Resúmenes Epistemonikos

← vista completaPublicado el 17 de mayo de 2017 | http://doi.org/10.5867/medwave.2017.6952

¿Es efectiva la ketamina endovenosa para el manejo del dolor postoperatorio en adultos?

Is intravenous ketamine effective for postoperative pain management in adults?

Abstract

Ketamine is a N-Metil-D-Aspartate receptor antagonist that has been used as adjuvant in the acute postoperative pain management because of its analgesic properties. However, its role is not clearly determined. To answer this question, we searched in Epistemonikos database, which is maintained by screening multiple information sources. We identified 19 systematic reviews including 226 randomized trials overall. We extracted data and generated a summary of findings table using the GRADE approach. We concluded intravenous ketamine probably has little or no effect in reducing postoperative pain.

Problem

Postoperative pain management is an important aspect in anesthesiology practice. Opioids are commonly used because of its effectiveness but they have adverse effects, such as nausea, vomiting, sedation and respiratory depression. One alternative strategy is to use adjuvant analgesics that through different pain pathways would reduce the incidence of undesirable effects.

The N-Metil-D-Aspartate receptor is an ionotropic glutamate receptor that has been implicated in pain mechanisms modulation. Ketamine is a non-competitive antagonist of N-Metil-D-Aspartate receptor and it has been used in low doses as adjuvant in postoperative pain management. However, its clinical use is still controversial because of its potential psychomimetic adverse effects such as nausea, vomiting and hallucinations.

Methods

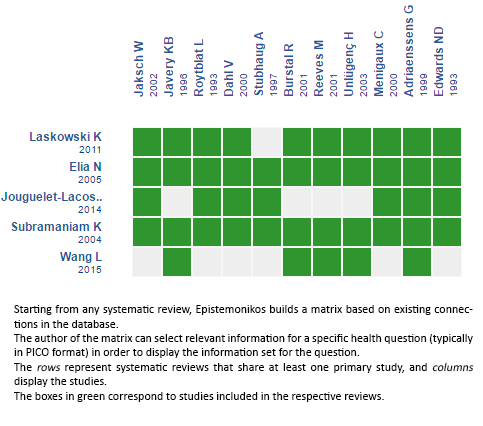

We used Epistemonikos database, which is maintained by screening multiple information sources, to identify systematic reviews and their included primary studies. With this information we generated a structured summary using a pre-established format, which includes key messages, a summary of the body of evidence (presented as an evidence matrix in Epistemonikos), a summary of findings table following the GRADE approach and a table of other considerations for decision-making.

|

Key messages

|

About the body of evidence for this question

|

What is the evidence. |

We found 19 systematic reviews [1-19] including 226 |

|

What types of patients were included* |

Thirty trials included patients undergoing abdominal surgery [20],[21],[22],[23],[24],[25],[26],[27],[28],[29],[30],[31], |

|

What types of interventions were included* |

All of the trials used intravenous ketamine. In 33 trials ketamine was administered in bolus [21],[22],[25], Ketamine was given during the preoperative period in 16 trials [21],[22],[25],[33],[40],[50],[54],[55],[59],[61],[66],[68], The doses ranged from 0.05 mg to 2 mg/kg for bolus, and 0.002 to 1 mg/kg/hour for continuous infusion. Thirty-three trials reported coadministration of opioids [22], Sixty-two trials compared to placebo [20],[21] [23],[25],[26], |

|

What types of outcomes |

The trials reported multiple outcomes, however they were grouped but the different systematic reviews as follows: postoperative pain, perioperative consumption of analgesia (opioids and others), time to need of first analgesic, surgical time, anesthesia time, postoperative nausea and vomiting and other adverse effects (such as unpleasant dreams, cognitive and psychological effects, hypotension and chills). |

* The information about primary studies is extracted from the systematic reviews identified, unless otherwise specified.

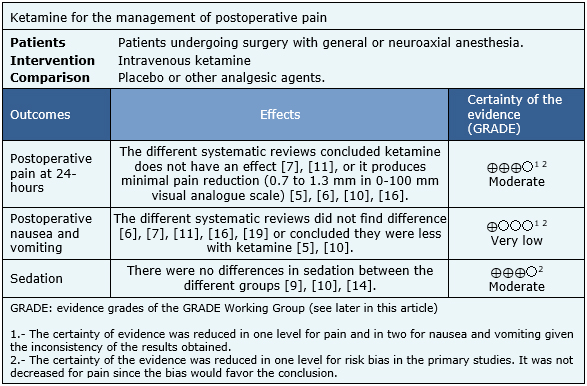

Summary of findings

It was not possible to extract sufficient information from the reviews identified as to rebuild the meta-analysis and the summary of findings table. Therefore, the information presented is based on the separate conclusions of the nine systematic reviews that performed meta-analyses for some of the outcomes of interest [5],[6],[7],[10],[11],[14],[16],[19]; pain at 24 hours after surgery [5],[6],[7],[10],[11],[16], postoperative nausea and vomiting [5],[6],[7],[10],[11],[16],[19] and sedation [9],[10],[14].

- Intravenous ketamine probably has little or no effect in reducing postoperative pain. The certainty of the evidence is moderate.

- It is not clear whether intravenous ketamine is associated to postoperative nausea and vomiting, because the certainty of the evidence is very low.

- Intravenous ketamine probably does not increase postoperative sedation. The certainty of the evidence is moderate.

Other considerations for decision-making

|

To whom this evidence does and does not apply |

|

| About the outcomes included in this summary |

|

| Balance between benefits and risks, and certainty of the evidence |

|

| What would patients and their doctors think about this intervention |

|

| Resource considerations |

|

|

Differences between this summary and other sources |

|

| Could this evidence change in the future? |

|

How we conducted this summary

Using automated and collaborative means, we compiled all the relevant evidence for the question of interest and we present it as a matrix of evidence.

Follow the link to access the interactive version: Ketamine for postoperative pain

Notes

The upper portion of the matrix of evidence will display a warning of “new evidence” if new systematic reviews are published after the publication of this summary. Even though the project considers the periodical update of these summaries, users are invited to comment in Medwave or to contact the authors through email if they find new evidence and the summary should be updated earlier. After creating an account in Epistemonikos, users will be able to save the matrices and to receive automated notifications any time new evidence potentially relevant for the question appears.

The details about the methods used to produce these summaries are described here http://dx.doi.org/10.5867/medwave.2014.06.5997.

Epistemonikos foundation is a non-for-profit organization aiming to bring information closer to health decision-makers with technology. Its main development is Epistemonikos database (www.epistemonikos.org).

These summaries follow a rigorous process of internal peer review.

Conflicts of interest

The authors do not have relevant interests to declare.