Epistemonikos summaries

← vista completaPublished on June 11, 2020 | http://doi.org/10.5867/medwave.2020.05.7732

Ibuprofen versus acetazolamide for prevention of acute mountain sickness

Ibuprofeno comparado con acetazolamida para prevención de mal agudo de montaña

Abstract

INTRODUCTION Acute mountain sickness is a common condition occurring in healthy subjects that undergo rapid ascent without prior acclimatization, as low as 2500 meters above sea level. The classic preventive agent has been acetazolamide, although in the last decade there has been evidence favoring ibuprofen. However, it is unclear which method is more efficient.

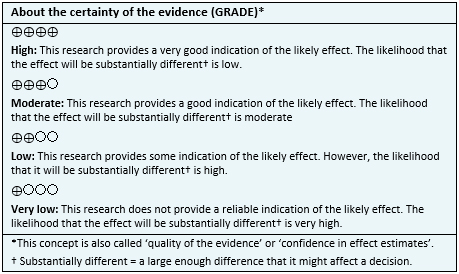

METHODS We searched in Epistemonikos, the largest database of systematic reviews in health, which is maintained by screening multiple information sources, including MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane, among others. We extracted data from the systematic reviews, reanalyzed data of primary studies, conducted a meta-analysis) and generated a summary of findings table using the GRADE approach.

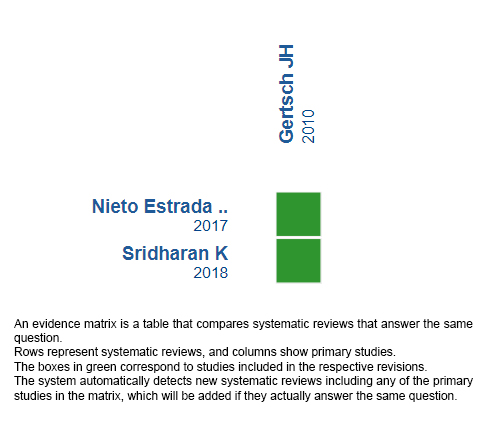

RESULTS AND CONCLUSIONS We identified two systematic reviews that included only one primary study, which is a randomized trial. We concluded it is not possible to establish whether ibuprofen is better or worse than acetazolamide because the certainty of evidence has been evaluated as very low.

Problem

Acute mountain sickness or high altitude illness is a condition that can arise when a subject ascents to more than 2500 meters above sea level without prior acclimatization. Classically, it presents as headache plus one of the following symptoms: anorexia, nausea, insomnia, fatigue or dizziness, and can progress to more severe forms of illness such as high altitude cerebral edema or high altitude pulmonary edema [1],[2].

Acetazolamide has been the most used pharmacological prevention. It inhibits carbonic anhydrase at renal level, causing bicarbonate excretion through urine and metabolic acidosis. Its effect would offset hyperventilation and respiratory alkalosis, thus favoring the physiological response to hypoxic stimuli. However, the minimum dose (from 250 mg to 750mg per day) is still controversial.

An alternative treatment that has gained support during the last years has been ibuprofen, due to its availability and easy access [4],[5],[6]. This drug inhibits the synthesis of prostaglandin, which increases microvascular permeability at the brain as a physiopathological mechanism of acute mountain sickness. However, it is unclear which treatment is more effective.

Methods

We searched in Epistemonikos, the largest database of systematic reviews in health, which is maintained by screening multiple information sources, including MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane, among others, to identify systematic reviews and their included primary studies. We extracted data from the identified reviews and reanalyzed data from primary studies included in those reviews. With this information, we generated a structured summary denominated FRISBEE (Friendly Summary of Body of Evidence using Epistemonikos) using a pre-established format, which includes key messages, a summary of the body of evidence (presented as an evidence matrix in Epistemonikos), meta-analysis of the total of studies when it is possible, a summary of findings table following the GRADE approach and a table of other considerations for decision-making.

|

Key messages

|

About the body of evidence for this question

|

What is the evidence. |

We found two systematic reviews [1],[2] that included one primary study [3], which is a randomized trial. |

|

What types of patients were included* |

The trial included healthy patients, between 18 to 65 years, at risk of developing acute mountain sickness; without prior acclimatization. Criteria of exclusion were use of NSAIDs or acetazolamide one to three days prior to enrollment, symptoms of acute mountain sickness or concomitant infection.[3] |

|

What types of interventions were included* |

The trial divided the participants into three groups: acetazolamide (75 mg tid), ibuprofen (600 mg tid) and placebo. All three groups had a prior three nights period of acclimatization [3]. |

|

What types of outcomes |

The trial measured multiple outcomes that were grouped in the systematic reviews as follows:

The follow-up was one day [3]. |

* The information about primary studies is extracted from the systematic reviews identified, unless otherwise specified.

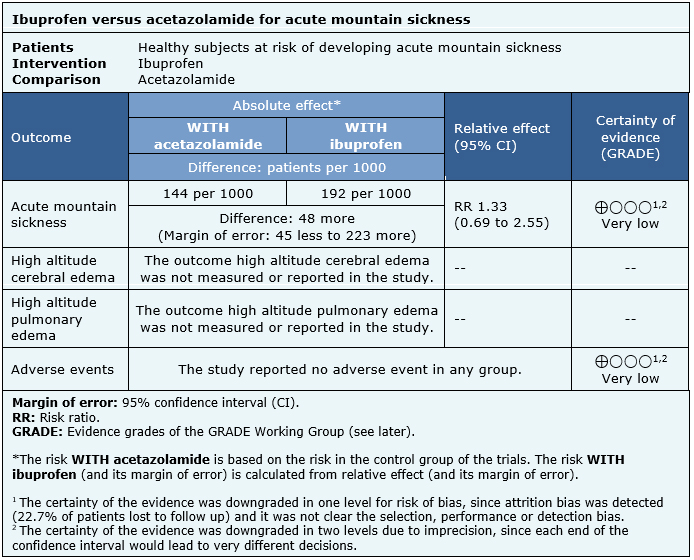

Summary of findings

The information about the effects of ibuprofen for prevention of acute mountain sickness is based on one randomized trial that included 343 subjects, from which 129 were randomized to ibuprofen, 125 to acetazolamide and 89 to placebo [3].

The summary of findings is as follows:

- We are uncertain whether ibuprofen is better or worse than acetazolamide for prevention of acute mountain sickness because the certainty of the evidence has been assessed as very low.

- The outcome high altitude cerebral edema was not measured or reported.

- The outcome high altitude pulmonary edema was not measured or reported.

- We are uncertain whether ibuprofen has more or less adverse events than acetazolamide for prevention of acute mountain sickness because the certainty of the evidence has been assessed as very low.

|

Follow the link to access the interactive version of this table (Interactive Summary of Findings – iSoF) |

Other considerations for decision-making

|

To whom this evidence does and does not apply |

|

| About the outcomes included in this summary |

|

| Balance between benefits and risks, and certainty of the evidence |

|

| Resource considerations |

|

| What would patients and their doctors think about this intervention |

|

|

Differences between this summary and other sources |

|

| Could this evidence change in the future? |

|

How we conducted this summary

Using automated and collaborative means, we compiled all the relevant evidence for the question of interest and we present it as a matrix of evidence.

Follow the link to access the interactive version: Ibuprofen versus acetazolamide in acute mountain sickness.

Notes

The upper portion of the matrix of evidence will display a warning of “new evidence” if new systematic reviews are published after the publication of this summary. Even though the project considers the periodical update of these summaries, users are invited to comment in Medwave or to contact the authors through email if they find new evidence and the summary should be updated earlier.

After creating an account in Epistemonikos, users will be able to save the matrixes and to receive automated notifications any time new evidence potentially relevant for the question appears.

This article is part of the Epistemonikos Evidence Synthesis project. It is elaborated with a pre-established methodology, following rigorous methodological standards and internal peer review process. Each of these articles corresponds to a summary, denominated FRISBEE (Friendly Summary of Body of Evidence using Epistemonikos), whose main objective is to synthesize the body of evidence for a specific question, with a friendly format to clinical professionals. Its main resources are based on the evidence matrix of Epistemonikos and analysis of results using GRADE methodology. Further details of the methods for developing this FRISBEE are described here (http://dx.doi.org/10.5867/medwave.2014.06.5997)

Epistemonikos foundation is a non-for-profit organization aiming to bring information closer to health decision-makers with technology. Its main development is Epistemonikos database (www.epistemonikos.org).

Potential conflicts of interest

The authors do not have relevant interests to declare.