Reporte de caso

← vista completaPublicado el 28 de marzo de 2022 | http://doi.org/10.5867/medwave.2022.02.002519

Transformación nodular angiomatoide esclerosante del bazo: reporte de caso

Sclerosing angiomatoid nodular transformation of the spleen: A case report

Abstract

Sclerosing angiomatoid nodular transformation is a benign vascular pathology of the spleen, developed from the red pulp, of unknown etiology; it is postulated that it may be related to IgG4 disease and Epstein-Barr virus infection. Most cases are asymptomatic, constituting incidental findings in imaging studies. We present a 41-year-old male patient with a history of thyroidectomy for papillary carcinoma who consulted for fever, received symptomatic treatment and performed a computed tomography of the abdomen for nonspecific abdominal symptoms, the same evidence in the lower pole of the spleen a solid-looking image with faint Peripheral enhancement with contrast, measures 62x 52x51 mm. A splenectomy measuring 14x 11x4 cm and weighing 284 grams was performed, identifying a solid, well-defined nodular formation, with a central fibrous-looking area, with whitish tracts that delimited purplish areas. Microscopy: rounded angiomatoid-like coalescing nodules, with vascular proliferation lined by endothelial cells without atypia, interspersed with spindle cells, infiltrated by lymphocytes and macrophages. The stroma between the nodules shows myofibroblastic proliferation with lymphocytes, plasma cells, and siderophages. Immunohistochemistry: positive labeling in vessels for CD34 and CD31, positive sectors for CD8 and negative for CD34. One IgG4 positive cell per high power field. The study for Epstein-Barr by Polymesara Chain Reaction was negative. For the diagnosis, the imaging studies are nonspecific, so the diagnostic confirmation is given by the histopathological study. Splenectomy is curative with no reported cases of malignant transformation or recurrence to date. There are no known risk factors and no triggering factors have been proven, except the association of cases with IgG4 and Ebstein-Barr virus. As it is a recently described pathological entity, it is necessary to collect large series and review our files, reevaluating some of its differential diagnoses to achieve a better understanding of it

|

Main messages

|

Introduction

Sclerosing angiomatoid nodular transformation, first described by Martel et al. in 2004 [1], is rare. The existing evidence is based predominantly on less than 150 case reports [2], many of which focus on radiological images [3]. These lesions are usually solitary, but about six multifocal cases have been reported [4].

This lesion is a benign vascular pathology of the spleen, developed from the red pulp. The etiopathogenesis is unknown, although it is suggested that it may be related to immunoglobulin four (IgG4) disease [1]. Diagnostic criteria for IgG4 diseaserelated sclerosing angiomatoid nodular transformation consists of the presence of a mass, nodular lesion or organ dysfunction, serum IgG4 concentration greater than 135 micrograms per deciliter (reference value between one and 135 micrograms per deciliter), more than 10 IgG4-positive cells per highmagnification field, and an IgG4/IgG ratio greater than 0.4 [5]. Another likely cause is Epstein-Barr virus infection, and some isolated cases are associated with Mafucci syndrome [6]. Most cases are asymptomatic and present as incidental findings in radiological studies [7].

Case Report

A 41-year-old male patient (engineer by profession) consulted in 2018 for a non-specific febrile syndrome. He received symptomatic treatment for intermittent non-specific abdominal symptoms. As he continued with symptomatology, physicians in charge decided to perform an abdominal computed tomography. He had a history of hypothyroidism treated with levothyroxine 175 micrograms per day due to thyroidectomy for a classic variant papillary carcinoma in the right lobe and papillary microcarcinoma in the left lobe. He had surgical treatment in 2015 and later received radioactive iodine.

On physical examination, he had a blood pressure of 140/80 millimeters of mercury, a heart rate of 68 beats per minute, a respiratory rate of 15 breaths per minute, and a temperature of 37.3 degrees Celsius. In addition, he had cervical lymphedema linked to previous surgery (total thyroidectomy and cervical lymphadenectomy) and pain on palpation in the right flank, without peritoneal reaction. Laboratory tests revealed 4 960 000 red blood cells per cubic millimeters, 13 880 leukocytes per cubic millimeters (neutrophils 85%), hemoglobin of 14.5 grams per deciliter, hematocrit of 42.1%, 246 000 platelets per cubic millimeters, urea 30.6 micrograms per deciliter, creatinine 0.90 micrograms per deciliter, total bilirubin 0.6 micrograms per deciliter, aspartate aminotransferase 19.5 international units per liter, alanine aminotransferase 23.3 international units per liter and erythrocyte sedimentation rate 7 millimeters per hour. Serology for hydatidosis, HIV 1 and 2, hepatitis B virus, and hepatitis C were negative. The electrocardiogram was normal.

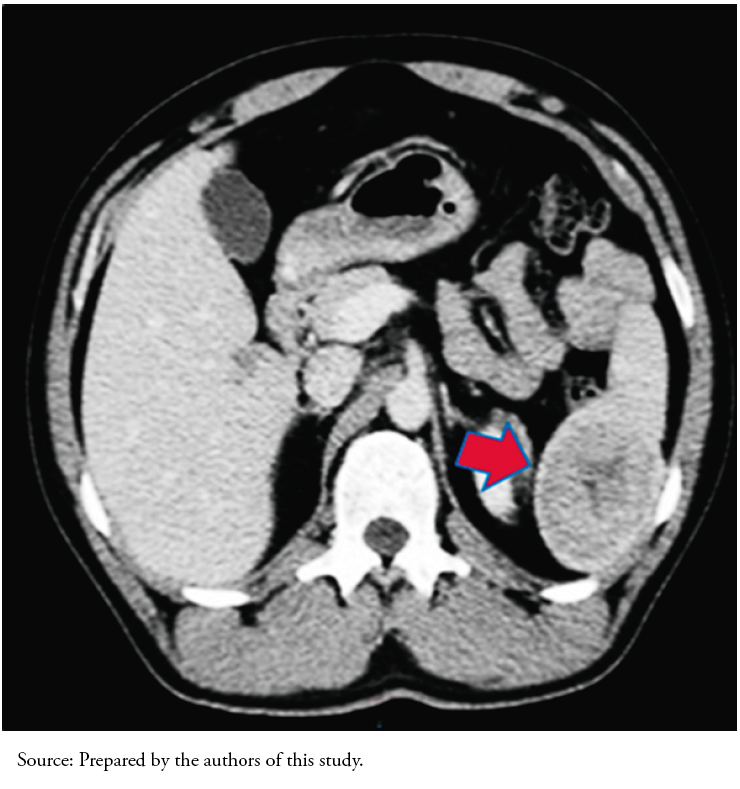

Abdominal computed tomography findings showed an abnormal image of the spleen. Given this finding, a consultation with oncology and a contrasted abdominal and pelvic computed tomography were indicated (Figure 1). The new image showed a solid lesion at the lower pole of the spleen measuring 62 by 52 by 51 millimeters with a hypodense center that slightly enhanced peripherally with contrast.

The risk of malignancy encouraged a splenectomy with a laparoscopic approach. Before surgery, the patient received vaccination against influenza, pneumococcus, meningococcus, and Haemophilus influenzae.

In the macroscopic study, the organ measured 14 by 11 by 4 centimeters and weighed 284 grams. A solid nodular formation was observed at the subcapsular level in the lower pole. This mass was well-circumscribed, with a central whitish area of fibrous aspect and whitish tracts defining violaceous areas measuring 4.5 by 4 centimeters (Figure 2).

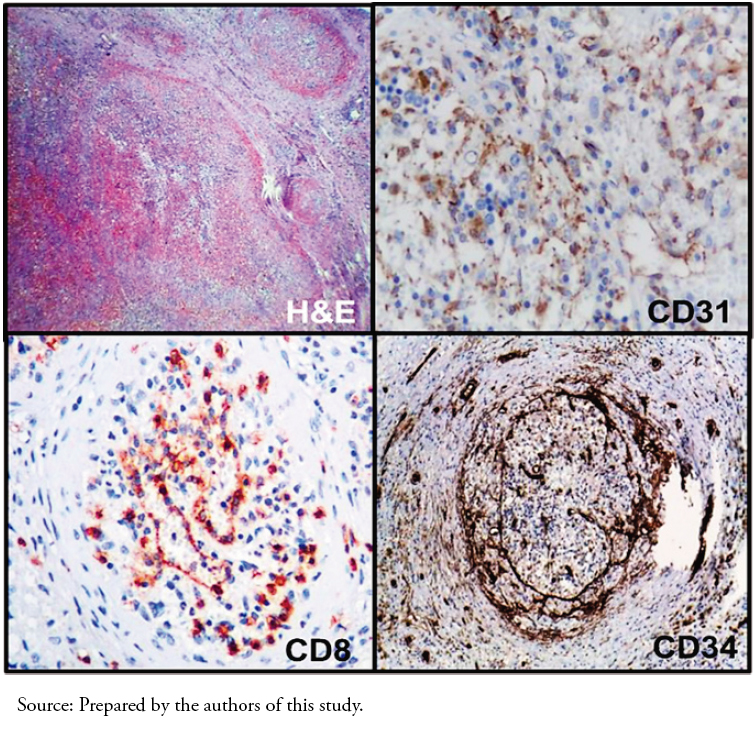

Microscopic findings showed round coalescent nodules of angiomatoid appearance, in which a slit-like vascular proliferation was lined by endothelial cells without atypia. The vessels were interspersed with spindle cells and inflammatory cells, including lymphocytes and macrophages. The stroma surrounding the nodules was myxoid, and some sectors were fibrous, with a myofibroblastic proliferation accompanied by lymphocytes, plasmacytes, and siderophages. Regarding immunohistochemistry, the vessels were positive for CD34 and CD31, and some areas were positive for CD8 and negative for CD34 (Figure 3). The number of IgG4-positive cells was one per high magnification field, and the IgG4/IgG ratio was less than 0.4. The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test for EpsteinBarr virus was negative.

The patient evolved favorably after surgery with no surgical or infectious complications to date and remained on the usual medication without requiring adjuvant treatment. Post-surgical laboratory studies showed 4 535 000 red blood cells per cubic millimeters, 7600 leukocytes per cubic millimeters (neutrophils 72%), hemoglobin of 13.2 grams per deciliter, hematocrit of 41%, 301 000 platelets per cubic millimeters, aspartate aminotransferase 17 international units per liter, and alanine aminotransferase 18.5 international units per liter.

Full size

Full size  Full size

Full size  Full size

Full size Discussion

Sclerosing angiomatoid nodular transformation is a rare benign pathology with a slight female predominance that usually appears between 22 and 74 years of age (mean age: 50 years). They are asymptomatic lesions that usually appear as incidental findings on imaging studies.

These lesions are solitary masses that can measure from 0.9 to 17 centimeters. Radiologic features are non-specific, and histopathologic study is the gold standard for diagnosis. Macroscopically, they are well delimited non-encapsulated nodular lesions that present a central fibrous scar-like area, from which tracts radiate delimiting pseudo-nodules. The histological study is characterized by angiomatoid coalescing nodules composed of capillaries, venules, and sinusoids, divided by fibroconnective tracts. The internodular stroma consists of dense fibrous tissue with areas of myxoid appearance, scattered myofibroblasts, plasma cells, lymphocytes, and hemosiderophages.

Although the histologic image is distinctive, it is necessary to rule out more frequent pathologies. Immunohistochemistry is very useful, since these lesions have a distinctive immunophenotypic pattern characterized by CD34 (-) CD31 (+) CD8 (+) in the sinusoids, CD34 (+) CD31 (+) CD8 (-) in the capillaries and CD34 (-) CD31 (+) CD8 (-) in small veins. CD68 is positive in macrophages, and some cells are CD68 (+) and SMA (+) [8],[9]. Some cases reported CD30 (+), others had Epstein-Barr virus expression by in situ hybridization (Epstein-B virusencoded small RNA, EBER), and some were negative for both [10],[11].

The proliferation rate with Ki67 is low (approximately less than 4%). The etiopathogenesis of proliferation seen in sclerosing angiomatoid nodular transformations may be related to the sclerosing lesions of IgG4 disease since fibroconnective stroma have increased IgG4-positive plasma cells. In our case, the number of IgG4 positive cells was one (measured by high magnification field), and the ratio of IgG4 positive cells to immunoglobulin positive cells was less than 0.4. Therefore, we considered that the lesion is not related to IgG4 disease. The negative marking for the Epstein-Barr virus by PCR would also exclude the association with this virus.

Lymphoid tumors are the most common spleen malignancies, while non-lymphoid tumors are scarcely reported [2],[7] and generally of vascular origin. Although pre-surgical studies may suggest many diseases, once macroscopy and histology are reviewed, the lesions are usually diagnosed as hamartoma, conventional hemangioma, hemangioendothelioma, littoral cell angioma, and carcinoma metastases [7].

Within the nodules, endothelial lining cells are negative for D240, which confirms a vascular instead of a lymphatic origin. Cao et al. reviewed publications in English and found that 30 of 127 cases (23.6%) coexisted with other diseases, including idiopathic myelofibrosis, bile duct and pancreatic cancer, acute pyelonephritis, and malignant tumors [4]. The authors compared these findings with Martel’s original report and concluded that patients with sclerosing angiomatoid nodular transformation have a relatively high prevalence of synchronicity with diseases in other organs. Therefore, clinicians and radiologists should not automatically assume a splenic lesion coexisting with a malignant neoplasm as tumor metastasis and should evaluate differentials such as sclerosing angiomatoid nodular transformation or other – more frequent – pathologies [1],[4].

Splenectomy is curative, with no reported malignant transformation or recurrence cases to date. Some authors propose laparoscopic hemisplenectomy as the treatment of choice instead of open splenectomy. They suggest that the laparoscopic approach shortens hospitalization days, reduces medical expenses, has fewer wound complications, and offers better cosmetic results.

Although sclerosing angiomatoid nodular transformation has relatively specific imaging findings, the differential diagnosis with other benign or malignant splenic tumors is challenging.

This disease is only recently described in the literature (2004). Therefore, it is necessary to collect a more extensive series of cases and reevaluate differential diagnoses of previous cases to understand sclerosing angiomatoid nodular transformation better. As discussed by Agrawal et al. through their own two case reports and review of the literature (one of them associated with extensive extramedullary hematopoiesis), tumors with the characteristic morphology of sclerosing angiomatoid nodular transformation have been reported (at least) since 1978. Many were previously diagnosed as exuberant splenic granulation tissue, hamartomas, multinodular hemangiomas, or even inflammatory pseudotumors. The disease has been reported intermittently, but new cases with even newer associations appear from time to time.

In Ecuador, Fernandez and Lara published in 2018 a case of sclerosing angiomatoid nodular transformation in a 76-year-old patient with a spleen mass. A laparotomy with splenectomy confirmed the diagnosis by microscopy and immunohistochemistry (CD31+, CD34+), presenting similarly to our case [12].

A case of a 72-year-old male patient diagnosed by an ultrasoundguided puncture was also published. The pathologic study showed fibroblast proliferation, lymphocytes and plasma cells infiltration, and areas with small slit-like blood vessels. Immunohistochemistry revealed the presence of CD31 (+) and CD34 (+) cells in small blood vessels [13].

There are no known risk factors, except for the association with IgG4 and Epstein-Barr virus. In the title of a paper, it has been proposed whether sclerosing angiomatoid nodular transformation is "A new entity or a new name?" [14]. Perhaps this latter possibility is the most appropriate point of view.

Conclusion

Sclerosing angiomatoid nodular transformation is a rare and benign pathology, usually diagnosed through incidental findings. Physicians should keep it in mind in the differential diagnosis of spleen tumors.

Notes

Contributor roles

JBCL, LMTC, PCMS, AARC: clinical case data collection, conceptualization, writing-reviewing and editing of the draft and writing-reviewing and editing of the final article.

Acknowledgments

Medical School of the Catholic University of Cuenca, Azogues branch. Homero Castanier Crespo Hospital, Azogues, Ecuador. Hospital IESSBabahoyo, Ecuador. Hbr Health & Behavior Research Group, Cuenca, Ecuador. CIGMHA Research Group, Azogues, Ecuador. Vice Rectorate for Research and Innovation, Society Outreach and Graduate Studies, Catholic University of Cuenca, Ecuador. Clinical Psychology Career of the Catholic University of Cuenca, Ecuador. Laboratory of Psychometry, Comparative Psychology and Ethology of the Center for Research, Innovation and Technology Transfer (CIITT) of the Catholic University of Cuenca, Ecuador.

Competing interests

The authors completed the ICMJE conflict of interest statement and declared that they received no funding for this article; have no financial relationships with organizations that may have an interest in the published article in the past three years; and have no other relationships or activities that may influence the publication of the article. Forms can be requested by contacting the corresponding author.

Funding

The authors declare no funding.

Ethics

The protocols were followed at the center where the patient data were collected. Authorization was obtained from the Teaching and Research Department of the Homero Castanier Crespo Hospital.

Language of submission

Spanish.