Epistemonikos summaries

← vista completaPublished on August 6, 2018 | http://doi.org/10.5867/medwave.2018.04.7236

Does vitamin C prevent the common cold?

¿Previene la vitamina C el resfrío común?

Abstract

INTRODUCTION The common cold is one of the most common diseases. It is generally believed that the consumption of vitamin C prevents its appearance, but the actual efficacy of this measure is controversial.

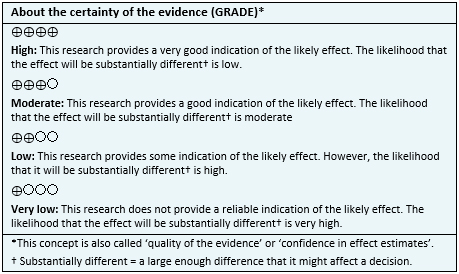

METHODS To answer this question we used Epistemonikos, the largest database of systematic reviews in health, which is maintained by screening multiple information sources, including MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane, among others. We extracted data from the systematic reviews, reanalyzed data of primary studies, conducted a meta-analysis and generated a summary of findings table using the GRADE approach.

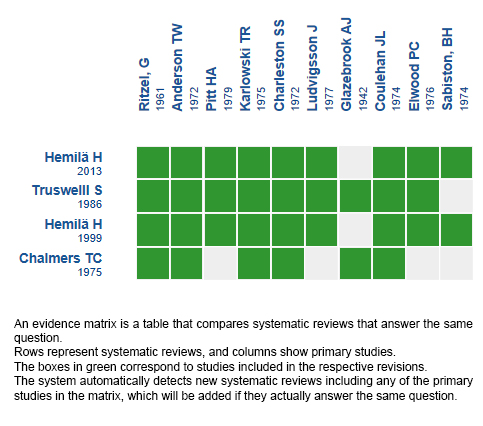

RESULTS AND CONCLUSIONS We identified eight systematic reviews including 45 studies overall, of which 31 were randomized trials. We concluded the consumption of vitamin C does not prevent the incidence of common cold.

Problem

The common cold is one of the most common diseases in the general population. The term "common cold" does not refer to a specific condition, but to a group of symptoms such as nasal obstruction, sore throat, cough, lethargy and asthenia, with or without fever. These symptoms have multiple etiological agents such as rhinovirus, adenovirus, syncytial virus, etc. Despite the benign nature of this disease, it leads to a substantive economic burden in terms of medical consultation, treatment, and work or school absenteeism [1].

On the other hand, effective alternatives to prevent this condition are not available, and the efforts to develop a vaccine have been fruitless.

Vitamin C is usually perceived as an effective, harmless and inexpensive therapeutic alternative. Its use began in the early 30s and in the 70s it became widespread when the Nobel Prize winner, Linus Pauling, concluded that the use of vitamin C could prevent and relieve the common cold [1]. It is thought that vitamin C could improve the functioning of the immune system through various mechanisms [2]: phagocytes and lymphocytes concentrate vitamin C in levels up to 100 times higher than plasma, suggesting it has a role in the immune system; vitamin C increases the response of T lymphocytes and interferon levels.

However, although the effects on the immune system are well reported, it is not clear whether the intake of vitamin C for the prevention of the common cold translates into a clinically relevant benefit.

Methods

To answer the question, we used Epistemonikos, the largest database of systematic reviews in health, which is maintained by screening multiple information sources, including MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane, among others, to identify systematic reviews and their included primary studies. We extracted data from the identified reviews and reanalyzed data from primary studies included in those reviews. With this information, we generated a structured summary denominated FRISBEE (Friendly Summary of Body of Evidence using Epistemonikos) using a pre-established format, which includes key messages, a summary of the body of evidence (presented as an evidence matrix in Epistemonikos), meta-analysis of the total of studies when it is possible, a summary of findings table following the GRADE approach and a table of other considerations for decision-making.

|

Key messages

|

About the body of evidence for this question

|

What is the evidence. |

We found eight systematic reviews [2],[3],[4],[5],[6], |

|

What types of patients were included* |

The trials evaluated adults and children. Eighteen trials [10],[12],[17],[18], [19],[20],[21],[22],[23],[24],[27], |

|

What types of interventions were included* |

All trials evaluated supplementation with oral doses higher than 0.08 g/day of vitamin C. Nine trials [10],[17],[18],[22],[31],[32],[34],[36],[37] administered low dose of vitamin C, in a range of 0.08 to 0.6 g/day. Ten trials 1 g/day [11],[12],[19],[20],[23],[25],[26],[28],[29],[30], four trials 2 g/day [16],[21],[24],[38] and one trial 3 g/day [27]. All trials compared against placebo. |

|

What types of outcomes |

The different trials measured multiple outcomes such, which were pooled by the systematic reviews as follows: incidence, duration and severity of the cold, among others. The follow-up period ranged from 3 weeks to 36 weeks. |

* The information about primary studies is extracted from the systematic reviews identified, unless otherwise specified.

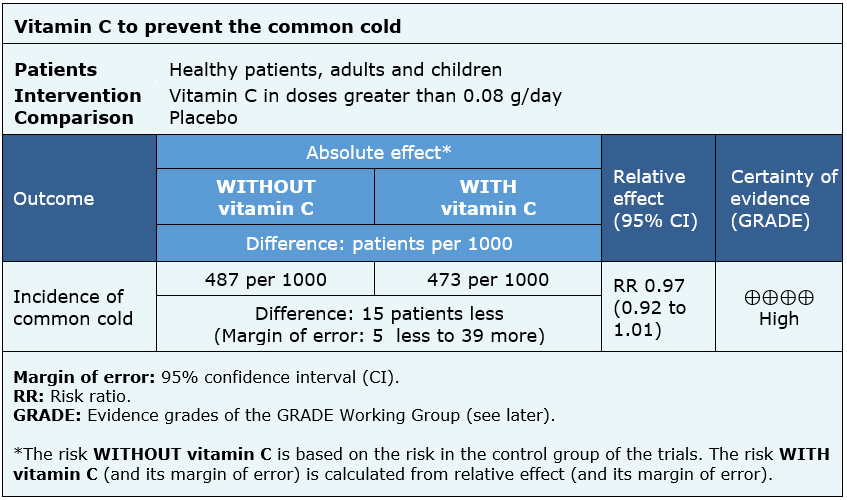

Summary of findings

The information of the effects of vitamin C in the prevention of common cold is based on 18 randomized trials [10],[12],[16],[17],[19],[20],[21],[22],[24],[25],[26],[28],[29],[30],[32],[34],[36],[37], which include 8472 patients in total. All trials measured the incidence of common cold during a specific time interval (8,472 patients).

The summary of findings is as follows:

- The consumption of vitamin C does not prevent the incidence of common cold. The certainty of the evidence is high.

| Following the link to access the interactive version of this table (Interactive Summary of Findings – iSoF) |

Other considerations for decision-making

|

To whom this evidence does and does not apply |

|

| About the outcomes included in this summary |

|

| Balance between benefits and risks, and certainty of the evidence |

|

| Resource considerations |

|

| What would patients and their doctors think about this intervention |

|

|

Differences between this summary and other sources |

|

| Could this evidence change in the future? |

|

How we conducted this summary

Using automated and collaborative means, we compiled all the relevant evidence for the question of interest and we present it as a matrix of evidence.

Follow the link to access the interactive version: Vitamina C for the prevention of common cold

Notes

The upper portion of the matrix of evidence will display a warning of “new evidence” if new systematic reviews are published after the publication of this summary. Even though the project considers the periodical update of these summaries, users are invited to comment in Medwave or to contact the authors through email if they find new evidence and the summary should be updated earlier.

After creating an account in Epistemonikos, users will be able to save the matrixes and to receive automated notifications any time new evidence potentially relevant for the question appears.

This article is part of the Epistemonikos Evidence Synthesis project. It is elaborated with a pre-established methodology, following rigorous methodological standards and internal peer review process. Each of these articles corresponds to a summary, denominated FRISBEE (Friendly Summary of Body of Evidence using Epistemonikos), whose main objective is to synthesize the body of evidence for a specific question, with a friendly format to clinical professionals. Its main resources are based on the evidence matrix of Epistemonikos and analysis of results using GRADE methodology. Further details of the methods for developing this FRISBEE are described here (http://dx.doi.org/10.5867/medwave.2014.06.5997)

Epistemonikos foundation is a non-for-profit organization aiming to bring information closer to health decision-makers with technology. Its main development is Epistemonikos database (www.epistemonikos.org).

Potential conflicts of interest

The authors do not have relevant interests to declare.