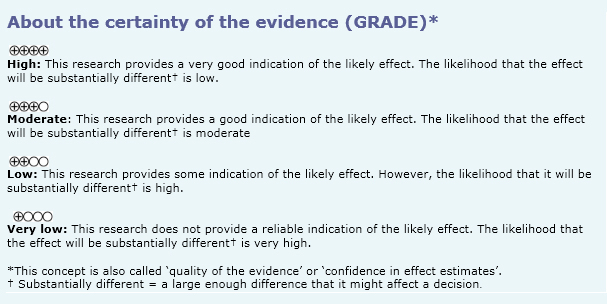

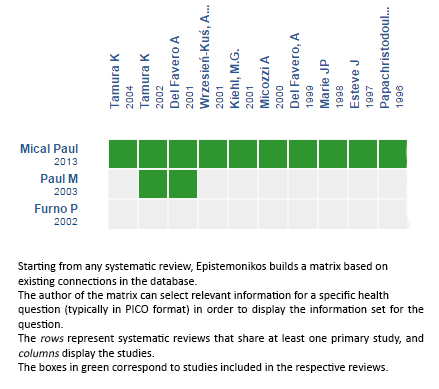

We used Epistemonikos database, which is maintained by screening more than 30 databases, to identify systematic reviews and their included primary studies. With this information, we generated a structured summary using a pre-established format, which includes key messages, a summary of the body of evidence (presented as an evidence matrix in Epistemonikos), meta-analysis of the total of studies, a summary of findings table following the GRADE approach and a table of other considerations for decision-making.

|

Key messages

|

About the body of evidence for this question

|

What is the evidence. |

We found three systematic reviews [1],[2],[3], including 14 randomized controlled trials reported in 17 references [4],[5],[6],[7],[8],[9],[10],[11],[12],[13],[14], |

|

What types of patients were included |

Eleven studies [6],[7],[10],[11],[14],[15],[16],[17],[18], Six studies [6],[7],[8],[9],[14],[18] included patients with hematologic malignancy, one study [10] included patients with solid tumors and six studies [4],[11],[15],[17],[19],[20], included both. In three studies [4],[8],[14] patients with bone marrow transplantation were included. Most of the studies considered patients with moderate neutropenia (<1000 leukocytes/mm3) and five studies [4],[6],[8],[9],[11] included patients with severe neutropenia. |

|

What types of interventions were included |

All included studies compared combination therapy (beta-lactam plus aminoglycosides) versus monotherapy with the same beta-lactam. All studies used a beta-lactam with antipseudomonic activity (piperaciline-tazobactam, cefepime, ceftazidime, cefoperazone and imipenem) and 12 of 14 studies [4],[6],[7],[10],[11],[14],[15],[16],[17], |

|

What types of outcomes |

The main outcomes were overall mortality, mortality related to infection, treatment failure and nephrotoxicity. |

|

We found three systematic reviews [5], [6], [7], including 14 studies reported in 21 references [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28]. Eight studies correspond to randomized controlled trials (15 references [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [16], [17], [19], [21], [22], [23], [24], [26], [27]). This table and the summary in general are based on the latter. One study [15] did not contribute data to any of the outcomes of interest. |

Summary of findings

The information about the effects of the association between aminoglycosides and beta-lactams in cancer patients with febrile neutropenia is based on 14 randomized controlled trials that included 2670 patients. Fourteen studies reported treatment failure, ten studies overall mortality [4],[6],[7],[9],[14],[15],[16],[18],[19],[20], seven studies measured mortality related to infection [4],[6],[9],[14],[15],[16],[18],[20] and eight studies reported nephrotoxicity [6],[7],[10],[11],[14],[17],[18],[19].

- The addition of aminoglycosides to beta-lactams in cancer patients with febrile neutropenia reduces treatment failure. The certainty of the evidence is high.

- The addition of aminoglycosides to beta-lactams in cancer patients with febrile neutropenia increases nephrotoxicity. The certainty of the evidence is high.

- The addition of aminoglycosides to beta-lactams in cancer patients with febrile neutropenia probably increases mortality, compared to monotherapy with the same beta- lactam. The certainty of the evidence is low.

Other considerations for decision-making

|

To whom this evidence does and does not apply |

|

| About the outcomes included in this summary |

|

| Balance between benefits and risks, and certainty of the evidence |

|

| Resource considerations |

|

|

Differences between this summary and other sources |

|

| Could this evidence change in the future? |

|

How we conducted this summary

Using automated and collaborative means, we compiled all the relevant evidence for the question of interest and we present it as a matrix of evidence.

Follow the link to access the interactive version: Beta‐lactam versus the same beta‐lactam plus aminoglycoside for febrile neutropenic cancer patients

Notes

The upper portion of the matrix of evidence will display a warning of “new evidence” if new systematic reviews are published after the publication of this summary. Even though the project considers the periodical update of these summaries, users are invited to comment in Medwave or to contact the authors through email if they find new evidence and the summary should be updated earlier. After creating an account in Epistemonikos, users will be able to save the matrixes and to receive automated notifications any time new evidence potentially relevant for the question appears.

The details about the methods used to produce these summaries are described here http://dx.doi.org/10.5867/medwave.2014.06.5997.

Epistemonikos foundation is a non-for-profit organization aiming to bring information closer to health decision-makers with technology. Its main development is Epistemonikos database (www.epistemonikos.org).

These summaries follow a rigorous process of internal peer review.

Conflicts of interest

The authors do not have relevant interests to declare.