Epistemonikos summaries

← vista completaPublished on December 29, 2017 | http://doi.org/10.5867/medwave.2017.09.7121

Is intravenous lidocaine effective for decreasing pain and speeding up recovery after surgery?

¿Es efectiva la lidocaína endovenosa para disminuir el dolor y acelerar la recuperación postoperatoria?

Abstract

INTRODUCTION Lidocaine is widely used in anesthesia due to its multiple properties, including its role as analgesic. However, it is not entirely clear which are the real benefits of its use in the perioperative setting.

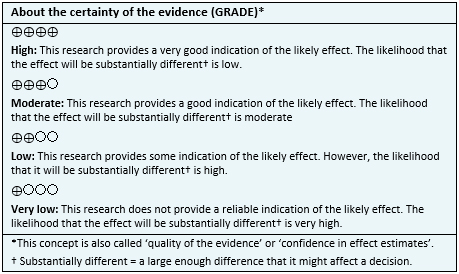

METHODS To answer this question we used Epistemonikos, the largest database of systematic reviews in health, which is maintained by screening multiple information sources, including MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane, among others. We extracted data from the systematic reviews, reanalyzed data of primary studies, conducted a meta-analysis and generated a summary of findings table using the GRADE approach.

RESULTS AND CONCLUSIONS We identified 15 systematic reviews including 53 studies overall, all of them randomized controlled trials. We concluded the use of intravenous perioperative lidocaine probably results in a clinically irrelevant difference in pain and length of hospital stay, but it probably prevents postoperative nausea and vomiting.

Problem

There are different alternatives used as adjuvants in the various anesthetics techniques, with the objective of diminishing postoperative symptoms and accelerating recovery. It has been proposed that lidocaine, a local anesthetic belonging to the group of the aminoamides which acts by inhibiting sodium channels, would have analgesics effects, among others, that would make it a good alternative in the surgical setting. Nevertheless, it is not yet clear whether its effects bring a real benefit for patients, and also if it is a safe intervention.

Methods

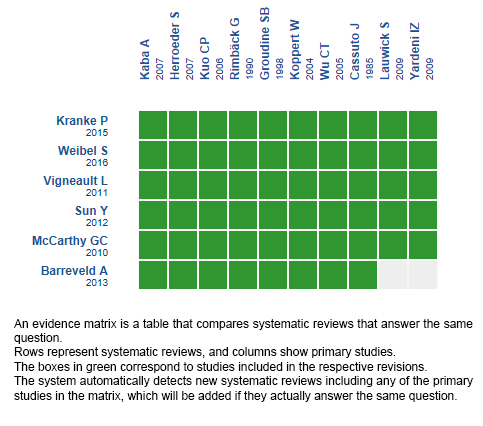

To answer the question, we used Epistemonikos, the largest database of systematic reviews in health, which is maintained by screening multiple information sources, including MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane, among others, to identify systematic reviews and their included primary studies. We extracted data from the identified reviews and reanalyzed data from primary studies included in those reviews. With this information, we generated a structured summary denominated FRISBEE (Friendly Summary of Body of Evidence using Epistemonikos) using a pre-established format, which includes key messages, a summary of the body of evidence (presented as an evidence matrix in Epistemonikos), meta-analysis of the total of studies when it is possible, a summary of findings table following the GRADE approach and a table of other considerations for decision-making.

|

Key messages

|

About the body of evidence for this question

|

What is the evidence. |

We identified 15 systematic reviews [1],[2],[3],[4],[5],[6],[7],[8],[9], One of the reviews [10] presented data from one trial that was not included in any other review (Harvey 2006), in a way in which it was not possible to reanalyze it. The reference to this trial is not included in the review, it was not possible to identify it by other means and the author did not reply after to our contact. |

|

What types of patients were included* |

Twenty five trials included adults from 18 to 75 years old [16],[17], Seven trials only included women [18],[21],[42],[44],[49],[50],[52], three included only men [26],[53],[60], the remaining 43 trials did not restrict by sex. Fourteen trials included ASA I-II patients [16],[18],[19],[28],[34],[36],[41], In 24 trials the patients underwent abdominal surgery; of these, 13 only included digestive surgery [17],[22],[24],[27],[28],[39],[41], Twenty-two trials excluded patients with chronic pain conditions, chronic pain treatments or pain treatment in the last week with any analgesic drug [19],[21],[22],[24],[25],[28],[34],[35],[39],[41],[42], |

|

What types of interventions were included* |

All of the trials used intravenous systemic lidocaine. Forty seven trials started lidocaine intraoperatively; of these, forty six initiated it before skin incision [16],[17],[18],[19],[20],[21],[22], Forty two trials used a lidocaine bolus (1 mg/kg to 3 mg/kg) followed by an infusion (20 μg/kg/min to 4 mg/min); from these, 17 maintained the infusion only during the intraoperative period [18], Four trials started lidocaine postoperatively; one as a bolus (1.5 mg/kg) and then continued with an infusion (2 mg/kg/h) for two hours [43]; of the remaining three, one used lidocaine infusion (60 mg/h) for 24 hours [54] and two a PCA without referring an end time [45],[46]. One trial started lidocaine preoperatively [58] with a bolus (1.5 mg/kg) followed by an infusion (2 mg/kg/h) only during the intraoperative period. It was not possible to extract data related to the characteristics from one trial [70] because it was included in only one systematic review [15], and the author did not reply after attempting to contact him. One trial was included in a systematic review with preliminary data before being published [35]. All of the trials compared lidocaine against placebo or no treatment. |

|

What types of outcomes |

The outcome were grouped by the systematics reviews as follows: Postoperative pain, intraoperative and postoperative analgesic consumption, chronic pain, opioid related adverse effects, postoperative nausea and vomiting, postoperative ileus and functional gastrointestinal recovery (evaluated by time to first flatus, feces, or bowel movement), length of hospital stay and length of post-anesthesia care unit stay, surgical complications, adverse events, mortality, cognitive outcomes, patient satisfaction, cessation of the intervention, systemic lidocaine toxicity, plasma levels of cytokines. |

* The information about primary studies is extracted from the systematic reviews identified, unless otherwise specified.

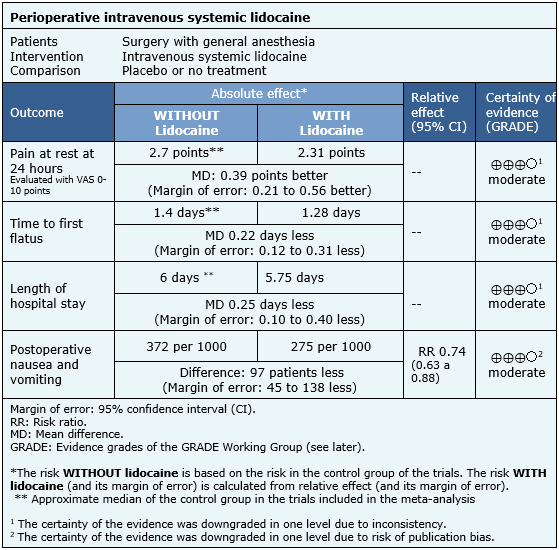

Summary of Findings

The information about the effects of the intravenous systemic lidocaine is based on 37 randomized trials including 2253 patients [16],[17],[18],[20],[21],[22],[23],[24],[25],[27],[28],[31],[32],[33],[35],[39],[40],[41],[42],[44],[48],[49],[51],[52],[53],[54],[57],[58],[59],[60],[61],[62],[63],[65],[66],[68],[69]. Twenty five trials reported the outcome pain at rest at 24 hours [16],[17],[18],[20],[22],[24],[25],[27],[28],[31],[35],[39],[41],[42],[44],[52],[53],[57],[58],[59],[60],[61],[65],[68],[69], 16 reported time to first flatus [18],[22],[24],[25],[28],[41],[51],[53],[54],[57],[59],[60],[63],[65],[68],[69], 24 measured length of hospital stay [18],[20],[22],[23],[24],[25],[27],[28],[32],[33],[39],[40],[41],[48],[51],[53],[54],[57],[58],[59],[60],[61],[62],[69] and 24 reported postoperative nausea and vomiting [16],[17],[18],[20],[21],[24],[25],[27],[28],[31],[35],[39],[41],[44],[49],[57],[58],[59],[60],[63],[65],[66],[68],[69].

The summary of findings is the following:

- The use of perioperative lidocaine probably leads to a clinically irrelevant reduction of pain at rest at 24 hours. The certainty of the evidence is moderate.

- The use of perioperative lidocaine probably leads to a clinically irrelevant reduction of time to first flatus. The certainty of the evidence is moderate.

- The use of perioperative lidocaine probably leads to a clinically irrelevant reduction of length of hospital stay. The certainty of the evidence is moderate.

- The use of perioperative lidocaine probably prevents postoperative nausea and vomiting. The certainty of the evidence is moderate.

Other considerations for decision-making

|

To whom this evidence does and does not apply |

|

| About the outcomes included in this summary |

|

| Balance between benefits and risks, and certainty of the evidence |

|

| Resource considerations |

|

| What would patients and their doctors think about this intervention |

|

|

Differences between this summary and other sources |

|

| Could this evidence change in the future? |

|

How we conducted this summary

Using automated and collaborative means, we compiled all the relevant evidence for the question of interest and we present it as a matrix of evidence.

Follow the link to access the interactive version: Intravenous lidocaine versus placebo or no treatment on perioperative analgesia

Notes

The upper portion of the matrix of evidence will display a warning of “new evidence” if new systematic reviews are published after the publication of this summary. Even though the project considers the periodical update of these summaries, users are invited to comment in Medwave or to contact the authors through email if they find new evidence and the summary should be updated earlier.

After creating an account in Epistemonikos, users will be able to save the matrixes and to receive automated notifications any time new evidence potentially relevant for the question appears.

This article is part of the Epistemonikos Evidence Synthesis project. It is elaborated with a pre-established methodology, following rigorous methodological standards and internal peer review process. Each of these articles corresponds to a summary, denominated FRISBEE (Friendly Summary of Body of Evidence using Epistemonikos), whose main objective is to synthesize the body of evidence for a specific question, with a friendly format to clinical professionals. Its main resources are based on the evidence matrix of Epistemonikos and analysis of results using GRADE methodology. Further details of the methods for developing this FRISBEE are described here (http://dx.doi.org/10.5867/medwave.2014.06.5997)

Epistemonikos foundation is a non-for-profit organization aiming to bring information closer to health decision-makers with technology. Its main development is Epistemonikos database (www.epistemonikos.org).

Potential conflicts of interest

The authors do not have relevant interests to declare.