Resúmenes Epistemonikos

← vista completaPublicado el 31 de enero de 2022 | http://doi.org/10.5867/medwave.2022.01.002146

Adición de ejercicio aeróbico a monoterapia de fármacos con efecto antidepresivo para la terapia de trastorno depresivo mayor en adultos

Addition of aerobic exercise to antidepressant drug monotherapy for major depressive disorder in adults

Abstract

Introduction Major depressive disorder is frequent and implies a high morbimortality. The addition of exercise has been proposed to improve the response rate to pharmacological monotherapy. However, this intervention is still controversial.

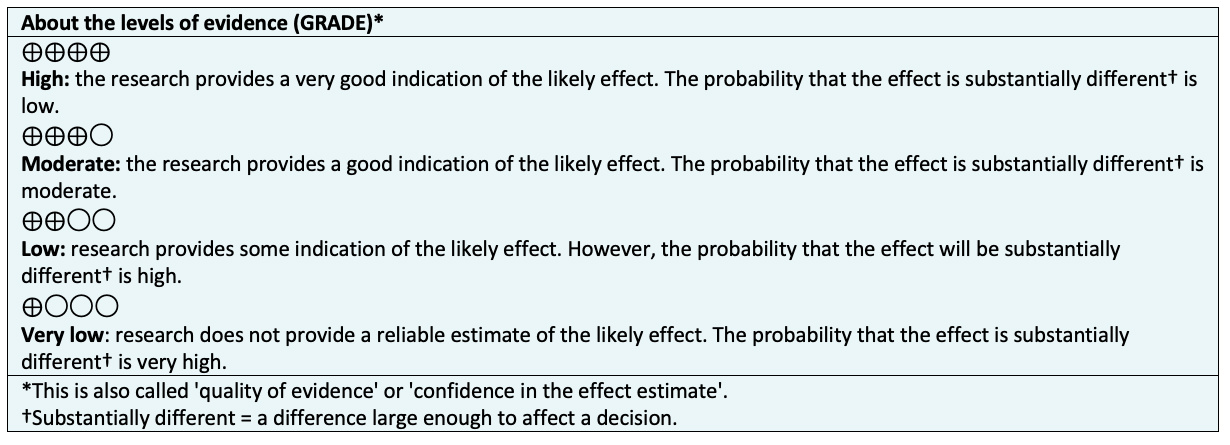

Methods We searched Epistemonikos, the largest database of systematic reviews in health, maintained by screening multiple sources of information, including MEDLINE/PubMed, EMBASE, and Cochrane. We extracted data from the identified reviews, analyzed the data from the primary studies, performed a meta-analysis, and prepared a summary table of the results using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) method.

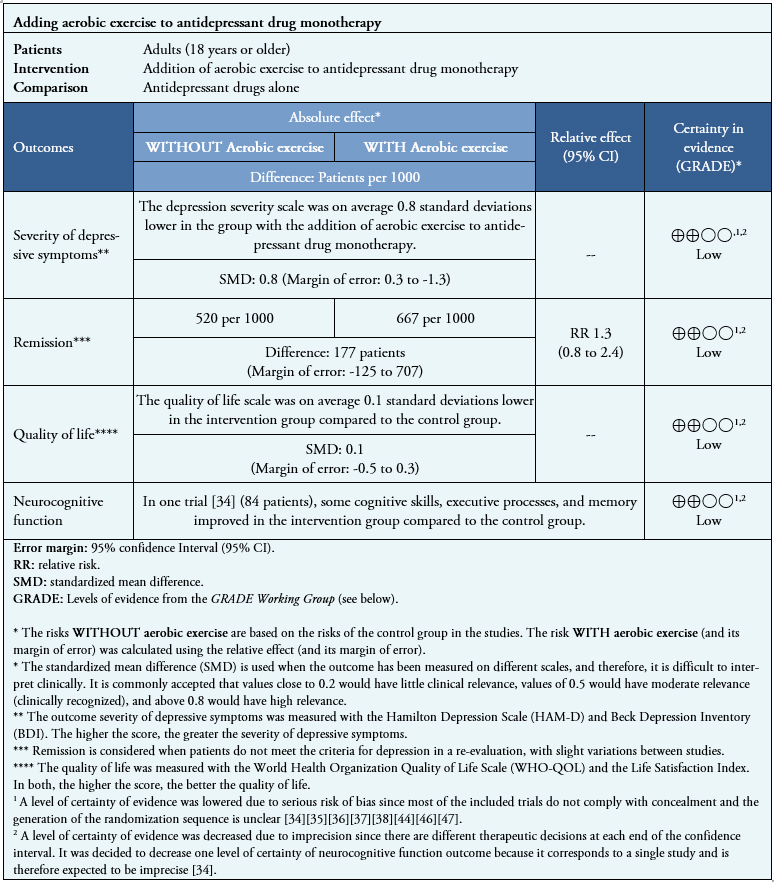

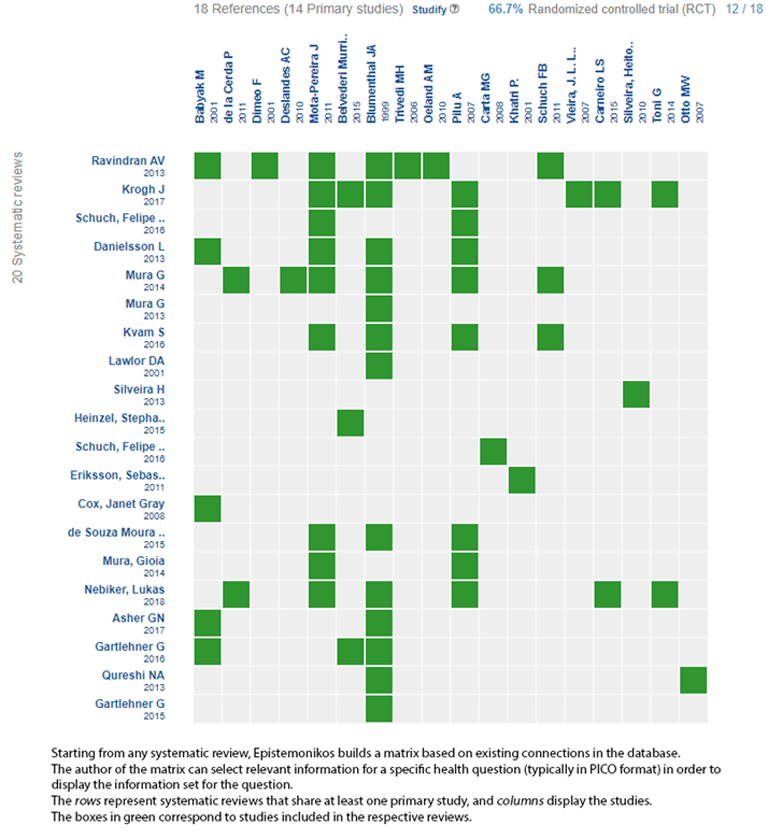

Results and conclusions We identified 20 systematic reviews that together included 15 primary studies. Of these, eight were randomized trials. We con-clude that the addition of aerobic exercise to pharmacological monotherapy for patients with major depression could slightly decrease the severity of depressive symptoms with low certainty of evidence.

Problem

Depressive disorder is a psychiatric pathology that currently affects 264 million people worldwide. It is associated with disability, other comorbidities and, in severe cases, can lead to suicide [1]. The first line of pharmacological treatment for patients with depression is serotonin reuptake inhibitors, but only 28-33% of patients achieve remission. This means that about two-thirds of patients with depression require other antidepressants or combinations of drug families [2],[3], adding higher costs and more adverse effects [4].

This problem encouraged the study and development of combination therapy strategies. This approach consists of combining two or more therapies with consolidated antidepressant action (adjuvant) and adding a therapy with unknown antidepressant effect to a known antidepressant (enhancer) [5]. There are pharmacological and non-pharmacological enhancers, including aerobic exercise, among the most relevant and widely studied strategies. Aerobic exercise decrease stress hormones (epinephrine and cortisol) [6], modulates norepinephrine, dopamine, and serotonin levels [7]. Moreover, it is beneficial for many organic diseases (e.g., diabetes, hypertension, coronary heart disease) and improves self-concept and confidence. In addition, few adverse effects have been reported [8],[9]. However, there are inconclusive results on the effectiveness, prescription mode, and safety of physical exercise for treating depressive disorder.

Methods

We searched Epistemonikos – the largest database of systematic reviews in health – which gathers information from multiple sources, including MEDLINE/PubMed, EMBASE, and Cochrane. We extracted data from the identified reviews and analyzed the primary studies (Table 1). We generated a structured summary called FRISBEE (Friendly Summaries of Body of Evidence using Epistemonikos) with this information. Following a pre-established format, we included main messages, a summary of the body of evidence (presented as an evidence matrix in Epistemonikos), a meta-analysis of all studies, if possible, a summary table of results with the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) method, and a section of other considerations for decision-making. (Tables 2, and *)

|

Key messages

|

About the body of evidence for this question

|

What is the evidence. |

We found 20 systematic reviews [10],[11],[12],[13],[14],[15],[16],[17],[18],[19],[20],[21],[22],[23],[24],[25],[26],[27],[28],[29] that which included 14 primary studies in 18 references [30],[31],[32],[33],[34],[35],[36],[37],[38],[39],[40],[41],[42],[43],[44],[45],[46],[47], of which eight are randomized trials in 12 references [34],[35],[36],[37],[38],[40],[41],[42],[43],[44],[45],[46],[47]. This table and this summary are based on the latter, since the observational studies did not increase the certainty of the existing evidence, nor did they provide relevant information. One randomized trial [42] could not be included in the meta-analysis, as the necessary data were not reported within the systematic reviews. |

|

What type of patients did the studies include? * |

Five trials incorporated patients with a major depressive disorder according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV criteria [36],[37],[38],[44],[47]. One trial used the International Classification of Diseases, 10th edition criteria for depression [36], and one trial included patients with a score equal to or greater than 18 on the 17-item Hamilton Depression Scale [46]. One trial included hospitalized patients with severe depression [38], and two trials included treatment-resistant patients [37],[44]. One trial analyzed patients with mild to moderate depression [35]. One trial, extracting information directly from the primary study, incorporated patients with moderate depression [36]. The remaining three trials do not report severity as a diagnostic criterion [36],[46],[47]. Three trials included only female patients [36],[37],[47], while the other four trials included both sexes. [35],[38],[44],[47]. Regarding population age among trials, patients older than 50 years [35], between 40 and 60 years of age [37], between 18 and 65 years [36], and 18 to 60 years [44] were included. Of note, it was necessary to extract information directly from the primary study for three trials. These trials included patients aged 18 to 60 years [38], between 65 and 85 years [46], and another trial that included patients with a mean age of 43.66 years [47]. |

|

What type of interventions did the studies include? * |

Regarding the intervention, all trials evaluated the addition of aerobic exercise to drugs. Three trials evaluated aerobic exercise plus antidepressant drugs versus antidepressants alone from different pharmacological families [37],[38],[44], and two trials compared against a specific antidepressant (sertraline) [35],[46]. We extracted information from the primary study for two trials that compared against the standard treatment, where 100% of participants were on antidepressant therapy of any type. One trial reported that the most frequently used serotonin reuptake inhibitor antidepressant was fluoxetine (66.7%), followed by escitalopram (22.2%) [35]. Another trial reported that the control and intervention groups used serotonin reuptake inhibitors (fluoxetine and paroxetine) and nonselective monoamine inhibitors (imipramine, amitriptyline, clomipramine) equally [47]. Regarding intervention fidelity, in five trials, aerobic exercise was performed in a supervised manner [35],[36],[37],[38],[47], and in one trial, only one weekly session was supervised [44]. Primary study data was extracted for one trial, where the exercise was supervised [46]. Regarding the delivery strategy of the intervention, three trials conducted aerobic exercise sessions in a group setting [35],[37],[46], while the other four trials conducted individual training [36],[37],[38],[44],[47]. In terms of training frequency, four trials had aerobic exercise sessions three times per week [35],[36],[38],[47], two trials had a frequency of twice a week [37],[47], and one trial had a frequency of five times per week [44]. In terms of training time, two trials used 45-minute aerobic exercise sessions [35],[36], and two trials had 60-minute sessions [37],[46], and in another, the training session was 30 to 40 minutes in duration [44]. We also extracted information directly from two trials. One trial had sessions of 50 minutes [4], while the other did not report a defined duration for the sessions and stated that patients should complete 16 kilocalories per kilogram per week [38]. In terms of assessing the cardiovascular response to exercise, three trials established a threshold for heart rate during physical activity as 70 to 80%, 65 to 75%, and from 60% of maximum heart rate [35],[36],[46], respectively. In the remaining four trials, no limiting heart rate was reported [37],[38],[44],[47]. In two trials, patients could choose the exercise. The options were cycling, walking, and jogging [35], or stationary bicycle, treadmill, and elliptical [38]. While in the remaining five trials, the choice of aerobic exercise modality was not reported [36],[37],[44],[46],[47]. One trial based the exercise on cardio-fitness [37], one trial on walking [44], another trial on cycling [46], and finally, one trial on water aerobic exercise [47]. With information extracted directly from the primary study, one trial included traditional games, exercise circuits, jumping rope, exercise balls, brisk walking, and dancing as aerobic activity [36]. |

|

What type of outcomes did they measure |

The trials reported multiple outcomes, which were grouped by the systematic reviews as follows:

Only the first four outcomes mentioned above were contemplated and analyzed within this FRISBEE. The average follow-up of the trials was 18 weeks, with a range between 12 and 40 weeks. |

*Information on primary studies is extracted from the identified systematic reviews, not directly from the studies unless otherwise specified.

Summary of results

Information on the effects of adding exercise to monotherapy with antidepressant drugs is based on eight randomized trials involving 346 patients.

Seven trials measured severity of depressive symptoms (346 patients) [35],[36],[37],[38],[44],[46],[47], three trials measured remission (253 patients) [35],[44],[46] and two trials measured quality of life (133 patients) [35],[37]. Regarding neurocognitive functions, no review allowed data extraction in a way that could be incorporated into a meta-analysis, so information on that outcome is presented as a narrative synthesis based on one trial (84 patients) [34].

No trials evaluated adverse effects, social isolation, or occupational functioning.

The summary of results is as follows:

- The addition of aerobic exercise may slightly decrease the severity of depressive symptoms (low certainty of evidence).

- The addition of aerobic exercise could result in little or no difference in disease remission and quality of life (low certainty of evidence).

- The addition of aerobic exercise may slightly increase neurocognitive function (low certainty of evidence).

- The evidence reviewed did not report "severe adverse effects", "social isolation", or "occupational functionality".

See Table 2

Table 2. Summary of findings

Follow the link to access the interactive version of this table (Interactive Summary of Findings - iSoF)

Other considerations for decision-making

| To whom this evidence applies and to whom it does not apply. |

|

|

About the outcomes included in this summary |

|

|

Harm/benefit balance and certainty in evidence |

|

|

Resource considerations |

|

|

What would patients and their doctors think about this intervention |

|

|

Differences between this summary and other sources |

|

|

Could this information change in the future? |

|

How we conducted this summary

Using automated and collaborative means, we compiled all the relevant evidence for the question of interest and we present it as a matrix of evidence.

Follow the link to access the interactive version: Addition of aerobic exercise to antidepressant drug monotherapy for major depressive disorder in adults

Notes

The upper portion of the matrix of evidence will display a warning of “new evidence” if new systematic reviews are published after the publication of this summary. Even though the project considers the periodical update of these summaries, users are invited to comment in Medwave or to contact the authors through email if they find new evidence and the summary should be updated earlier.

After creating an account in Epistemonikos, users will be able to save the matrixes and to receive automated notifications any time new evidence potentially relevant for the question appears.

This article is part of the Epistemonikos Evidence Synthesis project. It is elaborated with a pre-established methodology, following rigorous methodological standards and internal peer review process. Each of these articles corresponds to a summary, denominated FRISBEE (Friendly Summary of Body of Evidence using Epistemonikos), whose main objective is to synthesize the body of evidence for a specific question, with a friendly format to clinical professionals. Its main resources are based on the evidence matrix of Epistemonikos and analysis of results using GRADE methodology. Further details of the methods for developing this FRISBEE are described here (http://dx.doi.org/10.5867/medwave.2014.06.5997)

Epistemonikos foundation is a non-for-profit organization aiming to bring information closer to health decision-makers with technology. Its main development is Epistemonikos database

Contributor roles

CSP: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, research, resources, data curation, writing - first draft, writing - revision and editing, visualization, and project management. CC: conceptualization, validation, formal analysis, writing - review and editing, visualization, and oversight.

Ethics

Due to the nature of this study, it was not submitted to an ethics committee.

Competing interests

]The authors declare no conflicts of interest with the subject matter.

Data sharing statement

The database of this study is available upon request.

Funding

This work did not receive any type of funding.

Acknowledgments

To the Catholic University Evidence Center and its collaborators.

Language of submission

Spanish.