Artículo de revisión

← vista completaPublicado el 12 de noviembre de 2024 | http://doi.org/10.5867/medwave.2024.10.2978

Medicina legal en Chile: la Cenicienta sin príncipe

Forensic and legal medicine in Chile: Cinderella without a prince

Abstract

Forensic medicine is of enormous importance in the functioning of contemporary justice systems worldwide. Therefore, in order to characterize the current state of medicolegal and forensic activity in Chile, a non-systematic review of the biomedical and legal literature on the subject was carried out. An analysis of open sources of information was also incorporated, including the National Registry of Individual Health Care Providers, the latest public accounts of the Forensic Medical Service, relevant background information available on the active transparency portal of that institution, exempt resolutions included in the “Chile Law” database (of the Department of Legislative and Documentary Services of the Library of the National Congress) and the lists of judicial experts appointed by the Courts of Appeals of the country for the biennium 2024 to 2025. We note that Chile maintains an unacceptable historical debt in terms of academic development and training of qualified professionals in forensic matters. Likewise, national scientific productivity in this field is practically null. Currently, forensic medicine is the medical specialty with the deepest shortage of professionals nationwide. Consequently, as in the early part of the last century, medical expert opinions are frequently performed by professionals untrained in forensic medicine. This scenario, taking into account the attitudes of certain lawyers and judges (detailed in the article), increases the risk of a miscarriage of justice. National public policies must take urgent action to address the deficits and provide solutions.

Main messages

- Forensic medicine is an essential discipline for the functioning of justice systems.

- Chile has an unacceptable historical debt in terms of academic development and training of qualified professionals in forensic medicine.

- Chile’s contribution to scientific productivity in the field of forensic medicine is practically null.

- The current state of forensic medicine in Chile increases the risk of judicial errors due to a lack of reliability and methodological validity in medical expertise.

Introduction

According to the dictionary of the Real Academia Española de la Lengua, legal medicine is the branch of knowledge in charge of providing expert medical advice to the courts. In Chile, since the promulgation of Supreme Decree 57/2007 [1], it has been recognized by our State as a medical specialty.

The legist is in charge of transcendental tasks for the functioning of justice systems, positioning forensic medicine as a safeguard of the rights of man living in society [2]. Despite its enormous importance, in Chile and neighboring countries it has been characterized as the Cinderella of medicine [3,4]. A discipline that has not been valued as it deserves, has been relegated and even mistreated.

The present work seeks to show synthetically the evolution and current state of the specialty in the country, identifying various deficiencies and suggesting concrete measures to overcome them.

Methods

During April 2024, a non-systematic literature review was carried out, which included a search in medical databases (MEDLINE/PubMed; Virtual Health Library, VHL), a selective check of biomedical and legal literature on the topic and an Internet search using a broad-spectrum search engine (Google). An analysis of open sources of information was also conducted, including the National Registry of Individual Health Care Providers, the latest public accounts of the Chilean Forensic Medical Service, relevant background information available on the active transparency portal of that institution, Exempt Resolutions compiled in the “Chile Law” database (of the Legislative and Documentary Services Department of the Library of the National Congress) and the lists of judicial experts appointed by the Courts of Appeals for the 2024 to 2025 biennium. Finally, regarding ethical aspects, it should be noted that this research is exempt from evaluation by the institutional ethics committee since it is a study on secondary sources of data.

Results

Brief history of forensic medicine in Chile

After gaining independence from Spain in 1818, in 1825, one of the first republican governments prohibited the burial of “those murdered without prior medical examination and the necessary faith of their wounds”. This task was done at the prison yard and even in the police pens [5]. But there were only seven native physicians trained at the Royal University of San Felipe, an entity that in 1809 had closed medical education due to lack of students [4].

In 1833, medical teaching began again. Ten years later, the nascent Universidad de Chile took over this training. The degree lasted six years and only three professors taught all the subjects, including Forensic Medicine in the fifth year. The first teacher in charge was William Blest Cunningham, an Irish physician graduated from the University of Edinburgh, who taught it until 1851 [4].

At the beginning of the 1880s, there were between 350 and 400 physicians in Chile. In this context, in 1887 a regulation was issued by which the so-called "city physicians" were entrusted with the mission of “informing the judicial authority about any medicolegal matter in which their opinion is requested, and having to carry out the examinations and autopsies that may be necessary; to inform the administrative authority about the mental state of persons detained... to verify the deaths of the persons indicated to them, both by the administrative and judicial authorities...” [4]. The expert services that the State received from these physicians were not paid until a judicial sentence was issued [6].

In 1898 the first morgue was inaugurated in Santiago. Three years later, Dr. Carlos Ibar de la Sierra was appointed professor of forensic medicine at the Universidad de Chile. This physician, who had completed his studies in Germany, visionarily identified the need to build a Forensic Medical Institute where all the theory studied in the classrooms could be put into practice and, in addition, contribute effectively to justice. The latter because, with few exceptions, medicolegal expert opinions were performed by unemployed and untrained physicians. Hence, this task was addressed, leading to the creation of the Forensic Medical Service in August 1915, the regulation of its functions by Decree Law 646/1925 and the inauguration of the institutional building in 1926 [4,7,8].

But Dr. Ibar’s commendable effort was soon cut short. In 1928 he was asked to resign without giving any reason. Even worse: in 1930 Decree 2175 was promulgated by which the Forensic Medical Service ceased to belong to the Universidad de Chile and became part of the Ministry of Justice [9]. The teaching of forensic medicine was left as a secondary task of the agency. Thus, the prevailing German model of providing forensic services was abandoned forever.

Medical expertise continued to be performed by “ad hoc” experts. The old Code of Criminal Procedure (1906) and Law 18 355 (still in force) enshrined the custom that general practitioners (often recent graduates) were obliged to take on forensic work. Many medicolegal autopsies were performed in hospitals or (even) in municipal cemeteries by professionals who did not have the necessary knowledge and experience [4].

It was not until 1997, at the initiative of Dr. Alberto Teke Schlicht, that the Universidad de Chile began to offer the first training program for forensic medicine specialists.

In 2000, the new criminal procedure system began to operate, introducing an accusatory model [10]. This change generated significant transformations in evidentiary practices. Without structural or financial adjustments, the Forensic Medical Service was forced to assume an even more preponderant forensic role. In this scenario, it was considered appropriate for the institution itself to grant specialty certificates to its officials. However, in 2003 the Comptroller General of the Republic issued resolution 40065/02, determining that such conduct contravened the legal framework. Moreover, it demanded the return of all certificates that had been issued.

Shortly after, the lack of academic preparation of some Forensic Medical Service experts became evident after the discovery that errors had been made in the identification of bodies of people who disappeared during the Pinochet's dictatorship. This undermined the trust in the work of the agency [4]. However, the episode allowed the Forensic Medical Service to increase budgets and personnel, improve infrastructure, create new offices, develop accreditation and certification programs, among other advances [8].

In 2018 the historic Department of Forensic Medicine of the Universidad de Chile ceased to exist, merging with the Department of Anatomy. That same year, in the city of Temuco, the Universidad de La Frontera began to train specialists in forensic medicine. Thus, only two campuses currently have postgraduate education in the area. These are high-cost programs that must be financed by the physicians themselves or by the State through existing competitions [11]. However, the latter option is contemplated only for some of the few vacancies offered annually.

Current status

The majority of medicolegal procedures in Chile are carried out by officials of the Forensic Medical Service. A small proportion is carried out by physicians hired by the police. In addition, physicians with five years of experience can apply to lists drawn up by the Courts of Appeals and be appointed as experts in civil (not criminal) proceedings. Any physician may also perform forensic tasks privately. Only officials of the Forensic Medical Service are excluded from this possibility because (according to Law 18 575) their special public duty is incompatible with performing medicolegal activities in the private sphere.

Besides a few exceptions in remote areas, healthcare centers do not have forensic medicine units nor hired forensic specialists. This is despite the fact that many forensic activities are performed daily in these facilities.

Unlike recommended standards in other countries [12], in Chile there is no routine medicolegal inspection of corpses prior to cremation. It is also uncommon for a specialist in forensic medicine to work at the crime scenes, while the care of detainees in custody is rarely performed by officials from the Forensic Medical Service.

Today, the Forensic Medical Service has a network of 43 offices. One in each regional capital and the rest in the provinces. According to data from the transparency portal, in February 2024 the number of physicians employed by the institution was 151. More than half (51.7%) have a part-time contract. 47% are listed as “double specialty experts”, which means that they perform dual functions both in the field of forensic pathology and also clinical forensic examinations. The salary gap is significant, with salaries ranging from 2 275 to 9 445 USD per month (for a full-time position), with a median of ± 5 150 USD per month.

In terms of productivity and excluding the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic (years 2020 and 2021), the Forensic Medical Service issues an average of approximately 34 831 medical expert reports per year. Of these, 34.2% are medicolegal autopsies, 41.5% are injury expert reports, 15.4% are sexual assault assessments, 3.9% are histopathological reports and the remainder are psychiatric expert reports (Table 1).

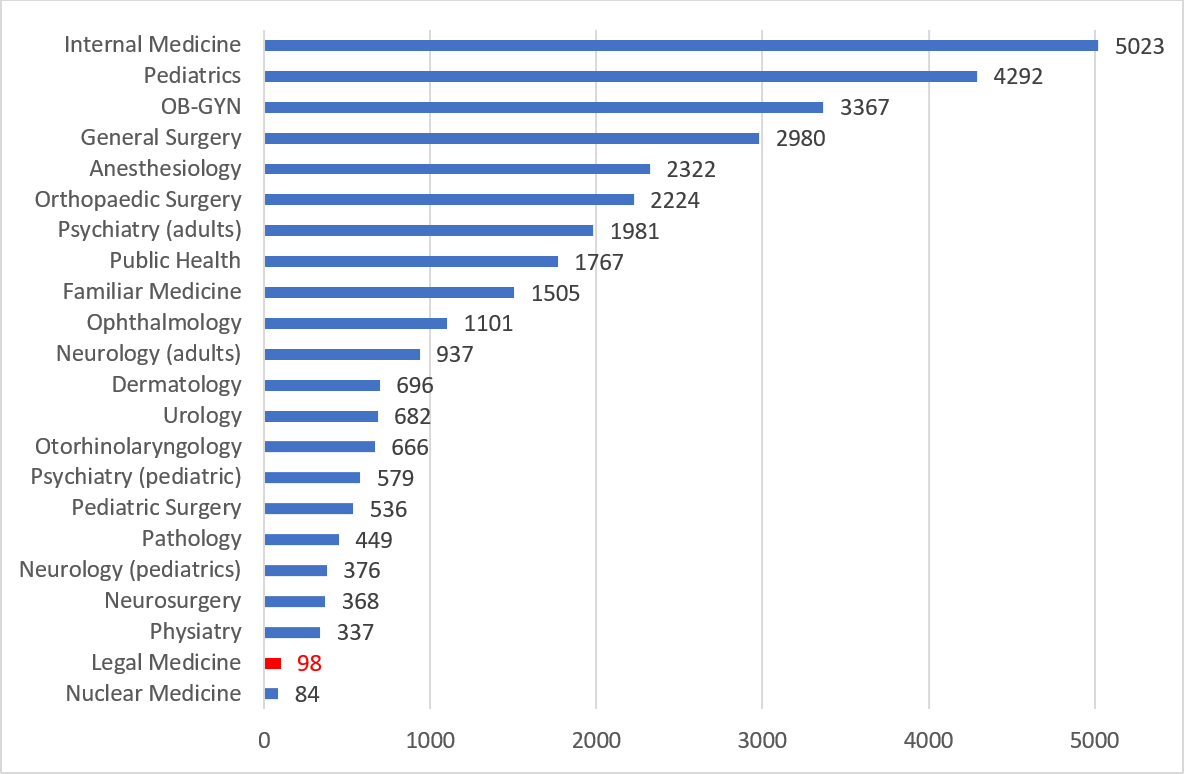

Regarding the number of forensic specialists, data from April 2024 place the specialty as one of the most deficient nationwide (Figure 1).

However, the reality is even worse than what is shown in Figure 1. Of the 98 specialists, one is misclassified because (s)he was trained at a university that has never taught forensic medicine at the postgraduate level. In addition, 52 of the physicians were certified without having completed any postgraduate program in the area, nor having taken an exam to certify their competencies. This was possible after the enactment of Decree 54/2011 [13], which established a transitory modality for the certification of Forensic Medical Service officials with more than five years of permanence in the institution. However, that mechanism contemplated certain requirements indicated in Exempt Decree 31/2013 [14]. It is not possible to corroborate that these physicians complied with such requirements, although it seems quite obvious that many did not [4]. For example, officials who worked exclusively as “forensic psychiatrist” were certified even though they had to demonstrate that they were able to “perform medicolegal expertise in the different areas of the Legal medicine: forensic pathology, clinical forensic medicine, forensic laboratory and criminalistics”.

Number of medical specialists in Chile as of April 20241.

Source: Prepared by the authors based on data published in the National Registry of Individual Health Providers. Available at:

Thus, it is possible to infer that in April 2024 the actual number of specialists in the area does not exceed 45 physicians. This means that forensic medicine is the medical specialty with the greatest shortage of professionals at the national level.

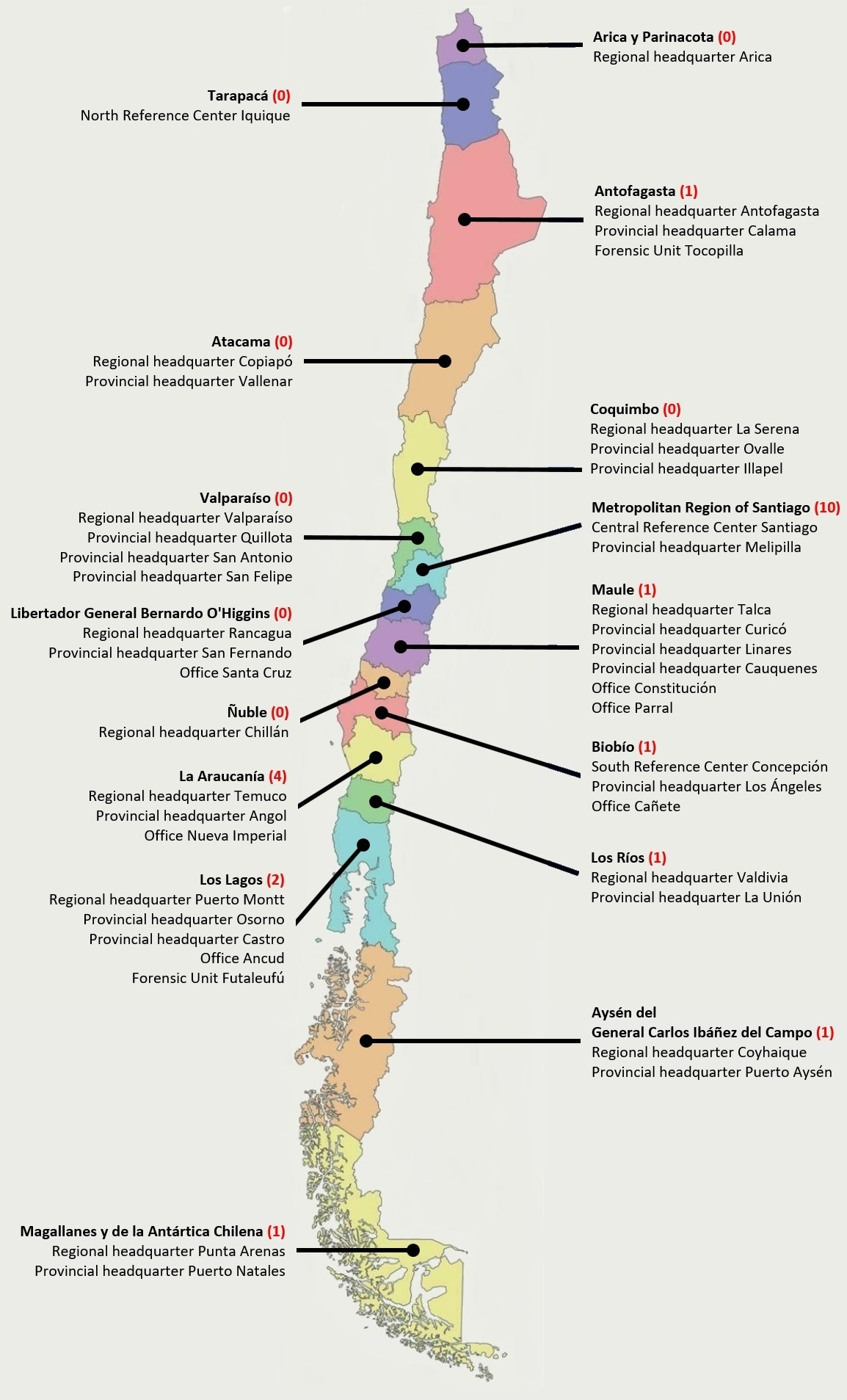

If we analyze how many of those 45 specialists were employed by the Forensic Medical Service in February 2024, we observe that:

-

Only 22 were working at the institution

-

Only 11 work full-time

-

Only 9 of the 16 regions of the country had at least one specialist (Figure 2).

Number and distribution of specialists in Forensic Medicine hired by the Forensic Medical Service as of February 20241.

Source: Prepared by the authors based on data contained in the active transparency portal of the Forensic Medical Service. Available at:

The shortages are similar in the lists of the Courts of Appeals that contain the experts who provide expert opinions in non-criminal matters. For the current biennium 2024 to 2025, the number of physicians registered nationwide reaches 93. Only five of them (5.4%) are specialists in forensic medicine. There is also a certain disorder in the preparation of the registry. For example, one of the professionals accepted to provide forensic medicine expertise does not even have a medical degree.

Finally, it should be noted that Chile’s contribution to scientific productivity in the field of forensic medicine is almost null, as shown by recent research on the subject [15].

Discussion

It is indisputable that the Forensic Medical Service has made notable progress in the last 15 years. Territorial coverage has been increased by building or setting up new offices. A great effort has been made to improve the infrastructure, providing the facilities with modern, spacious, more comfortable and safer architectural standards. In terms of technology, there have been significant improvements following the acquisition of multiple and diverse pieces of equipment, many of which are last generation one’s. This has allowed, among other things, certain laboratory and forensic genetics processes to be standardized, accredited and certified under ISO 17 025 standard. In addition, several technical guidelines have been issued that set the minimum requirements for the performance of forensic tasks (Table 2). This is in addition to the use of other instruments endorsed worldwide, such as the Istanbul Protocol, the Minnesota Protocol and the Latin American Protocol for the Investigation of Gender-Related Violent Deaths of Women.

However, in the academic field and in terms of training of qualified professionals, Chile maintains an unacceptable historical debt. As was the case in Dr. Ibar’s time, very often medical expert reports are still performed by professionals who are not specialized in forensic medicine.

This problem is not a mere question of labels. Nerio Rojas from Argentina pointed out: “Some have said that it is enough to be a well-informed physician to be a good forensic doctor. A crass and dangerous mistake... Legal medicine requires special knowledges, it has its own matters... it requires a lot of legal and juridical knowledge that most physicians are ignorant of or misunderstand; it demands own mental habits and a certain special criterion, alien to ordinary medicine, which ones can only be given by postgraduate studies..." [16].

More than a century ago, the Frenchman Alphonse Bertillon told us “you only see what you look at and you only look at what you have in mind”. So, to pretend that a physician who has not studied the specialty is qualified to perform forensic activities is nonsense [4]. Forensic medicine is not a by-product of other disciplines. It requires sufficient training to develop the necessary competencies for proper performance [17]. Thus, the practice of appointing any physician as an expert witness is wrong in every sense and deprives the accused, the complainant and society in general of guarantees [4,16]. National and comparative experience is replete with cases that show that the lack qualified experts is a factor that increases the probability of error in the criminal justice system, including the conviction of innocent people [18].

We know that the training in forensic medicine given at the undergraduate level is insufficient [19,20]. It is also a fact that, despite being a need recognized by other authors [21], in Chile there are very few forensic medicine modules in training programs for specialists in other areas of medicine. However, it is not uncommon for some to believe that the physician’s experience or the existence of technical standards are sufficient tools to overcome those deficiencies in academic training. However, reality proves otherwise.

Experience does not guarantee the use of reliable knowledge. An expert witness may have very little experience, but still know what he is talking about; another very experienced, may not. Or vice versa. Or maybe they both know. Or perhaps, neither... What is certain is that a physician practicing as an expert witness, guided only by his experience, skills and clinical intuition, will sooner or later systematically establish conclusions that are scientifically obsolete or out of line from the legal framework. Besides that, audits have shown that Forensic Medical Service officials were not even aware of the existence of standards published by the institution [22]. Furthermore, the protocols are not cooking recipes. Their correct application requires the physician to be versed in forensic medicine and to understand that expert job implies a way of acting and thinking that is different from what is expected of a professional who is not performing this role [23]. In this logic, the Spaniard Romero states: “The medicolegal method is, certainly, something proper to our science, to which it gives its specific physiognomy. For this reason, their ignorance... determines that an eminent clinician, a competent specialist in own field, is in practice a very mediocre expert witness” [2].

It is common then that novice physicians in forensic tasks adhere to the culture of “learning by doing”. And in institutions such as the Forensic Medical Service or the police, the saying “wherever you go, do what you see” is often followed. This favors both the transmission and perpetuation over time of bad practices and vintage knowledge [24,25,26]. Thus, concepts continue to be repeated without rigorous scientific evaluation [26,27]. All this has detrimental consequences for forensic activity and ultimately harmful for society, since it affects the quality of the decisions that the judicial system adopts by considering questionable expert´s advice.

Unfortunately, the Chilean State continue to avoid the aforementioned problems. Deficits are made up and masked by granting degrees and certifications. Improvised solutions are maintained and we see with impotence that they continue to opt for training recent graduates physicians to perform delicate forensic tasks. An example of this is an announcement made by the surrogate National Director of the Forensic Medical Service in the public account of 2020: “... to capacitate phisicians from Porvenir and Tierra del Fuego in basic thanatological skills, which allow them to solve autopsies of little technical difficulty and provide coverage in cases that do not require a detailed thanatological study” [28]. Beyond the fact that there are no “autopsies of little technical difficulty” (all of them, however simple they may seem, have associated complexities), the question is: would anyone undergo cardiac surgery performed by a general practitioner or a gynecologist? The answer seems obvious: no one. So why does our system allow a medicolegal autopsy (and other types of forensic expertise as well) to be performed by any physician?

Considering the background that has been exposed, one would expect the actors of the justice system (especially prosecutors and criminal judges) to react. Curiously, beyond poorly qualifying the reliability and methodological validity of the expert reports ventilated in criminal proceedings [29], they continue to admit them without further debate [30]. “A culture has been installed in the system according to which this evidence should not be subject to very strict scrutiny” [31]. Such behavior is not trivial. There is full consensus that (during the development of the trial), litigation is not a sufficient or efficient tool to avoid errors related to expert witness evidence. Therefore, in agreement with what has been reported in Chile [31] and other countries [32,33], there are clear limitations or (at least) skepticism about the effectiveness of the system to exclude erroneous medical expert reports.

The serious thing about the matter, is that excessive weight is often given to this evidence without adequate justification [34]. When determining the facts of a criminal case, 92% of lawyers and 83% of judges consider the expert report to be relevant or very relevant. And if we analyze other areas of law, these percentages do not fall below 82% [29]. Moreover, as in other parts of the world [35], judges are biased in favor of evidence from the Public Prosecutor’s Office and experts from “official” auxiliary agencies such as the Forensic Medical Service [34]. Thus, a rather dangerous scenario is configured: the greater the impact of the evidence, coupled with less control, results in a greater probability of error.

The current priority must be to increase the number of specialists and their quality, in order to give the discipline the status it deserves. This is necessary for the proper functioning of the justice system. Undergraduate forensic medicine courses must be improved and these studies must be promoted as a legitimate medical and academic career. On the other hand, the Forensic Medical Service can arrange for all physicians hired without the specialty of forensic medicine (both current and future) to certify their knowledge at the National Autonomous Corporation for the Certification of Medical Specialties. It is only necessary to allocate resources (much less than those required for postgraduate training) and coordinate with the specialty committee, so that the evaluation ensures that the physician who passes will have the minimum competencies required to perform adequately as an official of the Forensic Medical Service.

Universities must create new training centers for specialists in forensic medicine and increase the existing quotas, incorporating some of their subjects to all medical specialization programs. The Forensic Medical Service can achieve this objective by adapting the agreements it has with academic entities. However, this postgraduate education entails expenses that must be covered [36]. This is where the State (through the Ministry of Justice and Human Rights) has to act, a matter that has been expressed for almost 20 years now [20]. In the same way that the Ministry of Health has managed a progressive and annual budget expansion for these purposes [11], the Ministry of Justice must begin to contemplate similar actions. And true, this may require legal modifications. But while waiting for something like this to materialize, all the other public agencies directly or indirectly involved in the issue (e.g., the Judiciary, Ministry of the Interior and Public Security, Public Prosecutor’s Office, Public Defender’s Office, etc.), could recognize the relevance of the matter and allocate resources to the task. An alternative that, in our opinion, the Ministry of Finance can and should contemplate in the next public sector budget laws.

A public policy aimed at strengthening forensic medicine in Chile should move forward, seeking to prioritize this subject in the professional training and research programs of the National Agency for Research and Development [31].

Finally, only when a critical mass of new specialists in forensic medicine has been formed, it would be good to consider the creation of forensic units in the most complex hospitals. This is justified, among others, by the fact that the medicolegal activities performed in these facilities are not always carried out correctly [19,37,38,39,40].

Conclusions

“The attention a country pays to forensic medicine is an exponent of social maturity, an index of civility...”. Under that paradigm we are in a bad way. Chile maintains an unacceptable historical debt in terms of academic development and training of suitable professionals in forensic medicine. Moreover, lawyers and judges are deeply involved in the unsatisfactory development of the specialty, as they are satisfied with expert witness reports issued by any physician. The State must take charge of the deficits and progressively manage the solutions with public policies that attack the problems identified. No more inertia, complacency and improvisation: all the actors in the system must level upwards. Cinderella needs her princes.