Resúmenes Epistemonikos

← vista completaPublicado el 23 de noviembre de 2018 | http://doi.org/10.5867/medwave.2018.07.7344

Videojuegos como método de entrenamiento para las habilidades quirúrgicas laparoscópicas básicas

Video games as a method of training basic laparoscopic skills

Abstract

INTRODUCTION The use of video games has been proposed as an alternative to shorten the learning curve of basic laparoscopic skills. However, it is not yet clar how useful this practice is.

METHODS We searched in Epistemonikos, the largest database of systematic reviews in health, which is maintained by screening multiple information sources, including MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane, among others. We extracted data from the systematic reviews, reanalyzed data of primary studies, conducted a meta-analysis and generated a summary of findings table using the GRADE approach.

RESULTS AND CONCLUSIONS We identified three systematic reviews including eight primary studies, of which four were randomized trials. We concluded video games training could help shorten the learning curve of basic laparoscopic visuospatial skills measured in a virtual platform, but the certainty of the available evidence is low.

Problem

Both reduced training time with living patients and rapid technological progress have changed surgical training in recent years. New forms of training have been implemented, such as of simulators or virtual reality exercises, especially in the field of minimally invasive surgery. The practice of video games could help acquire surgical skills, since it involves fine motor skills and familiarity with the use of 2D images to represent 3D realities. The possibility of training these skills through video games provides a new alternative for improvement. Despite the enthusiasm generated by these new tools, the evidence supporting its actual efficacy is a matter of debate.

Methods

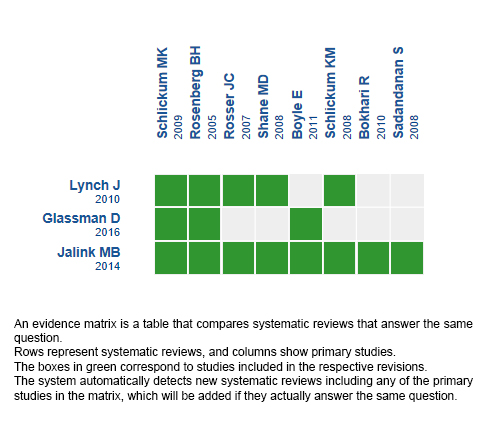

We searched in Epistemonikos, the largest database of systematic reviews in health, which is maintained by screening multiple information sources, including MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane, among others, to identify systematic reviews and their included primary studies. We extracted data from the identified reviews and reanalyzed data from primary studies included in those reviews. With this information, we generated a structured summary denominated FRISBEE (Friendly Summary of Body of Evidence using Epistemonikos) using a pre-established format, which includes key messages, a summary of the body of evidence (presented as an evidence matrix in Epistemonikos), meta-analysis of the total of studies when it is possible, a summary of findings table following the GRADE approach and a table of other considerations for decision-making.

|

Key messages

|

About the body of evidence for this question

|

What is the evidence. |

We found three systematic reviews [1],[2],[3] that included eight primary studies [4],[5],[6],[7],[8],[9],[10],[11], of which four were randomized trials [4],[5],[6],[7]. This table and the summary in general are based on the latter, since observational studies, even though reinforcing the positive association between use of video games and performance in basic laparoscopic skills, did not increase the certainty of the existing evidence. We only included systematic reviews evaluating mass-market consoles such as Nintendo Wii, Playstation or XBox. Thus, other video game formats such as virtual reality simulators or other virtual models were excluded. |

|

What types of participants were included* |

The trials included medical students without experience in laparoscopic surgery [5],[6] and novice residents of surgery [4],[7]. |

|

What types of interventions were included* |

The type of intervention used in all trials consisted of training with popular video games for a certain period of time. Three trials [4],[6],[7] measured the acquisition of basic laparoscopic skills with video games using a laparoscopic simulator and one trial [5] used an animal model. The average duration of game sessions was of 25-30 minutes per day. All trials compared against non-use of video games as a form of training, so in that period the control group did not practice with any method. |

|

What types of outcomes |

Each trial used a different method for measuring basic laparoscopic skills pre- and post-training with video games, both in virtual simulators or in animal models. In the different trials, follow-up was one [6], two [5], or five weeks [4],[7]. |

* The information about primary studies is extracted from the systematic reviews identified, unless otherwise specified.

Summary of findings

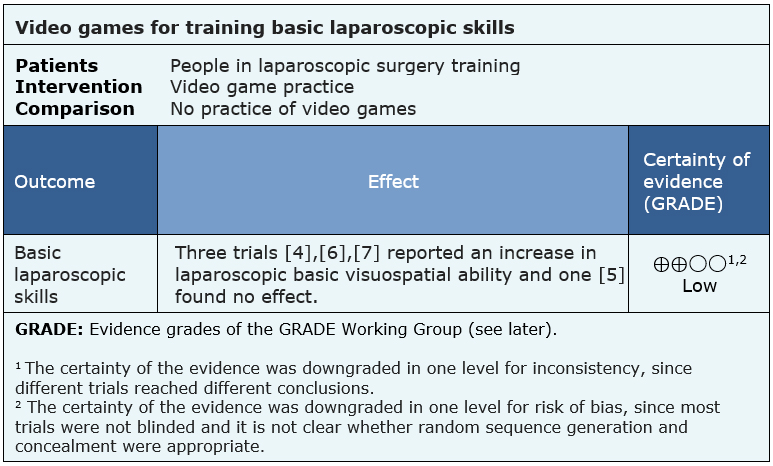

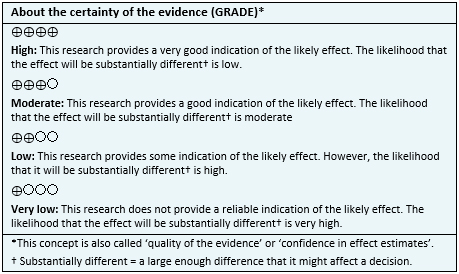

The information on the effect of video games as training for basic laparoscopic surgical skills is based on four randomized trials involving 99 surgeons or students [4],[5],[6],[7].

All trials reported laparoscopic skills, but none of the reviews presented data that could be re-analyzed or pooled in a meta-analysis, so the conclusions are presented as they were reported by the systematic reviews identified.

The summary of findings is as follows:

- The use of video games might improve basic laparoscopic skills in professionals or students in training, but the certainty of the evidence is low.

| Follow the link to access the interactive version of this table (Interactive Summary of Findings – iSoF) |

Other considerations for decision-making

|

To whom this evidence does and does not apply |

|

| About the outcomes included in this summary |

|

| Balance between benefits and risks, and certainty of the evidence |

|

| Resource considerations |

|

| What would patients and their doctors think about this intervention |

|

|

Differences between this summary and other sources |

|

| Could this evidence change in the future? |

|

How we conducted this summary

Using automated and collaborative means, we compiled all the relevant evidence for the question of interest and we present it as a matrix of evidence.

Follow the link to access the interactive version: Video games as a method of training basic laparoscopic skills.

Notes

The upper portion of the matrix of evidence will display a warning of “new evidence” if new systematic reviews are published after the publication of this summary. Even though the project considers the periodical update of these summaries, users are invited to comment in Medwave or to contact the authors through email if they find new evidence and the summary should be updated earlier.

After creating an account in Epistemonikos, users will be able to save the matrixes and to receive automated notifications any time new evidence potentially relevant for the question appears.

This article is part of the Epistemonikos Evidence Synthesis project. It is elaborated with a pre-established methodology, following rigorous methodological standards and internal peer review process. Each of these articles corresponds to a summary, denominated FRISBEE (Friendly Summary of Body of Evidence using Epistemonikos), whose main objective is to synthesize the body of evidence for a specific question, with a friendly format to clinical professionals. Its main resources are based on the evidence matrix of Epistemonikos and analysis of results using GRADE methodology. Further details of the methods for developing this FRISBEE are described here (http://dx.doi.org/10.5867/medwave.2014.06.5997)

Epistemonikos foundation is a non-for-profit organization aiming to bring information closer to health decision-makers with technology. Its main development is Epistemonikos database (www.epistemonikos.org).

Potential conflicts of interest

The authors do not have relevant interests to declare.