Epistemonikos summaries

← vista completaPublished on June 18, 2020 | http://doi.org/10.5867/medwave.2020.05.7746

Reminder sent by mail to increase adherence to influenza vaccination

Recordatorio enviado por correo postal para aumentar adherencia a vacunación contra influenza

Abstract

INTRODUCTION Different interventions have been proposed to improve influenza vaccine coverage. The use of reminders, through letters, phone calls, pamphlets or technological applications, among others, has stood out among the different alternatives to increase adherence to vaccination. However, its effectiveness is not clear. In this summary, the first of a series of evaluation of reminders will address the use of a reminder sent by mail.

METHODS We searched in Epistemonikos, the largest database of systematic reviews in health, which is maintained by screening multiple information sources, including MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane, among others. We extracted data from the identified reviews, analyzed the data from the primary studies, performed a meta-analysis and prepared a summary table of the results using the GRADE method.

RESULTS AND CONCLUSIONS We identified eight systematic reviews that included 35 primary studies, of which 32 correspond to randomized trials. We concluded that a reminder sent by mail, probably increase adherence to influenza vaccination in all age groups (adult population, over 60 an under 18)

Problem

Influenza is an acute respiratory disease caused by the influenza virus that can be prevented with a seasonal vaccine. Despite this, it remains an important cause of morbidity and mortality[1] since it is estimated that annual influenza epidemics cause 3-5 million serious cases and 290,000 to 650,000 deaths[2]. Additionally, these are associated to school and work absenteeism, generating substantial productivity losses[2].Various interventions have been proposed to increase the use of the influenza vaccine. Reminders can be provided through different communication channels: letters, phone calls, pamphlet or technological applications, among others. This article is part of a series evaluating the use of reminders and will focus particularly on sending, via traditional mail, a letter, postcard or brochure type reminder.

Methods

We search in Epistemonikos, the largest database of systematic health reviews, which is maintained through searches in multiple sources of information, including MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane, among others. We extracted the data from the identified reviews and analyzed the data from the primary studies. With this information, we generate a structured summary called FRISBEE (Friendly Summaries of Body of Evidence using Epistemonikos), following a pre-established format, which includes key messages, a summary of the set of evidence (presented as an evidence matrix in Epistemonikos), meta-analysis of the total of the studies when possible, a summary table of results with GRADE method and a section of other considerations for decision making.

|

Key messages

|

About the body of evidence for this question

|

What is the evidence. |

We found eight systematic reviews[3],[4],[5],[6],[7],[8],[9], [10] which included 35 primary studies in 34 references [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34], [35], [36], [37], [38], [39], [40], [41], [42], [43], [44] of which, 32 are randomized trials reported in 31 references [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34], [35], [36], [37], [38], [39], [40], [41]. Five trials were excluded [16], [18], [21], [33], [35] because they included co-interventions to increase influenza vaccination. Two trials were excluded [19], [24] because the intervention consisted of two or more letters as a reminder.In addition, observational studies [42], [43], [44] did not increase the certainty of existing evidence, nor did they provide additional relevant information. Finally, this table and the summary in general are based on 25 trialsreported in 24 references [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [17], [20], [22], [23], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [34], [36], [37], [38], [39], [40], [41]. |

|

What types of patients were included* |

The trials included a total of 589,144 participants of all ages, including children over six months to adults over 65 years. All included participants were targeted from population at risk, with the exception of two trials, targeted to the general population [23], and to the beneficiaries of a health insurance [28]. Five trials included children [19], [22], [24], [25], [41], 14 trials included older adults (over 60 years old) [11], [12], [13], [15], [17], [20], [27], [29], [32], [31], [34], [37], [38], [39] and the rest of the trials included population of any age. In general, the trials excluded participants who had already received the vaccine prior to the start of the trial, with egg allergy or participants living in nursing homes. |

|

What types of interventions were included* |

All trials evaluated the use of mail reminders in the form of postcard [11], [12], [13], [15], [20], [26], [27], [34], [36], letter [14], [17], [22], [23], [25], [28], [29], [31], [37], [38], [39], [40], [41] or pamphlet [30], [31]. All included trials compared against usual medical care. |

|

What types of outcomes |

The systematic reviews identified only evaluated adherence to treatment (influenza vaccination rate) The average follow-up of the trials was five months and 12 days (range from two weeks to 12 months). |

* Information about primary studies is not extracted directly from primary studies but from identified systematic reviews, unless otherwise stated.

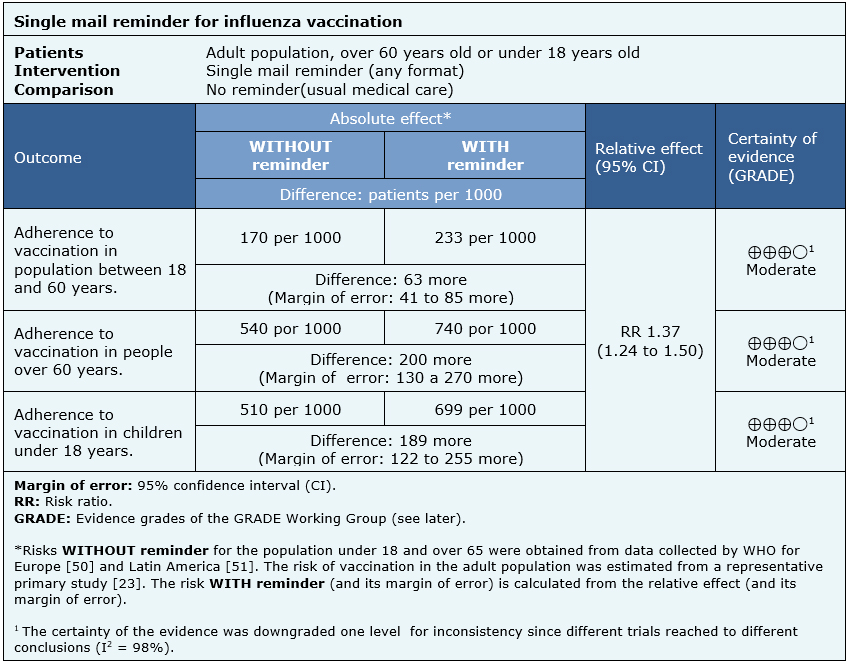

Summary of findings

The information on the effects of a single mail reminder is based on 25 randomized trials that included 589,144 participants [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [17], [20], [22], [23], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [34], [36], [37], [38], [39], [40], [41].

All trials reported the outcome adherence to vaccination.

The summary of findings is as follows:

- A single mail reminder probably increases adherence to influenza vaccination in a population between 18 and 65 years.

- A single mail reminder probably increases adherence to influenza vaccination in people over 60.

- A single mail reminder probably increases adherence to influenza vaccination in a population under 18.

| Follow the link to access the interactive version of this table (Interactive Summary of Findings – iSoF) |

Other considerations for decision-making

|

To whom this evidence does and does not apply |

|

| About the outcomes included in this summary |

|

| Balance between benefits and risks, and certainty of the evidence |

|

| Resource considerations |

|

| What would patients and their doctors think about this intervention |

|

|

Differences between this summary and other sources |

|

| Could this evidence change in the future? |

|

How we conducted this summary

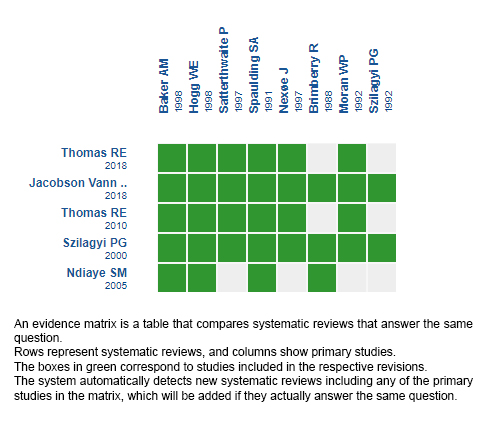

Using automated and collaborative means, we compiled all the relevant evidence for the question of interest and we present it as a matrix of evidence.

Follow the link to access the interactive version: Recordatorios mediante cartas paraaumentar la adherencia a la vacunación contra la influenza en población general

Notes

The upper portion of the matrix of evidence will display a warning of “new evidence” if new systematic reviews are published after the publication of this summary. Even though the project considers the periodical update of these summaries, users are invited to comment in Medwave or to contact the authors through email if they find new evidence and the summary should be updated earlier.

After creating an account in Epistemonikos, users will be able to save the matrixes and to receive automated notifications any time new evidence potentially relevant for the question appears.

This article is part of the Epistemonikos Evidence Synthesis project. It is elaborated with a pre-established methodology, following rigorous methodological standards and internal peer review process. Each of these articles corresponds to a summary, denominated FRISBEE (Friendly Summary of Body of Evidence using Epistemonikos), whose main objective is to synthesize the body of evidence for a specific question, with a friendly format to clinical professionals. Its main resources are based on the evidence matrix of Epistemonikos and analysis of results using GRADE methodology. Further details of the methods for developing this FRISBEE are described here (http://dx.doi.org/10.5867/medwave.2014.06.5997)

Epistemonikos foundation is a non-for-profit organization aiming to bring information closer to health decision-makers with technology. Its main development is Epistemonikos database (www.epistemonikos.org).

Potential conflicts of interest

The authors do not have relevant interests to declare.