Notas metodológicas

← vista completaPublicado el 23 de junio de 2025 | http://doi.org/10.5867/medwave.2025.05.3065

Generalidades sobre desarrollo y aplicación de conceptos clave para toma de decisiones informadas en salud

Overview on the development and application of the key concepts for decision-making in health care

Abstract

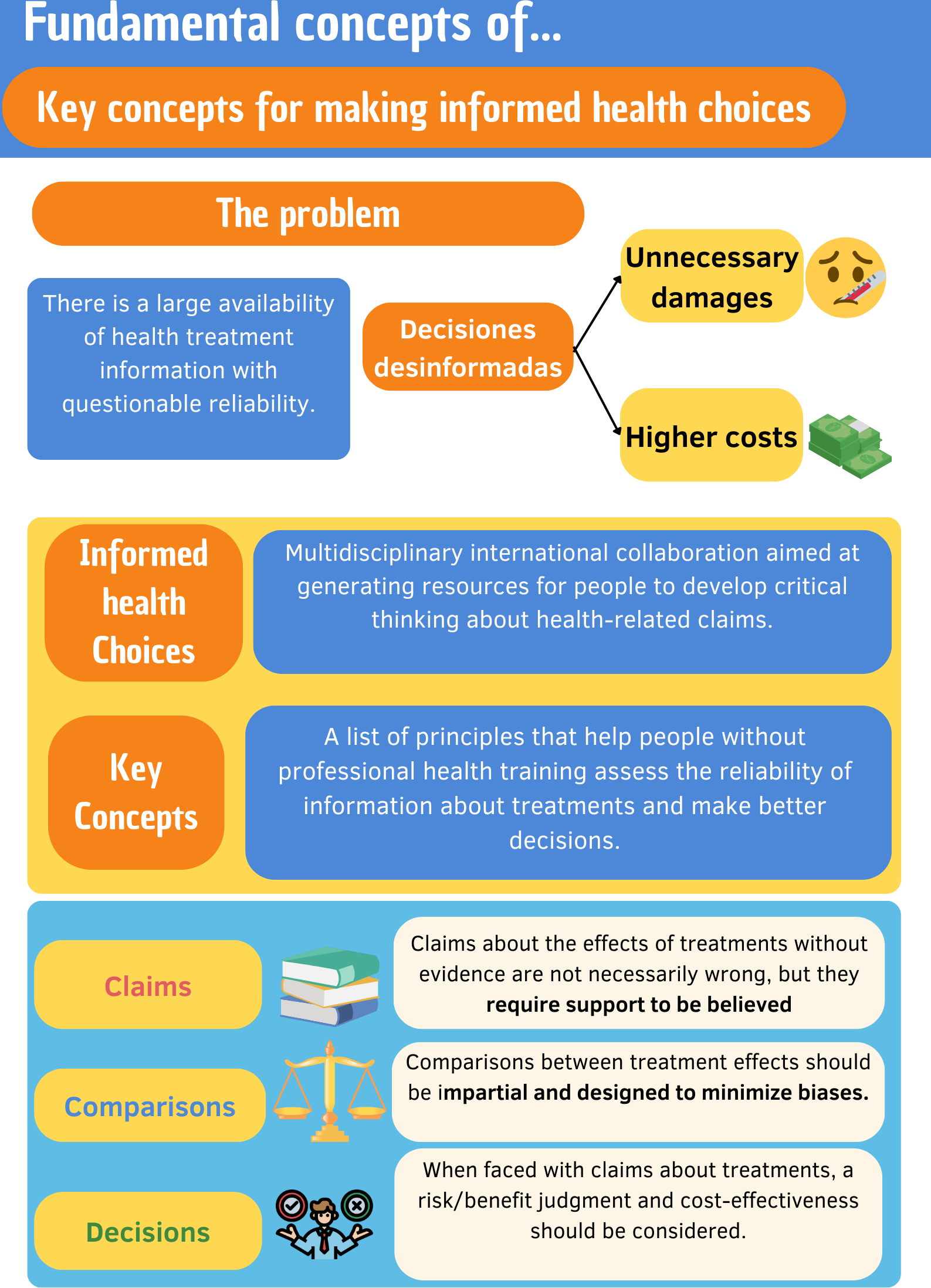

The volume of information about medical interventions has grown exponentially in recent decades. The increasing involvement of patients in decision-making creates a scenario in which they can constantly interact with multiple sources of information that can be correct, incorrect or misleading. In this context, promoting knowledge dissemination through reliable sources and fostering health literacy among the general population is crucial. The Informed Health Choices project aims to generate resources that can help individuals cultivate critical thinking about health interventions, thereby reducing unnecessary harm and financial costs. The Key Concepts of Informed Health Choices serve as the foundation for creating these resources. This is a list of principles potentially relevant for people without formal training in health topics to assess the reliability of the information about interventions. Resources based on these Key Concepts have been tested on primary and secondary school students in Africa, showing positive results in the short- and medium-term. This initiative is not free from limitations or considerations concerning its applicability but sheds light on how to face the new challenges that health education brings in times of . This article aims to contextualize the current scenario of health information and to introduce the Key Concepts for making informed health choices and the resources created based on them.The text is part of a methodological series on clinical epidemiology, biostatistics and research methodology conducted by the Evidence-based Medicine team at the School of Medicine of the University of Valparaíso, Chile.

Main messages

- There are multiple sources of information related to health interventions, which contain both valid and well-supported claims, as well as false claims or spurious interpretations.

- Critical thinking, associated with effective knowledge transfer, is crucial for shared decision-making about health interventions, as it enables stakeholders to evaluate the information they receive critically.

- Informed Health Choices is a multidisciplinary and international collaborative project to create relevant, accessible, and universal resources that facilitate the acquisition of critical thinking skills in the general population in order to inform health decisions.

- The key concepts for informed health choices consist of 49 principles organized into three main categories: statements, comparisons, and decisions. These concepts are designed to assess the reliability of health interventions critically.

Introduction

In healthcare and clinical decision-making, adherence to the recommendations is essential for the success of interventions on patients and requires strong support from the healthcare system [1]. However, in an increasingly vast context of information, an additional challenge presents itself. The plethora of messages that appear to be medical recommendations can confuse both clinicians and patients in a shared decision-making process [2]. This is why the evaluation and appropriate use of health information available on the Internet by patients has become crucial. In 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) coined the term "infodemia" [3,4,5] during the COVID-19 pandemic to refer to the massive volume of false or misleading information disseminated in print and broadcast/scientific communication media [4].

The highly abundant information available to patients is not only limited to that provided by experts and official sources of information dissemination but also to that delivered by unofficial media via social networks, television, print media, radio stations, and podcasts. Sometimes, many of these sources disseminate information based on studies of low methodological quality, with failures in translating knowledge and/or biased interpretations of scientific articles, which makes the current scenario even more confusing and complex [4,5,6].

Currently, patients play a central role in decision-making, combining the information they can obtain by their own means with their values and preferences [3,4,5]. In this context, health literacy — the acquisition of skills and competencies to seek, understand, evaluate, and use health-related information to make informed decisions — becomes relevant [4,7]. Greater health literacy is favorably associated with better health outcomes, as adherence to medical treatments and approaches is primarily influenced by the patient’s understanding of their disease and its management [7,8,9]. On the other hand, lack of health literacy has been consistently associated with negative outcome indicators, notably higher rates of hospitalizations, lower rates of influenza vaccination, poorer overall health status, and higher mortality in geriatric patients [9]. It has been estimated that making healthcare decisions based on insufficient information, primarily by patients with low health literacy and without prior consultation with a trained healthcare professional, has generated annual losses in healthcare systems. These losses amount to billions of dollars, which consequently result in a detriment to the quality of life of the population and even avoidable deaths [1,4,5,6,7,8,9,10].

Fostering critical judgment in patients and other stakeholders, as well as health literacy, is a challenge for healthcare workers, health systems, and educational systems at various levels [11,12]. In response to these challenges, several resources were created [6,13], including the DISCERN tool [14] and the books Smart Health Choices: Making Sense of Health Advice [15] and Know Your Chances: Understanding Health Statistics [16]. The problem with these resources lies in the fact that, despite proposing similar concepts, they use heterogeneous terminology, which makes it difficult to integrate their content. Moreover, they have not been systematically evaluated and tend to focus on specific concepts [6].

Faced with this scenario, the Informed Health Choices (IHC) initiative was born. Its initial objective is to create resources that enable the general population to evaluate claims about health interventions and develop critical judgments about them, guiding informed decision-making [4].

The Key Concepts for Making Informed Health Choices are one of the tools developed by Informed Health Choices and form the basis for developing educational resources to improve people’s ability to evaluate the effects of health interventions and thus make more informed decisions [6]. These concepts and the resources built on them have been initially implemented in resource-limited settings, especially in low-income countries, particularly in schoolchildren [4,6].

What is the Informed Health Decisions initiative?

Informed Health Decisions is an international collaboration of experts in research, medicine, epidemiology, communication, education, and design. It was created in response to the growing amount of health-related information of questionable reliability [2,4,5]. Its main objective is to develop resources that enable people to develop critical thinking about health claims, thereby facilitating shared and well-informed decision-making and seeking to avoid unnecessary harm and reduce health costs [4]. These resources have been primarily focused on children and adolescents, partly due to the greater difficulty in changing the behavior of adults [4,13,16].

On the other hand, the development of this initiative has led to the creation of the Informed Health Decisions network. This is an international and multidisciplinary network comprising experts in research methodology, health services, medicine, public health, epidemiology, design, education, communication, and journalism [17].

Currently, the Informed Health Decisions network partners with universities and nonprofit organizations in countries worldwide, including Australia, Chile, China, Greece, Kenya, Iran, Mexico, Norway, Rwanda, South Africa, Spain, Uganda, the United Kingdom, and the United States [18].

What are the key concepts for informed choices?

The Key Concepts for Informed Health Choices are a list of principles that can be meaningful for non-health professionals to understand. They are particularly relevant when assessing the reliability of certain information about a health intervention, especially when evaluating different alternatives or solutions [4,6,17].

Thus, the key concepts provide a tool to make a critical judgment of the information received, allowing the population:

-

Recognize when a valid source of information confirms the effects of a treatment.

-

Evaluate the reliability of evidence from comparative studies.

In turn, these principles serve as the underpinning for the development of educational resources that promote the understanding and application of the same concepts in the population, paving the way for self-care and community care [4,6,17].

Development of key concepts

The development of key concepts began in 2013 by Informed Health Decisions, with the intention of creating and evaluating resources to teach adults and children in low-income countries how to evaluate statements about health interventions. The creation of these principles was initially achieved through a systematic search for checklists of relevant concepts to inform critical judgments of claims written in the scientific literature. It also carried out others directed to the general public, emanating from journalists and health professionals. All these considered concepts related to the evaluation of the certainty of evidence [4,6,13].

This proposal included an advisory group consisting of researchers, journalists, professors, and other experts in health literacy, teaching, and the dissemination of evidence-based healthcare [6].

The first result of this project was achieved in 2015 with the publication of the first version of Key Concepts for Informed Health Decision Making [6]. This version comprises 32 concepts organized into six groups. Later, this version was revised and published in 2016, with 34 key concepts divided into three groups:

-

Affirmations.

-

Comparisons.

-

Decisions.

This taxonomy was constructed with the idea of simplifying the concepts for teaching them to elementary school children [4,6]. Although the list was not organized according to the complexity of understanding or application, nor in the order in which they should be learned, the authors have discussed it as something to be implemented in future explorations [4,6,13].

The most recent update of the list was made in 2022 and consists of 49 concepts organized in the same three groups as the previous version [4]. In this version, four subgroups were added to the domains of statements and comparisons and two subgroups to the domain of decisions to achieve a more orderly, transparent, and understandable material.

The list of concepts is constantly being evaluated and updated. Additionally, it is open to modifications, additions, or deletions of elements, which are reviewed annually by the Oslo Center for Informed Decisions [19].

Current list of key concepts for informed decisions in health.

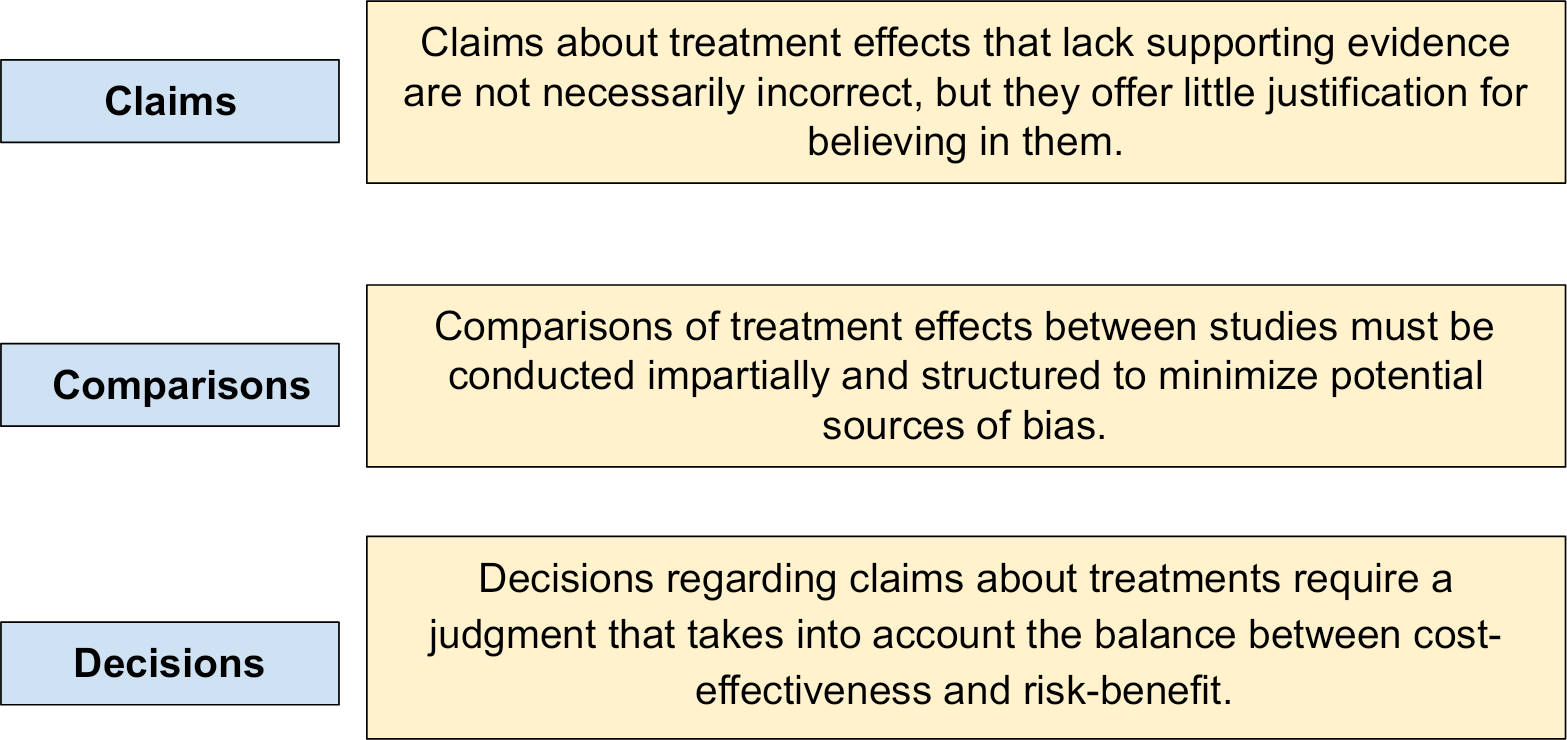

The list of key concepts 2022 [4] consists of 44 concepts grouped into three groups represented in Figure 1, which in turn are divided into different subgroups as shown below:

Claims (Table 1): claims about treatment effects that are not supported by evidence based on unbiased comparisons are not necessarily wrong; although there is little support for believing them. This group is further subdivided into four subgroups corresponding to the main domains. These are:

1.1. Assumption of safety or effectiveness of treatments may be misleading.

Main groups of key concepts.

1.2. Seemingly logical assumptions about research can be misleading.

1.3. Seemingly logical assumptions about treatments can be misleading.

1.4. Beliefs based on the source of a statement alone can be misleading.

Comparisons (Table 2): To identify treatment effects, studies must make unbiased comparisons. These, moreover, must be designed to minimize the risk of bias and random errors. This group is subdivided into four subgroups corresponding to the main domains:

2.1. Comparisons between treatments should be unbiased.

Concepts related to inter-treatment comparisons focus on distinguishing which comparisons are made in an unbiased and unbiased manner, and whether it is appropriate between treatments to compare.

Source: developed by authors from Oxman et al. [4].

2.2. Reviews of treatment effects should be unbiased.

2.3. Descriptions of effects should reflect the size of the effect.

2.4. Descriptions of effects should reflect the risk of making a random error.

Decisions (Table 3): what to do about treatment claims depends on a judgment about a problem. It also depends on the relevance of the available evidence, as well as the cost-effectiveness and risk/benefit balance. This group is subdivided into two subgroups corresponding to the main domains:

3.1. The evidence must be relevant.

The concepts associated with treatment decisions are based on evaluating the safety, consistency, and sustainability of the treatments to be applied.

Source: elaborated by authors based on Oxman et al. [4].

3.2. The expected advantages should outweigh the expected disadvantages.

Implementation of the key concepts in elementary school students

The Informed Health Decisions team has put the key concepts into practice by implementing resources generated based on these concepts. All this through five randomized clinical trials [20,21,22,23,24], of which three were conducted in Uganda [20,21,22], one in Rwanda [23] and one in Kenya [24]. The population studied were elementary school children in one study, secondary school students in three clinical trials and one meta-analysis [22,23,24,25], and adults in one study [21].

Between 2013 and 2015, the Informed Health Decisions team developed resources based on key concepts, utilizing ideas generated in-house. These resources were pilot-tested through non-participatory observation, interviews, and usability testing with teachers and students, as well as feedback from a network of teachers [20,21]. It was found that the original key concepts were too many to be taught in a single school semester. For this reason, 12 concepts were selected (Table 4) considering their importance, difficulty, and the information obtained in the piloting. The final result of this process was a textbook, a teacher’s guide, an exercise book, a poster, activity cards, and a song. All these resources were available in English and translated into Luganda and Swahili, the languages spoken in Uganda that were used to teach the concepts [20].

These materials were implemented in primary schools in Uganda. Two randomized clinical trials conducted by the Informed Health Decisions team [20,21] were carried out there. Their common objective was to evaluate the effect of teaching the key concepts to elementary school children [20] and their parents [21], respectively.

Between April and June 2016, 170 out of 2029 eligible primary schools in Uganda were randomly selected. Of these, 120 were recruited through a proportional random sample of randomly selected district lists stratified by location and school type (private or public) [20,21].

The objectives, methods, results, and conclusions of studies conducted in Uganda on elementary school children and their parents are synthesized below. The 1-year follow-up results of both studies are also presented [26,27].

Effects of the Informed Health Choices primary school intervention on the ability of children in Uganda to assess the reliability of claims about treatment effects: a cluster-randomized controlled trial.

This clinical trial aimed to evaluate the impact of an Informed Health Choices program on the ability of fifth-grade elementary school students in Uganda to assess claims about the effects of medical treatments. From previously selected schools, 10 183 fifth-grade primary school children aged 10-12 years were recruited [20]. These were randomly assigned to either the intervention (n = 60, comprising 76 teachers and 6383 children) or control (n = 60, comprising 67 teachers and 4430 children) groups. For the intervention group, teacher training was conducted, and educational resources were provided. Additionally, nine weekly classes were conducted over one school semester. These focused on 12 essential concepts for evaluating treatment effect statements and making informed decisions about health. Schools in the control group did not receive any intervention [20].

The primary outcome was the score on a validated questionnaire at the end of the semester, which consisted of two questions for each of the 12 concepts taught and had to be answered within one hour. In the intervention group, 69% achieved the minimum passing score, compared to 27% in the control group. After one year, the same questionnaire was administered again in both groups. The intervention group maintained a significant improvement in their skills, with 80.1% of the children achieving the minimum passing score compared to 51.5% in the control group [26].

The authors concluded that the use of Informed Health Decisions resources, combined with teacher training, was effective in enhancing children’s ability to evaluate treatment effect statements. This improvement was sustained for one year [20,26].

Effects of the Informed Health Choices podcast on the ability of parents of primary school children in Uganda to assess the trustworthiness of claims about treatment effects: one-year follow up of a randomized trial.

This study evaluated the effectiveness of a podcast from the Informed Health Choices team in improving the ability to critically analyze claims related to medical treatments in parents of children in the intervention group of the previously described clinical trial. A total of 675 participants were recruited. These were randomly assigned into two groups: one that listened to the podcast and one that only listened to media health public service announcements [21].

The results revealed that the group that listened to the podcast showed a significant improvement in evaluating treatment claims compared to the control group. Seventy-one percent of 288 parents in the intervention group scored at the predetermined minimum score for basic skills in assessing the reliability of treatment claims, while 38% of 273 parents in the control group achieved this score. A one-year follow-up was conducted by administering the same questionnaire one year after its initial application [21]. In the intervention group, 47.2% of 267 parents had a predetermined minimum score, while in the control group, 39.5% of 256 parents had it; the adjusted difference was 7.7%. The authors concluded that the podcast is effective in assessing treatment statements. However, this improvement dropped substantially after one year, indicating that constant practice of these skills is likely required to maintain them over time [21,27].

Implementation of key concepts in secondary school students

Two randomized clinical trials, published in 2023, were conducted in Uganda and Rwanda [28,29]. They were conducted to assess the critical thinking skills of secondary school students, aged 13-17 years, regarding health decision-making after receiving lessons on 9 of the 49 key concepts of Informed Health Decisions, which are considered a priority for critical thinking in health decision-making. To conduct the lessons, teachers received two days of training. In both studies, 10 lessons of 40 minutes were conducted during out-of-school hours to explain each of the nine concepts. The textbook, which translated key concepts into the respective languages of each country, was used for this purpose. Two weeks after the 10 classes were completed, a final multiple-choice assessment was administered to measure their ability to think critically based on the concepts taught, with a passing grade of 9 out of 18 correct answers. The intervention group received the lectures and took the test at the end of the lectures, while the control group took the final test without having received the lectures [28,29]. .

The study conducted in Uganda randomly selected 80 secondary schools, with 4743 students, 2477 students and 40 teachers in the intervention group, and 2376 students and 40 teachers in the control group. The results showed a 55% pass rate in the intervention group versus 25% in the control group. The authors concluded that the intervention, based on key concepts and utilizing resources created by the Informed Health Decisions team, was effective in improving the ability of secondary school students to think critically and make informed health decisions, targeting 9 of the 49 concepts [28].

The study, conducted in Rwanda, randomly selected 84 secondary schools across the country. A total of 3212 participants were recruited, with 1572 students and 42 teachers assigned to the intervention group and 1640 students and 42 teachers assigned to the control group. The results showed an approval rate of 58.2% in the intervention group versus 19.4% in the control group. The authors concluded that it is possible to enhance students' critical thinking skills by implementing an educational intervention grounded in the key concepts of Informed Health Decisions [29].

A meta-analysis pooled studies in high school students. The intervention, based on key concepts, increased critical thinking test scores by 33% in students and 32% in teachers. However, 42% of the students in the intervention group did not achieve passing scores, indicating a need for additional reinforcement. Factors such as the use of projectors, prior performance, and gender influenced the results [25].

Teaching key concepts in Spanish

The results of interventions conducted by the Informed Health Decisions team in Uganda have been promising, particularly in terms of applying interventions that teach key concepts to enhance the ability to evaluate health treatment claims. However, these studies have been conducted in specific populations and socioeconomic contexts [20,21,22,23,24,25], so the applicability of their results is limited.

Faced with this situation, several groups have adapted the Informed Health Decisions resources to their specific context [30,31,32,33,34,35,36]. The primary activities of this contextualization are to translate the Informed Health Decisions resources and to pilot-test the material in primary schools. We have also sought to translate and validate the questionnaire to assess the ability to discern the reliability of treatment statements.

In the case of Spanish-speaking countries, to date, there is an official translation of the key concepts of Informed Health Decisions published in 2018 [19]. In the same year, a questionnaire was validated in Mexico to measure the ability to evaluate treatment statements. The instrument is composed of 18 multiple-choice questions that can be used in Spanish-speaking countries for validity and applicability studies in other regions. They can also be used for cross-sectional studies to assess the ability of the general population, children and adults, to analyze treatment claims [34].

There is an experience in Brazil that contextualizes, translates, and validates the didactic resources for key concepts of Informed Health Decisions among elementary school children aged 11 to 12 years [35].

Regarding the Informed Health Decisions resources, the working group of this initiative in Barcelona translated them into Spanish. These resources were pilot-tested in primary schools in Barcelona. In this process, it was concluded that the resources yielded positive results for teaching key concepts related to evaluating treatment claims, although they should be adapted to promote student participation [36].

Strengths, limitations, and future challenges of key concepts

The development of key concepts and their implementation constitutes an organized, multidisciplinary, and systematized response to address infodemia and low health literacy. It has been developed based on existing tools for improving health literacy. In this way, it has managed to improve in aspects such as orderly presentation and the use of simple language that facilitates the creation of resources from it, as well as to establish a multidisciplinary and systematic approach to constant updating [14,15,16,19]. Interventions carried out with primary and secondary school students and their parents have shown promising results in terms of generating critical thinking related to health treatment claims [20,21,22,23,24].

Despite the favorable results in the studied populations, there are limitations, primarily in the implementation of key concepts. These limitations are due to logistical aspects that hinder the implementation of interventions and the heterogeneity in the results presented.

The application of key concepts as an educational resource has been primarily implemented in African countries, which have been open from the outset to incorporate the intervention of Informed Health Choices research into their established school programs [37,38]. It should be considered that no area or context is entirely safe from the dangers of misinformation [5]. Shared decision-making, from the generation of public policies to clinical practice, was contaminated during the COVID-19 pandemic by the spread of false news, but also by scientific production and its consequent translation of knowledge lacking rigor and methodological quality, as happened with drugs such as ivermectin [39]. In this sense, promoting critical thinking in communities should be highlighted as a matter of interest for global public health. Everything points to the need to conduct research in different populations, geographic areas, and contexts to determine the effectiveness of resources that utilize this tool in evaluating claims about health interventions.

On the other hand, access to these resources without the intervention of the Informed Health Decisions group is mainly through the Internet or smart electronic devices. This creates a technological barrier, depending on the context and its circumstances, although attempts have been made to mitigate it by developing resources that do not require an internet connection [34]. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the need to adapt to digital platforms for the provision of educational information has accelerated, which may, in the future, help make interventions more effective [36]. Another limitation is that many instruments developed to assess people’s critical thinking skills rely on self-reports and subjective measurements [13,17].

Despite the results already presented, the heterogeneity of outcome reports and the risk of bias in some investigations that have incorporated the study of key concepts still make it difficult to draw solid conclusions about effectiveness and to determine which intervention method is the most appropriate [40]. Hence, the need for further validations, material adaptations, and pilots in more heterogeneous populations arises. This will enable a more robust body of evidence to be generated, allowing for definitive conclusions to be drawn not only about the effectiveness but also the efficacy of performing this type of intervention. It will then be possible to determine whether it is the right tool to work on health literacy in a comprehensive and integrated manner.

Conclusions

The current scenario of information availability, ranging from varying degrees of reliability, on health treatments has created a need to generate tools that address misinformation and improve health literacy.

The key concepts of Informed Health Decisions constitute a conceptual framework that has enabled the systematic creation of resources and tools to improve and measure the level of health literacy, particularly in evaluating treatment claims. These concepts distinguish themselves from previous tools and guidelines by serving as a basis for addressing their shortcomings, such as overlapping concepts, the exclusion of patients in their development, and a lack of updates.

Interventions utilizing educational resources based on key concepts have demonstrated positive results regarding health literacy among fifth-grade primary school students and adults in Uganda. While the lack of representation from both developing and developed countries in the key concepts-based Informed Health Decisions interventions has been criticized, this is largely due to the difficulty of integrating the interventions into the classroom without disrupting the regular school schedule and curriculum. The questionnaire has been validated in several languages to measure the skills evaluated in the original studies. Additionally, pilots have been carried out with adaptations of the material to new contexts. It would, therefore, be interesting to see a massification of projects of this type, supervised by the Informed Health Decisions team, to evaluate the results of the interventions based on key health literacy concepts in the short, medium, and long term.

The use of these resources in Latin American countries is still in its early stages, with only the validation of questionnaires and no intervention projects on the part of the Informed Health Decisions team.

Finally, we present an infographic in Figure 2, which summarizes the most relevant aspects of the article.

Infographic summary of concepts presented in this article.