Análisis

← vista completaPublicado el 4 de junio de 2024 | http://doi.org/10.5867/medwave.2024.05.2920

Análisis exploratorio sobre los mecanismos de pago a centros de salud mental comunitaria en Chile usando teoría fundamentada mixta

Exploratory analysis on payment mechanisms to Community Mental Health Centers in Chile using mixed grounded theory

Abstract

Introduction Research on psychiatric deinstitutionalization has neglected that reforms in this field are nested in a health system that has undergone financial reforms. This subordination could introduce incentives that are misaligned with new mental health policies. According to Chile’s National Mental Health Plan, this would be the case in the Community Mental Health Centers (CMHC). The goal is to understand how the CMHCpayment mechanism is a potential incentive for community mental health.

Methods A mixed quantitative-qualitative convergent study using grounded theory. We collected administrative production data between 2010 and 2020. Following the payment mechanism theory, we interviewed 25 payers, providers, and user experts. We integrated the results through selective coding. This article presents the relevant results of mixed selective integration.

Results Seven payment mechanisms implemented heterogeneously in the country’s CMHC are recognized. They respond to three schemes subject to rate limits and prospective public budget. They differ in the payment unit. They are associated with implementing the community mental health model negatively affecting users, the services provided, the human resources available, and the governance adopted. Governance, management, and payment unit conditions favoring the community mental health model are identified.

Conclusions A disjointed set of heterogeneously implemented payment schemes negatively affects the community mental health model. Formulating an explicit financing policy for mental health that is complementary to existing policies is necessary and possible.

Main messages

- Provider payment mechanisms could introduce incentives that are misaligned with community mental health, which has not been studied.

- This study can contribute to the design and evaluation of payment mechanisms following public policies.

- As a limitation, access to financial data was lacking.

Introduction

The response of health systems for people with mental illness has evolved from asylum to community-based services. This process has been called deinstitutionalization reforms [1]. In Chile, the community mental health center is central to transforming the community mental health model [2]. National mental health plans point out that payment mechanisms for community mental health centers have been misaligned with the model of care by encouraging an individual intra-box response to the detriment of a recovery and social inclusion approach [3].

The payment mechanism is a contract that creates rules between patients, providers, and payers, introducing incentives [4]. These incentives influence all the constituent elements of the system: users, provision, drugs and technologies, human resources, governance, information systems, and financing [5].

The evidence about how the incentives of these mechanisms operate in the case of community mental health care is inconclusive. It is sometimes contradictory, and conceptual frameworks do not facilitate their interpretation [6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. Research on deinstitutionalization has neglected that reforms in this field have been nested in a more extensive healthcare system, which has also undergone reforms. Mental health reforms have utilized the financing mechanisms imposed on health systems [14]. This financial subordination could introduce incentives that are misaligned with the community mental health model.

This paper aims to understand how the payment mechanism to the community mental health center is a potential incentive for implementing the community mental health model in Chile. The country aims to triple the mental health budget, including an investment plan for community mental health centers, but it must be efficient in its incentives. This study can contribute to designing and evaluating payment mechanisms following public policies.

Methods

This is an exploratory mixed quantitative-qualitative convergent type study [15] using grounded theory [16]. The Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine of the University of Chile approved this work.

The quantitative component corresponds to secondary data from public administrative statistics from the Department of Health Statistics and Information of the Chilean Ministry of Health between 2010 and 2020, from public insurance (Fondo Nacional de Salud) and the National Institute of Statistics.

The data were analyzed using descriptive summary measures obtaining the absolute and relative frequency of community mental health centers in force, dependency, and location; population attended (admissions, discharges, under control, diagnoses, sex, age); and interventions provided (individual, intra-center group, extra-center group, professional who provides it).

During the data collection process, data quality problems were observed, so the information from the centers that showed completeness for the period analyzed was used for convenience. This affects the study, limiting the representativeness of the centers. For this reason, it was decided that, for each result, the number of centers considered in each analysis should be detailed due to their data completeness from 2010 to 2020. This is a way of transparentizing the risk of registration bias that limits this exploration.

The qualitative component includes data from interviews with 25 people, subject to informed consent (Table 1). Using theoretical sampling, the inclusion criteria represented the three roles in tension in a payment mechanism: payer, provider, and user. In practice, it includes representatives of user organizations, directors of community mental health centers, and institutional referents who decide on budget allocation (National Health Fund, Ministry of Health and Health Services). Representatives from different geographical areas were also included: north, center, south, and the metropolitan area.

Similarly, the Health Services included the criterion of having two health areas with and without a psychiatric hospital, which could be considered a factor of orientation toward the community model. It was also considered that women and men should be in each of the three groups. The sample limit was determined through content saturation. Although the sampling is theoretical and respects the methodology, it should be considered that groups underrepresented in the healthcare systems may be invisible in this exploration. Among these groups are people from indigenous areas, gender dissidences or ruralities, whose perspectives have acquired relevance in the response to mental health needs, and who require special attention.

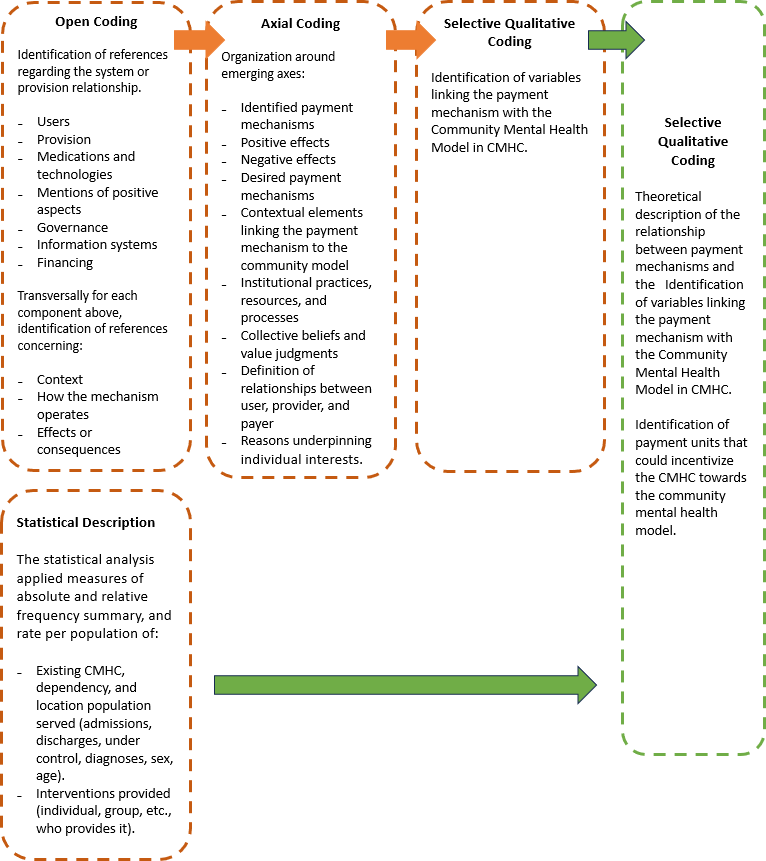

The interviews were recorded, transcribed with software support, and reviewed to ensure 100% ad verbatim. Interviewees were given access to their recordings and transcription. The textual analysis was subjected to open coding with the support of qualitative analysis software. The categories obtained referred to the relationship between payment mechanisms and each constituent element of a health system: users, provision of benefits, access to drugs and technologies, human resources, governance, information systems, and financing. For each category, subcategories were identified: the context in which the service is provided, how the payment mechanism operates, and the effects or consequences of the payment mechanism.

We then proceeded to establish relational conditions between the categories through the axial coding process, based on nine axes: payment mechanisms; positive effects of the payment mechanisms; negative effects; desired payment mechanisms; contextual elements that relate the payment mechanism to the community model; institutional practices, resources and processes involved; collective beliefs and value judgments involved; definition of the relationships between user, provider, and payer; and reasons underlying individual interests.

Likewise, the quantitative and qualitative results were integrated through selective coding around two dimensions:

-

The theoretical description of the relationship between payment mechanisms and the community mental health model in community mental health centers, for each constituent element of a health system.

-

The description of payment units that can incentivize the community mental health center towards the community mental health model.

The process of analysis of the results is summarized in Figure 1. This article presents the relevant aspects of the last analysis step, i.e., the mixed selective integration.

Outline of the process of analyzing the results using mixed grounded theory.

Source: Prepared by the authors of this study,

Results

The mental health policy in Chile establishes that one community mental health center is required for every 50,000 inhabitants. A total of 104 publicly funded community mental health centers were identified. A rate of 0.7 such centers per 100,000 beneficiaries of the National Health Fund was estimated for 2020. 86% of the Health Services have community mental health centers. Only 25% of the communes have one of these centers, but they correspond to 77% of the communes with more than 50,000 inhabitants.

Incentives to various components of the community mental health center

The interviewees recognize seven heterogeneously implemented payment mechanisms for community mental health centers, which have influenced various components of the organization. However, in practice, they respond to three mechanisms subject to rate and public budget limits prospectively, which differ in the payment unit.

The first mechanism is an annual budget that provides financial backing for a payroll. The second mechanism is a package of benefits associated with a diagnosis or condition per person. This second mechanism recognizes payments for diagnoses included in the universal access guarantee plan, a program of valued benefits until 2020, and various agreements with the intersector. These two mechanisms support the operation of community mental health centers. The third mechanism is competitive projects for community organizations with very limited amounts. There is consensus that the payment mechanisms are associated with implementing the community mental health model in these centers, discouraging it.

Interviewees point out that the community mental health model expects a payment mechanism to encourage the respective center to provide a wide range of interventions for all mental disorders and psychosocial risk factors; to have a mix of individual, group, on- and off-site care, with intersectoral interventions; interventions oriented towards comprehensive recovery and resolution, avoiding chronicity; evidence-based interventions; and articulation of shared care with other levels of care.

In 17 community mental health centers with available information, the rate of admissions per 1000 public insurance beneficiaries (National Health Fund) varied, increasing between 3.6 and 8.2 from 2010 to 2018. A similar proportion of women and men was estimated in 2018: 60% were adults between 20 and 64 years, 25% between 10 and 19, 10% were under 10 years, and 6% were over 65. The reasons were mood disorders (27%), usual childhood onset disorders (20%), disorders associated with drug use (19%), anxious disorders (15%), intrafamily violence (10%), schizophrenia (2%), and dementias (2%).

In 24 community mental health centers with available information, an average rate of population under control of 25 per 1000 NHF beneficiaries between 2010 and 2018 was estimated. Interviewees noted that if the government budget that funds community mental health centers is born from a disjointed set of heterogeneously implemented payment schemes, it incentivizes a selection of specific diagnoses that grant better funding. This occurs when this diagnosis is explicit in the payment mechanism, its tariff is higher, and the requirements for the provision of services are reduced to a few interventions, such as, for example, only medical consultation or the delivery of drugs.

When the institutional framework lacks an entity responsible for elaborating a mental health plan, the incentive of the payment mechanism to cover all the problems in this area is hindered. The payer has not taken responsibility for politically defining what it is willing to fund.

In 2020, 43 community mental health centers were under the Health Service (41%), 47 had municipal dependencies (45%), and 12 were administratively nested in a hospital (11.5%). Two community mental health centers describe a private, not-for-profit facility financed with public funds.

In the study, there is heterogeneity in community interventions, which vary partly due to the administrative dependence of each mental health center. Community interventions with territorial and user organizations are discretionary since these actions require organization outside the usual daytime hours, which implies an additional cost. Likewise, participation strategies in the mechanism are not encouraged. In 48 community mental health centers with available information, it was observed that between 2010 and 2016, about 85% of the activities were individual benefits within the center’s facilities. Between 2017 and 2018, it was 70%. Group benefits within the center barely represented between 2 and 3% of the benefits. Group activities outside the center representation, which until 2016 did not exceed 9% of the benefits, in 2017, bordered 25% of the total. In 2018, a rate of 6.4 benefits per person under control was estimated, with 4.3 corresponding to individual in-box benefits. Home visits are associated with the possibility of a vehicle to travel to the field. This is discretionary unless the budget explicitly determines it.

Concerning the incentive for integral recovery, resolvability, and avoidance of chronicity, when payment mechanisms condition access to a certain pharmacological arsenal, a chronification process occurs in community mental health centers. In 17 such centers with available information, it was estimated that the difference between the rate of admissions and discharges reached 5:1 in 2018. In 2019, the difference dropped to 4:1 due to the decrease in admissions in the last quarter, which was associated with the so-called "social outburst" (social and political crisis in Chile in October 2019).

Regarding evidence-based interventions, geographic and cultural diversity implies considering different worldviews regarding mental health, which is observed in rural areas and among indigenous peoples. It also implies considering the diversity of meanings of "community". In this context, it is described that the payer is unaware that mental disorders require shared and continuous care since payment mechanisms have restricted this possibility. In 48 community mental health centers with available information, it was estimated that between 2010 and 2019, consultancies with primary care represented a low proportion. This even decreased over the years from 1.8% in 2010 to 0.3% of services in 2019.

Similarly, it is pointed out that payment for consultancy should not be restricted to the psychiatrist. Crisis intervention or patient follow-up must be explicitly incorporated, as they are not implemented. The "social outburst" in 2019 and the COVID-19 pandemic are contexts that decreased care in community mental health centers. In fact, in 17 of them with available information, it was estimated that the admissions rate per 1000 beneficiaries declined from 8.2 in 2018 to 7.2 in 2019 and 4.2 in 2020.

In turn, it was detected that there is a favorable relationship with access to medicines and technologies. Respondents noted that there has been an incentive to have an essential psychopharmacological arsenal. The payment mechanism must be considered when a drug not included in the arsenal is required.

In another line, in the context of the pandemic, the incorporation of remote care using communications technologies in community mental health centers was accelerated, putting pressure on payment schemes to cover this type of care.

Regarding human resources, the model encourages teams to be oriented towards biopsychosocial services, integral recovery and autonomy of individuals, and territorial interventions. For those interviewed, the motivation and commitment of those working in community mental health centers allow them to function even with budgetary restrictions and payment schemes prioritizing individual consultations. This would be discouraged when working conditions and professional development are precarious. The consequence is abandoning a comprehensive approach in professional orientation, replacing it with an individual clinical approach, and disarticulating from the national mental health care plan and social inclusion. As a result, the judgment emerges that clinical work is becoming an executive process, but indolent with the users and ineffective, given the payment schemes prioritizing individual consultation.

In addition, there is heterogeneity in the forms of contracting in community mental health centers, particularly due to the diversity of the administrative dependence of these centers. Thus, in 48 of them with available information, it was estimated that more than half of the individual activities are carried out by a psychologist (66.7% of services in 2010 to 50% in 2020). Individual services provided by a social worker have been around 15 and 16%. Individual benefits from occupational therapists increased from 9.3% in 2010 to 12.9% in 2019. Individual benefits by nurses ranged from 2.8% to 4.4%. Checkups performed by nursing technicians varied, peaking at 3.1% in 2011 to none recorded in 2015. Since 2017, substance use disorders that nurse technicians check have bordered 8% of total individual benefits. Regarding family and group psychotherapy, more than 96% of the time is performed by a psychologist.

According to providers and users, incorporating peer-workers is a key factor in the community mental health model. It was observed that in 2017, the administrative record of individual benefits performed by a "community manager" was incorporated. These benefits had the lowest proportion of those performed by various team members, reaching 0.25% of individual benefits in 2020. This funds self-help groups conducted by community workers, although heterogeneously in community mental health centers. The incorporation of community workers would have the potential to introduce horizontal power relations with users.

Concerning users, interviewees point out that the community mental health model expects a payment mechanism to incentivize adherence and participation in treatment. The social determination of mental illnesses strains the possibility of covering effective, comprehensive treatments. This implies considering that payment schemes need to introduce risk factors for differentiated population needs. When the payment mechanism does not consider the subsidy to the person’s transportation, it becomes a geographical barrier, causing abandonment of treatments or partial treatments. The limitation of opening hours is also relevant.

Regarding governance, for those interviewed, the community mental health model expects a payment mechanism to be consistent with encouraging users' participation in managing the community mental health center. An instrumental relationship between the provider and payer with civil society organizations prevents them from having the power to influence decision-making on mental health financing. This would be related to the level of ignorance, stigma, prejudice, and discrimination of users, even within the health system organization itself. In a selection of 48 community mental health centers, it was estimated that about 2% of group activities were recorded as work with social organizations of users and family members between 2017 and 2020. Regarding articulation with intersectoral institutions in the assigned territory, it was estimated that intersectoral work was the most frequently recorded activity among the group services performed outside the community mental health center facilities, reaching over 90% in 2016. However, it decreased to about 20% in 2018 when the recording of group psychosocial intervention was incorporated, which is ambiguously defined. Along these lines, it is proposed that community mental health centers are responsible for linking with the assigned territory. Likewise, territorial activities and means of transportation for the safe transfer of personnel should be explicitly financed.

Regarding information systems, community mental health centers mainly record individual consultations since the registration systems prioritize this. Hence, it is important to approach the units in charge of statistics so that they understand the nature of the activities of community mental health centers, along with training their staff in the community mental health model. At the same time, it was noted that there have been no processes for designing and implementing information systems for the community mental health model. Nor, according to those interviewed, is there any dialogue between the various information systems that coexist in the health sector.

Regarding financing, the community mental health model expects a payment mechanism consistent with the incentive of efficient use of resources, the sustainability of the community mental health center, and the coherent objectives stated in the mental health policy. For the interviewees, heterogeneity in the type of leadership of the centers would be associated with the incentive for efficiency. Community mental health centers end up assuming the financial risk because the payer has not assumed its responsibility to respond to the population’s increased demand for care. This is interpreted to mean that public insurance is the only one that does not lose with the current payment mechanisms. Similarly, there is a perception that the forms of administration of community mental health centers keep them disempowered in decision-making about resources. Consequently, there is a baseline problem of lack of discussion about a policy for funding community mental health centers and about who takes responsibility for the governance of the funding system for community mental health centers.

Unity of payment mechanisms in favor of the community-based model

For interviewees, achieving consistency between the community mental health model in ad hoc centers and the incentives of their payment mechanism is more complex than simply deciding on the payment unit.

From a governance standpoint, the payment mechanism would relate in favor of the community mental health model when:

-

An articulated set of payment schemes is implemented under a financing policy consistent with the mental health policy.

-

It defines responsible parties for the purchasing function and the forms of participation of the payer, provider and user.

-

The administrative dependence of the community mental health centers grants conditions of autonomy in management.

-

They incorporate and implement objectives and strategies on mental health stigma.

-

Mechanisms are established for user participation in managing the community mental health center.

-

An intersectoral mental health policy is established with multisectoral budget allocation and management procedures.

From the point of view of the strategic management of community mental health centers, the payment mechanism would be related in favor of the community mental health model when:

-

Recruitment, induction, training, and supervision of staff are explicit and monitored.

-

Peer-workers are incorporated as part of the teams.

-

Information systems that report on productive capacity and quality are optimized.

-

Extended opening hours are organized.

-

The financing plan is widely communicated.

From the point of view of the payment unit, the mix of schemes seems more appropriate for payment mechanisms to be related in favor of the community mental health model. Some units that account for incentives were more clearly identified as possible to address through a payment mechanism to the community mental health center (Table 2).

Discussion

The payment mechanisms identified are recognized in classic classification systems [4] and in recent European projects evaluating mental health services [17]. An institutional financing system for community mental health centers is not recognized, which contradicts their critical priority in mental health policies and the relevance of having an explicit mental health financing policy [3]. This relates to a weakened purchasing function in the case of mental health, which is crucial when resources are limited [18]. This is Chile’s first exploration of payment mechanisms for community mental health centers.

For providers and users, community participation seems to be encouraged by technical guidelines [19], staff effort [20], and the influence of social organizations rather than by current payment mechanisms. Studies evaluating mental health services have warned about problems in the investigation of financial aspects, such as the disambiguation of the terminology used for mental health services [21] and the estimation of their costs [22].

This study adds a new dimension to the problems in this field by addressing payment rules perceived as incentives. The contextual elements that relate payment mechanisms to the community mental health model found in this study confirm that the financing of community mental health centers in Chile has been subordinated to the overall financing structure of the health system that has undergone reforms. The same system is currently undergoing a debate on a new reform to guarantee universal access. The payment mechanisms used for community mental health centers have not arisen from the analysis of suitability or coherence with the community mental health model but have responded to the instruments available for the entire health system. Although there is recognition that these centers have been implemented thanks to the allocation of the public budget, there are negative effects of the payment mechanisms used, which respond to disjointed schemes and heterogeneous implementation. The challenge is to ensure that the user, provider, and payer can do the right thing without this leading to an unfavorable outcome for any of them [23].

Universal access health care reforms may be an opportunity to push for greater coherence of health policies on mental health and the financing systems of the health systems themselves. However, this entails recognizing essential changes in the concept of mental health and mental illness, as well as the introduction of specific financing regulations for mental health services [14].

Conclusions

This is Chile’s first study on payment mechanisms for community mental health centers, and its exploratory nature contains limitations.

The study supports the previous concern of Chile’s National Mental Health Plan about the mismatch between the community mental health model and payment mechanisms. It also reinforces the need for further analysis of the consequences of this mismatch.

On the other hand, a disjointed set of heterogeneously implemented payment schemes negatively affects the community mental health model. Formulating a financing policy that articulates the mechanisms for community mental health centers complementary to mental health policies is necessary and possible, supporting the recommendation of having an explicit and transparent financing policy in the case of mental health. This contradicts the positions that propose that the general health financing system already contains it.

Contextual factors seem to play a key role in how payment mechanism incentives operate, and it is necessary to study how resources and services are distributed among different demographic and geographic groups, as well as to identify possible disparities in access and mental health outcomes.

Along these lines, it is essential to improve the quality of the administrative records that support financing, allowing for quantitative analyses that consider other factors such as population variation and demand for care, the expansion of the supply of services, among others.

Finally, the results of this study provide evidence that feeds back into policies to move in this direction. At the same time, it expands the possible dimensions that problematize the field of research on mental health financing.